Rugby league revolutionary Warren Ryan opens up on his coaching philosophy

Warren Ryan was so far ahead of the game that the rules were changed to keep pace with him. He opens up to DEAN RITCHIE about his tactics, the infamous 1989 grand final call and why Wayne Bennett can’t teach football.

NRL

Don't miss out on the headlines from NRL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

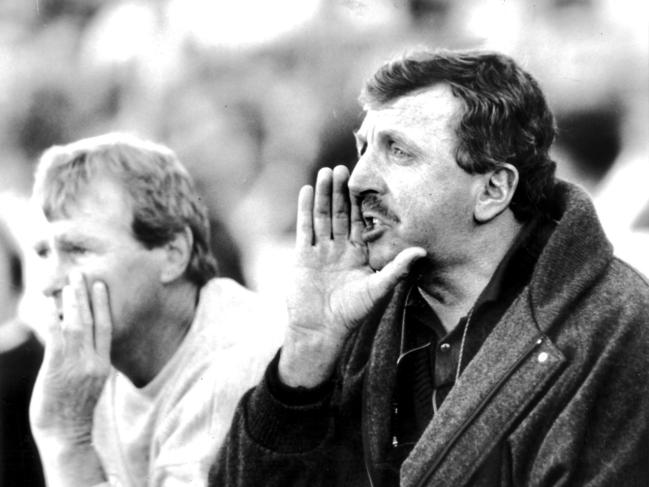

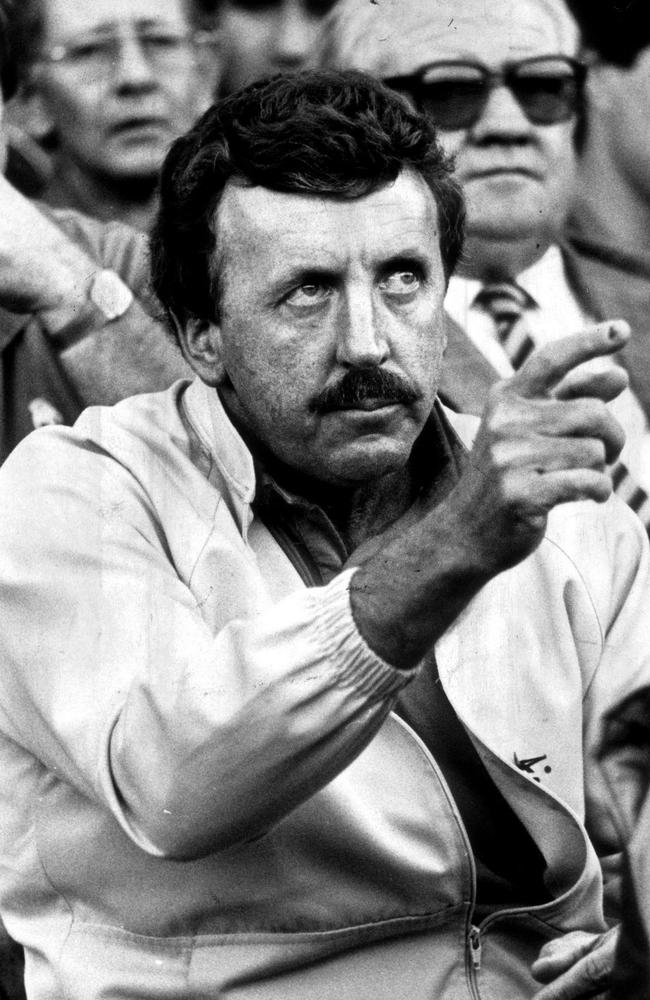

This is the man who became rugby league’s first true on-field coaching innovator, a pioneer who forever changed the game through analytics and science.

While Jack Gibson spearheaded rugby league’s adoption of NFL concepts, Warren Ryan was the revolutionary trailblazer who replaced outdated coaching methods.

Even today, aged 83, Ryan talks about Newton’s law, velocity, maximal strains, feet movement, equalisation on the blind, line theories... even the science of darts.

He was ahead of his time.

In this exclusive interview, Ryan also cleared up some controversies through his remarkable 15-season coaching career, which started with Newtown in 1979, including a dramatic moment during Balmain’s heartbreaking 1989 grand final loss.

Ryan probably wouldn’t survive in today’s politically correct world.

At times abrasive and direct, Ryan would often tell players: “I won’t sugar-coat a bitter pill.” He once told a young player in front of teammates: “There are two things you’re no good at in football – running and tackling.”

No coach had previously broken down a game with such clinical precision through a theory which dissected the field into thirds and tramway grids.

He would tell his players that the jigsaw puzzle would one day make sense.

When Ryan – nicknamed Wok – arrived at Canterbury ahead of the 1984 season, he said: “They didn’t have a clue what they were doing.”

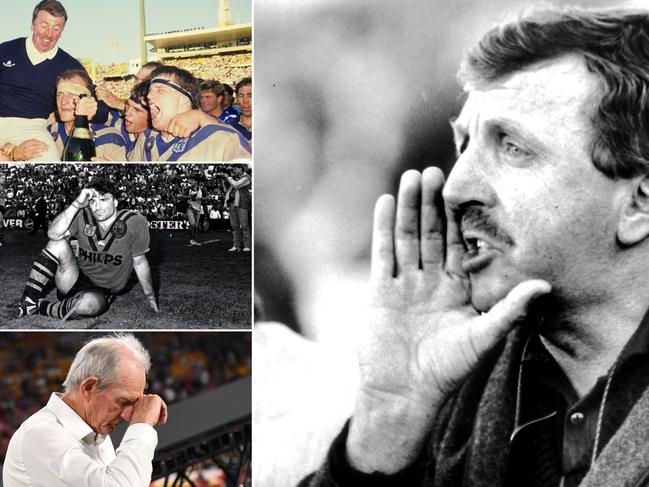

They won the premiership that season.

His meticulous style took him to six grand finals in the ‘80s with three different clubs, winning two, via a ruthless and brutal defensive style.

Ryan even forced two rule changes by the NSWRL.

He was the first coach to split the centres, inside and outside became left and right, have ‘middle’ forwards, while also paying for a camera to film head-on vision of opposition sides to prepare for games.

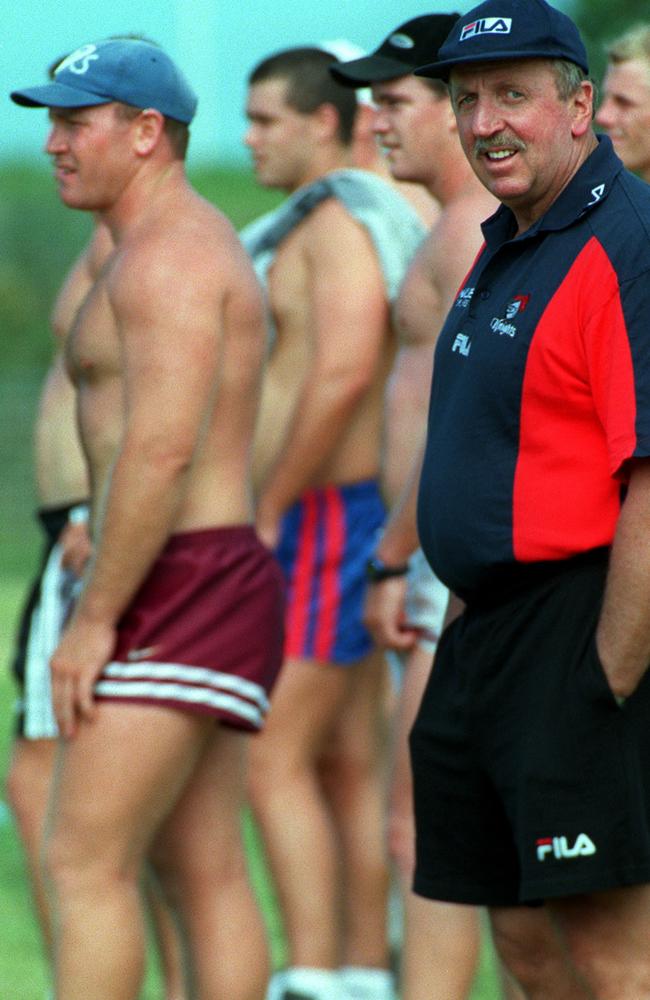

His distinctive moustache now turned a touch grey, Ryan still gets irritated by some issues in the game but was generally relaxed while chatting over a schooner of beer at Hotel Maroubra.

With his long-time mate and former Bulldogs star Paul Langmack sitting alongside him, Ryan shuffled around mobile phones and beer coasters when trying to demonstrate his coaching systems. It was confusing, yet fascinating.

Ryan’s game knowledge and philosophies remain astonishing. Langmack, his ever-loyal lieutenant, often chimed into the interview to further parade Ryan’s craft.

“Warren gave us tomorrow’s knowledge today. He was very analytical – he taught us how to read numbers,” Langmack said.

Ryan added: “The science in rugby league is waiting to greet you if you take the time to look.”

He cleared up why Balmain forwards Steve Roach and Paul Sironen were infamously dragged from the ‘89 grand final while describing Canterbury’s brutal Dogs of War forward pack as “terrifying.”

Ryan also revealed who he thought started the wild 1981 semi-final brawl between his Newtown team and Manly, while taking a veiled dig at fellow coaching legend Wayne Bennett.

After the interview, Ryan headed out to a Chinese restaurant with some mates along with his ex-players Langmack, Andrew Johns, John Dorahy, Paul Dunn and Andrew Farrar.

They are all fiercely loyal to Ryan, knowing how heavily their careers were enhanced and influenced by their former coach, who spent stints at Newtown, Canterbury, Balmain, Wests and Newcastle.

“I’m proud that blokes I taught footy are grateful and that they come and see me. I treasure that,” Ryan said.

BLOCKER AND SIRRO

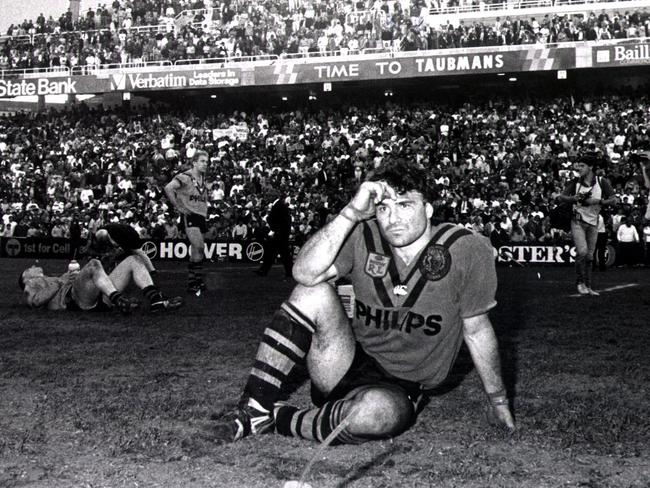

Ryan suffered heartbreak after losing the 1989 grand final to Canberra in extra time.

And it was his decision to take Roach and Sironen from the field late in the game that attracted significant criticism.

“Nobody really examined it. People were critical and your mob (News Corp) said, ‘The coach blew it’. There were agendas,” he said.

“Canberra was running from dummy half. A big forward like ‘Blocker’ (Roach) can get a wind-up speed but reactive speed laterally, he was struggling defensively.

“I was just trying to protect the lead and trying to get over the line to win the game.

“We didn’t look like improving the score, quite frankly.

“You have to do something, so I thought we’d get some blokes out there who were quicker movers to try and cover this dummy half running they were doing.

“It was extremely tough because it was so winnable, particularly with Benny (Elias) hitting the crossbar (through a field-goal attempt).

“I was pretty annoyed with a ruling that day which cost us a try.

“The deeper you go into grand finals, it’s harder to take when you’re beaten, I will say that.

“Benny was a wonderful player, my word he was tough. Gary Freeman (Balmain halfback) wasn’t a ballplayer so I realised I had to push the game forward onto the advantage line.

“So we played the game at Balmain on the advantage line with good, big forwards and Benny was darting in and out and the whole game was pushed forward.

“Freeman was a wonderful support player, was a tough little defender and terrific competitor but he wasn’t creative. Some people are, some aren’t.”

BENNETT BARB

Ryan still enjoys rugby league, but questioned the pure ability of some current coaches.

“I think there are a lot of coaches who have been very fortunate that they’ve had players who have provided skill that they didn’t teach,” he said.

“I know a bloke (Wayne Bennett) who won a lot of comps in Queensland because Kevvie (Walters) and ‘Alfie’ (Langer) supplied the smarts, and tough forwards.

“Wayne’s big thing is to get the best players and keep them happy, not teach them football. It’s a sensible theory if you can’t teach football.

“A lot of them don’t teach football. I remember coaches would ring me because there seemed to be some process where they all shared tips.

“I used to say, ‘Sorry, I don’t want to be part of it – I’m not in the dial-a-prayer club’.

“You hear all these people babble about players running good lines but they wouldn’t know it if their arses were on fire unless the fire brigade arrived.

“A good line is where you strain the lateral movement of the defender to the maximum.”

REVOLUTIONARY RYAN

Read this carefully and learn.

“There is a science in darts and you stand still to play so, as you could imagine, the science in football is enormous. It’s waiting to greet you if you take the time to look,” he said.

“One of the things that facilitates the ability to find the science is seeing a reduced numbers game – 13 on 13 tends to hide the science of the game.

“When you’ve got reduced numbers, you play in the gaps and the subtlety of drawing people.

“You just don’t run in the middle of the hole and offer the chance for both defenders to move laterally.

“You know which defender you want to move and you play to the half of his gap. You run at him first and then gradually move.

“You learn to see the cumulative effect of that as you move one bloke inwards.

“(The second player) plays in the small half of the hole, he maximally strains the other bloke’s movement, the gaps get progressively wider and you create outside room and overlaps.”

It became Ryan’s Euroka moment.

“I invented something called the ‘line theory’,” he said.

“The field would be 100 per cent wide and we’d play to 70. So that would be a three-man short side, seven coming back, two markers and a fullback. There’s your 13.

“Fifty per cent would be down the middle when you’d have five and five, two and one. Forty would be four and six, two and one. You can pick out blokes on the field you can play to.

“I can only conclude that you’re a process of everything that has happened to you up until that point. I was always disappointed in older football – I was only a lower grader at St George – but I didn’t think they put a lot of thought into it.”

Langmack added: “We knew what we were going to do in four tackles before the next play.”

Ryan responded: “I just knew.”

DOGS OF WAR

Canterbury’s famous pack in the mid-1980s was fierce.

Under Ryan’s dour approach, the Dogs of War claimed titles in 1984 and 1985 – the era coming just five years after Canterbury won a grand final under coach Ted Glossop’s team dubbed The Entertainers.

“They (Dogs of War pack) were terrifying, a terrifying brick wall,” Ryan said.

“I remember ‘Turvey’ (Steve Mortimer) saying to me, ‘We were supposed to be The Entertainers, but this mob in front of me, they’re terrifying’.

“They had toughness in them and when they were on a unified course, with their footwork, they knew they were hurtful. David Gillespie hit a bloke that hard one day that you thought the opposition pack were going to break camp and leave.”

In one game, there were fears North Sydney wouldn’t come out of the sheds at halftime.

“You put them in a corner, equalise on the blind, move up quick on the open and there’s no way out,” Ryan recalled.

“They weren’t going to spread the ball across their goal line in the five metre rule.

“I did have the pleasure of stopping Parramatta’s run (in the early 1980s).

“They could have feasibly won six grand finals in a row. I kicked them off with Newtown in ’81 and killed them off in ’84 and ’85 and they beat us in ’86.”

THE BRAWL

Via a try to Tommy Raudonikis, Ryan’s Jets hit the front in the 1981 grand final before an emerging Parramatta side, led by two-try hero Brett Kenny, surged home to win 20-11.

While Newtown’s efforts to make the grand final with a modest roster was meritorious, it was the Jets’ major semi-final win over Manly which will be forever remembered for arguably the wildest brawl rugby league had ever seen.

And Ryan had a fair idea who instigated the fight.

Asked whether he knew a fight was going to explode, Ryan said: “No, not really, no, but I suspected. You never know when you’ve got Tommy in your team, what he’s got cooked up and when things are going to erupt.

“They’d all be in the sin bin these days – there’d be no players.

“Tommy wasn’t one to carry a game plan. He was out to defeat them physically and to bash them. Anything scientific was a bit too tough for Tom.

“He wasn’t too interested in that sort of stuff.

“(Fellow Jets halfback) Kenny Wilson was the best shot caller.

“Kenny wasn’t as rough or robust as some players but I couldn’t do it better than Kenny if I was out there directing traffic. He did exactly everything I wanted him to do.”

In 1983, Ryan didn’t bother coaching his Jets side.

“They sent Frank Farrington (Jets secretary) on a managerial tour of England with the Kangaroos (in 1982) and cannibals here were buying all my players,” he recalled.

“I said I was wasting my time. I didn’t care if I never coached again. I didn’t see coaching being a career move. That wasn’t what it was about.

“I remember getting a cab from Central Station to home a few years after the grand final and the driver refused to take the fare.

“I said, ‘Why not?’ He was an old Newtown man from way back and said he couldn’t take my money after what I did for Newtown.

“It was astonishing because that was his livelihood. He was so grateful. It was Newtown’s last hurrah – two years later they were gone.”

RULE CHANGERS

The domination of the Dogs of War prompted two rule changes – defensive lines were pushed back from five metres to 10 and teams catching the ball on the full in their in-goal could restart with a tap kick, rather than a drop out.

“If you’re good enough to change the rules that massively, then you’ve had an enormous impact on the game. They had to change the rules because of that side,” Ryan said.

“In the ’85 grand final, we had (Dragons fullback Glenn) Burgess in-goal and he couldn’t get out. That changed that rule and with the stroke of a pen.

“Everyone had to move back twice the distance. We stopped the game.

“They couldn’t score against us.”

Before his first training session with Canterbury in 1984, Ryan ushered his players together inside a vacant bar in the main Belmore Sports Ground grandstand for a harsh talk after Manly and Parramatta had belted the Bulldogs during the 1983 semi-finals.

“I told them they could start a game a fortnight ahead of Manly and Parramatta and still couldn’t beat them,” Ryan said.

“They didn’t have a clue what they were doing and I knew what I wanted to do and they could see what I was teaching them was of value.

“I remember telling them I was going to teach them about football.

“Chris Anderson, who was a favourite son, said, ‘That will be different, we haven’t had any of that for five years’. I said to (Langmack) that one day you’ll put all the pieces of the jigsaw together and wake up one morning and be onto something and know all about it.”

Langmack said: “Warren said: ‘It’s my way or the highway’ and we all bought in. We had to change the way we played. Luckily we had blokes who were sponges and wanted to learn.”

Ryan added: “Langmack, David Gillespie, Peter Kelly…frightening blokes when they were taught properly.”

FOOTY FEET

It’s all in the feet.

“Your foot movements are so specific,” Ryan said. “If you put one a little bit to one-side, you lose power – the transfer of weight and the drive.

“Newton’s second law of motion – dare I quote it – it’s to do with application of force over a distance which gives you a final velocity.

“If you’ve got blokes running at you and you’re applying this transference of weight correctly with your legs, and hitting with your shoulders, plus the advancing speed, it can have a tremendous impact, it’s frightening actually.

“That’s why the Dogs of War side were so frightening, they really hurt people because they were all trained with their footwork.

“I used to march behind them like a lieutenant when they were tackling the heavy bags and would tell them they were splaying their feet. Get it straight. It’s a terrifying force you can generate if you know what you’re doing.”

Originally published as Rugby league revolutionary Warren Ryan opens up on his coaching philosophy