Paul Kent: Why Rabbitohs will pay tribute to Lionel Potter when they face Manly in preliminary final

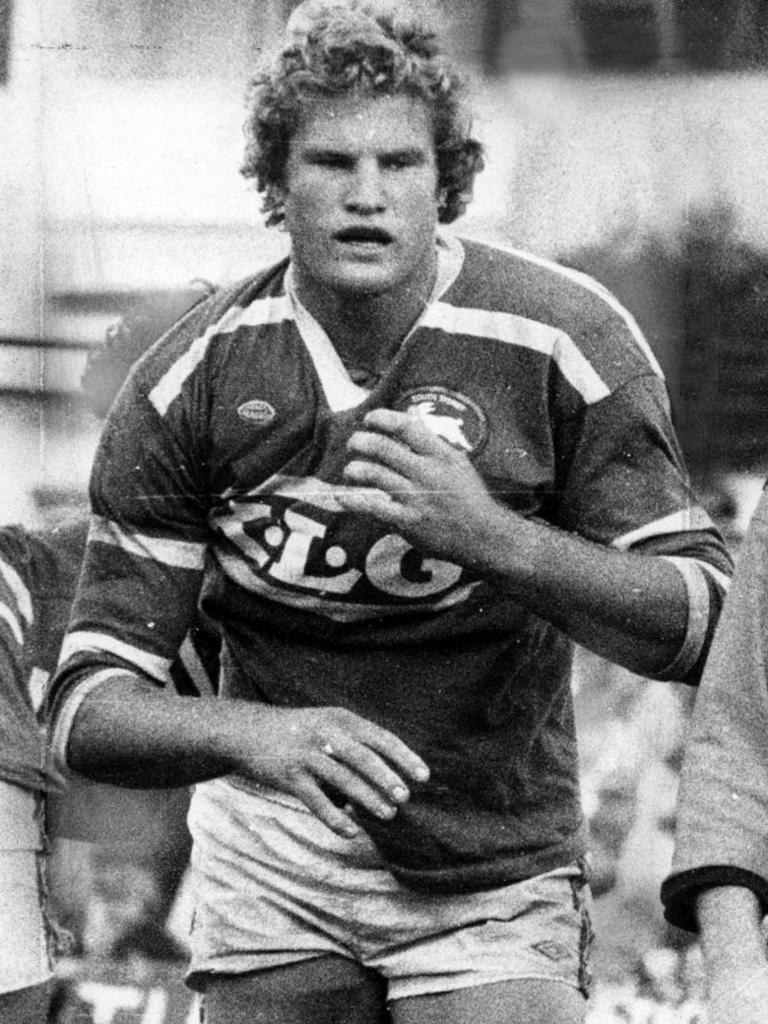

Lionel Potter was a man who wrote his way out of Parramatta Jail and into South Sydney history - with a bit of NFL notoriety for good measure, writes Paul Kent.

When South Sydney run out wearing black armbands on Friday night, for the memory of Lionel Potter, the soul of the club will be on their arms.

Lionel passed away on Saturday. He would have turned 85 on Tuesday.

“His contribution,” said Craig Coleman, “was as good as any player that has been here. I’m just so proud Souths are honouring him.”

Watch every 2021 NRL Telstra Finals Series match before Grand Final. Live & Ad-Break Free on Kayo. New to Kayo? Try 14-days free >

Lionel arrived at South Sydney with Jack Gibson in 1978.

They met some years earlier when Gibson would take players into the prisons to play footy and Lionel was at Parramatta Jail as a guest of Her Majesty, being formerly employed with Darcy Dugan’s Lavender Hill Mob.

“How long you got to go?” Jack asked one day.

He still had some years left on his run but Jack stayed in touch and Lionel, a constant letter writer, would write to Jack at Easts with various tips on conditioning and play and that sort of thing, and all enough to impress the coach.

Gibson told him that once he was released he would have a job for him and, when his parole came up, Jack helped out with a quiet word and Lionel was released and had a job as a conditioner at Souths.

One of his first jobs was to get Charlie Frith fit.

Charlie could hit like few ever could but that was no good to Jack if he wasn’t fit enough to last the game, so he turned him over to Lionel.

All these years later Charlie, now living in Roma, can still remember Lionel with him at Centennial Park one morning before work.

“I just have this memory of me vomiting and Lionel standing there, jogging on the spot, and then when I’d finished we’d go on,” he said.

“And then five the next morning he’d come and knock on your door and get you up to go running again.

“Everyone appreciated Lionel.”

While Jack moved on, Lionel, whose nickname was Henry, had Souths in his blood.

Some years later a young kid called Les Davidson rolled into training riding a red and green pushbike with his jeans rolled up to his knees to stop the chain grease staining them and thongs protecting his feet.

Lionel took one look at this sight and worried immediately, afraid that if Davidson was going to continue dressing like that he would get picked on.

He rang Des Lewis, who used to stop all the trouble from happening at the old card games up at Kings Cross, and told him he had a kid who needed to learn how to handle himself.

“Tell him I’ll meet him at Giles Gym tomorrow,” Des said.

The next day Lionel answered the phone and it was Des.

“He’s a snag,” Des said, which meant something completely different back then to what it means now. It meant a trap.

“Nobody will beat him in the ARL,” Des said, “he carries dynamite in both hands.”

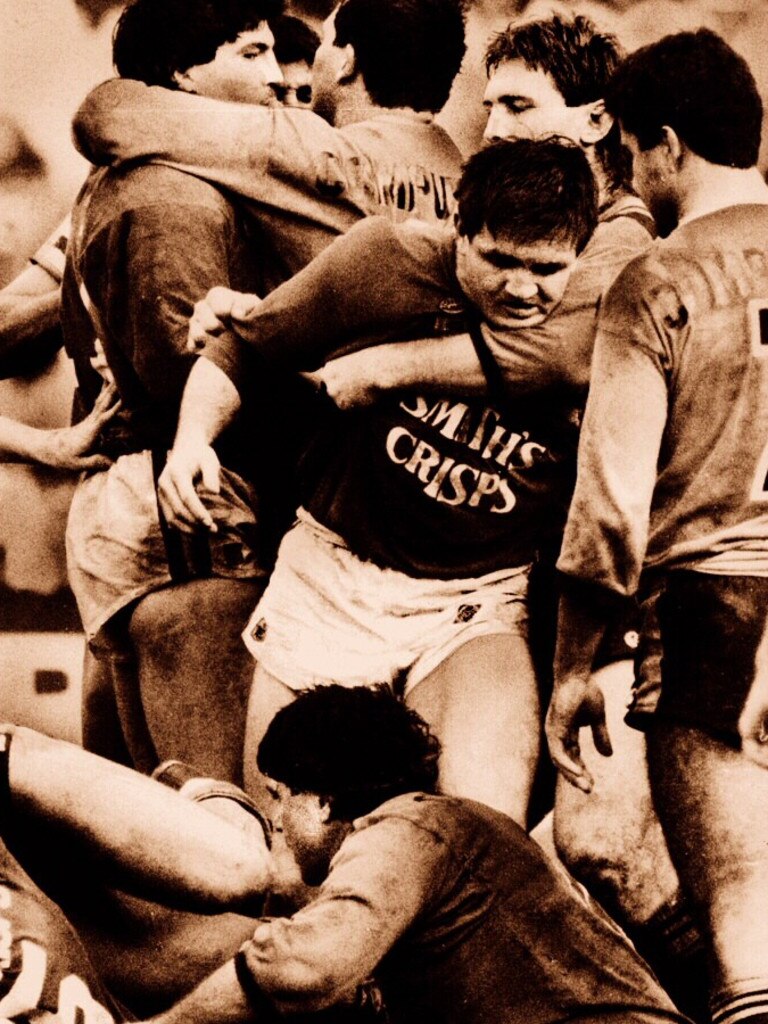

After that Lionel knew Davidson would be all right, which was fortunate because he arrived when Ron Willey was Rabbitohs coach and had inherited a pack high on toughness but light on subtlety, so he knew he needed to find more blunt ways to win.

The Rabbitohs came up with the ploy to start all-in brawls to upset the opposition’s rhythm and Dean Rampling was put in charge of calling it in a pack that boasted not only Rampling and Davidson but Rampling’s brother Tony, David Boyle, Mario Fenech and assorted others.

The call sign was Henry, named after Lionel. Rampling usually saved it for scrums but once Henry was called, and it was called often, the Rabbitohs would turn momentum their way.

Sometime around then the Rabbitohs went on their end of season trip to America and, when they landed in San Francisco, Lionel took them to watch the 49ers train.

Not long after arriving, former 49ers end RC “Alley Oop” Owens, a specialist coach, came down the tunnel, asking, “Where’s Coach? Where’s Coach?”

One of the Rabbitohs pointed towards a 49ers coach nearby.

“No, no, I’m looking for Coach Potter,” Owens said.

It turned out Lionel had been writing to 49ers head coach Bill Walsh for years and was well-known inside the 49ers organisation.

“Joe needs to see you,” Owens said to Lionel. Joe Montana had tennis elbow and wasn’t training that day but wanted Lionel to go in and take a look at him.

Lionel wrote letters regularly to Walsh and another former NFL coach, Chuck Nolan, whom he met through Jack.

In his time at Souths, Lionel had an influence on them all, but was particularly drawn to the forwards. He admired silent toughness.

Before games Tugger Coleman would always look across at Boyle whenever Lionel was nearby.

“Are you going to have a go today. Boyley?”

Lionel would look at Tugger and give a smirk.

And after every game when Boyle would collapse, wrecked with effort, Coleman would find Lionel and ask, “Did Boyley have a go today?”

Lionel always gave a smile and a wink.

As Lionel got older and his time at Souths ended after the 1999 season, he still followed the Rabbitohs, by now forever in his blood, and the players became his family.

Johnny Lewis, the fight trainer, was at the footy with Russell Cox in early 2005 when Cox looked over the heads in the crowd.

“There’s Lionel Potter!” he said. “I’ve got to talk to Lionel.”

They met at Parramatta in the 1970s but had fallen out of contact for many years, and for many good reasons, but that afternoon their friendship resumed.

“I’ve never heard anyone say anything bad about Lionel and my view is, if they did, they didn’t know him,” Cox said.

“He was a great bloke. He was exactly the same in the nick. Everyone admired Lionel.”

Cox shared time with Lionel at Parramatta Jail where Lionel got the boxing program introduced.

Earlier this year before Covid, they caught up again when Cox visited Sydney. They spoke for the last time just a few weeks back.

For 25 years Coleman would put a Christmas present for Lionel under his tree, which he gave him at Christmas lunch.

Before lunch was over, Coleman’s wife, Debbie, would load him with weeks worth of food to take home.

As he grew older, Ricky Montgomery, another former Souths player, would pick him up and take him to his doctor appointments or for whatever else Lionel needed.

Having given for so long, shared so much, the old Souths boys were looking after each other.

Just a few weeks back Frith called Lionel to tell him a mate of theirs was sick.

“Straight away he was up at the hospital,” Frith says. “Took him a paper. After that he took one up every day, even though he was too sick to read it.”

Then Lionel got sick with a series of small strokes.

Montgomery called him over the weekend and got no answer so went around to check he was okay.

This is the fate of old men.

Montgomery peeked through a window and saw the bed was not slept in and immediately got worried Lionel was down somewhere in his flat.

As he looked through windows, a neighbour told him an ambulance had taken him away on Saturday.

Lionel died later that day, the old Rabbitohs carrying a heavy heart all weekend.

“All he ever done was give, give, give,” Coleman said.

“And he wanted nothing in return.”

And so on Friday night the new Rabbitohs will give a small piece of them back to him, carrying him on their sleeve, a black arm band, as they strive to qualify for the grand final.

All they will need to do is what Lionel always did, which was give.

Clubs laugh off pointless NRL crackdowns

For 75 minutes the game was the kind you could put a bow on and drop into a time capsule to one day show people the greatness of rugby league.

The ball was in play for 61 minutes and 24 seconds when Penrith beat Parramatta on Saturday, which meant a massive 340 play-the-balls and took it into what is State of Origin kind of territory.

The Panthers and Eels had the ball in play for longer than any game all the way back to round seven.

By comparison, the ball was in play for 51 minutes and 59 seconds Friday night when Manly played Sydney Roosters, with just 268 play-the-balls.

Then what happens too often lately happened again, and the game was overrun by controversy.

Parramatta forced a dropout and, behind 8-6, fronted up to attack Penrith’s tryline once again.

Blake Ferguson took the hit-up off the dropout and Reagan Campbell-Gillard took the next one off the ruck, Mitch Kenny was unable to get up.

“Stop the game, stop the game,” the linesman soon says to referee Ashley Klein.

One more play and the game is stopped.

When Kenny went down Penrith trainer Pete Green did not go to Kenny, but instead went to the linesman to tell him to stop the game.

So with Penrith out on their feet and less than five minutes left and Parramatta pressing their line the linesman says “Stop the game”, just as Penrith wished.

Under NRL rules, the game can be stopped only after the trainer has carried out an “initial assessment”.

His decision to go straight to the linesman, rather than assess Kenny, gave Penrith’s defence more time to rest.

This one action, like every action in the NRL, had a consequence that affected the rest of the game.

Who knows if Parramatta might have won or if Penrith might have been even braver.

Given they have already got their reward, which was victory and a place in Saturday’s preliminary final while Parramatta fly back to Sydney this week, their season over, will we see the Panthers or any other team doing it again?

The NRL is investigating the incident. But even if it’s proven that the rules were broken, in the football club mindset any kind of financial penalty is irrelevant. Some unknown face in administration would pay it with money pulled from a well-lit poker machine in the leagues club, so no real penalty there.

It would have no impact on football departments and, particularly, the coaches who drive the win-at-all-costs mentality. All they care for is the result, not consequence or reputation.

For too long the NRL has operated with an “acceptable penalty” mentality.

They express concern at certain incidents, but not enough to impose a penalty strong enough to ensure it will never happen again.

So teams take them on, happy to take the risk and pay the price if they get caught.

It was a moment that changed the game, and nobody will ever know how.

Given the high intensity that it was played, that just five minutes was left and a two-point difference – and Penrith needed to find a break – Parramatta had a right to feel hard done by.

For too long the NRL has gone softly-softly on rule infringements. This policy of acceptable penalties, where teams decide it is worth the risk, continues to undermine the game.

Even Panthers coach Ivan Cleary has acknowledged as much. Cleary said recently in relation to another incident that coaches will continue to bend the rules as long as the NRL allows them to do it.

Cleary was imploring the NRL to act. They didn’t, and so on Saturday his team appeared to be the beneficiary.

For too long the NRL has had a soft mindset of acceptable penalties. They will punish a club but never enough to stop them, or any other club, from doing it again.

American sports punish teams with enormous fines but they also strip their draft picks.

It is why the last major salary cap scandal in the NFL was in the late 1990s, after which the NRL has had at least half a dozen.

The AFL has had no significant cap cheating since Carlton was busted and stripped of draft picks which set them back years.

With the absence of draft picks the greatest fear within an NRL club is competition points.

While this particularly indiscretion would not warrant that action, at some point the NRL will have to look at changing the rules.

Faceless fines are not the answer. Simple rules, and stern punishment, is.

The one punishment teams fear is losing competition points.

With no draft picks to strip from clubs, strip them of competition points in following seasons.

More Coverage

Originally published as Paul Kent: Why Rabbitohs will pay tribute to Lionel Potter when they face Manly in preliminary final