Inside story behind Jim Stynes’ Brownlow Medal winning season of 1991

Melbourne great Jim Stynes played 244 straight games, which stands as an AFL record. And his former teammates have opened up on the alternative methods he used, sometimes refusing to get treated by the club doctor.

Sport

Don't miss out on the headlines from Sport. Followed categories will be added to My News.

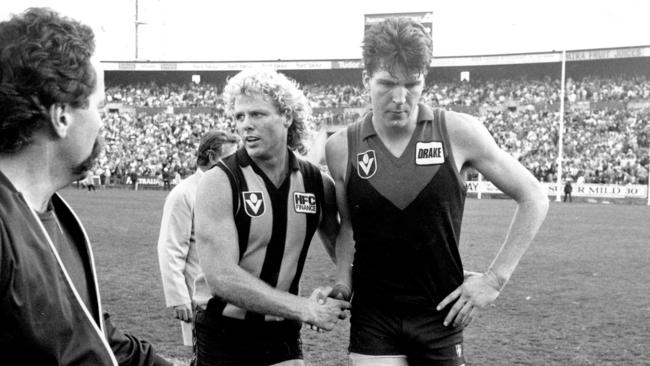

Damian Monkhorst can still recall the cheeky taunt from Jim Stynes.

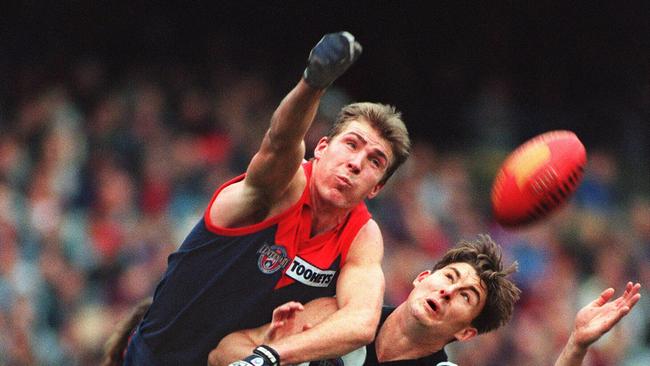

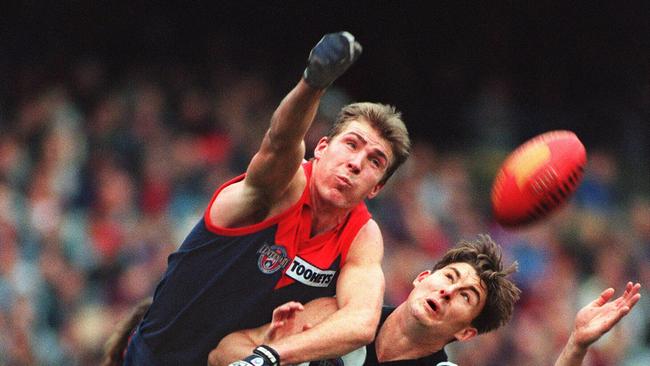

Throughout their duels in the early 90s, Monkhorst knew he had to physically dominate the aerial contests to get the upper hand.

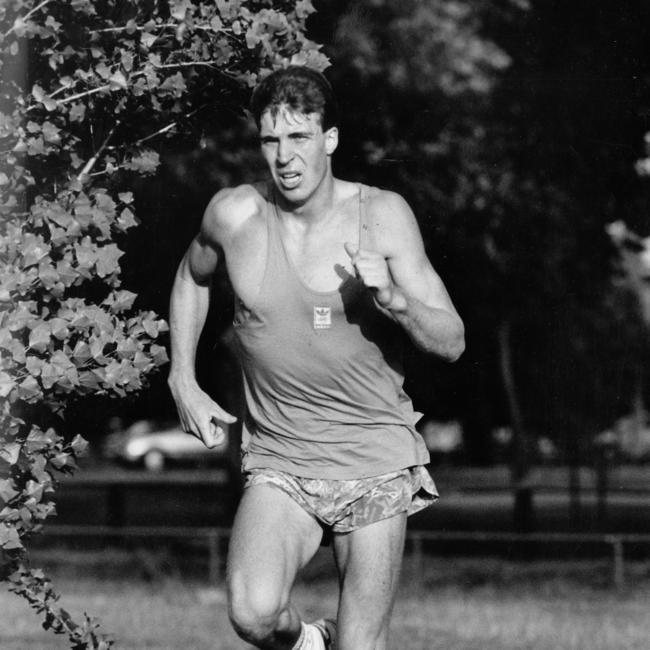

Because once the ball hit the deck, and Stynes turned on the afterburners, the aggressive Collingwood big man was no chance of keeping up with one of the greatest runners the game has seen.

“We had a great rivalry back in the day, Jimmy and I,” Monkhorst said.

“And I can still remember him always saying to me, ‘C’mon Monk-eeey, come for another run with me’.

“He was a different style of ruckmen back then, Jimmy, but he was bloody hard to play against.”

Relive classic AFL matches from the 60s to today on KAYO SPORTS. New to Kayo? Get your 14-day free trial & start streaming instantly

Years earlier, the Irish import had been written-off as a serious AFL prospect and dumped to play for Prahran, perhaps never to be seen again at the top level.

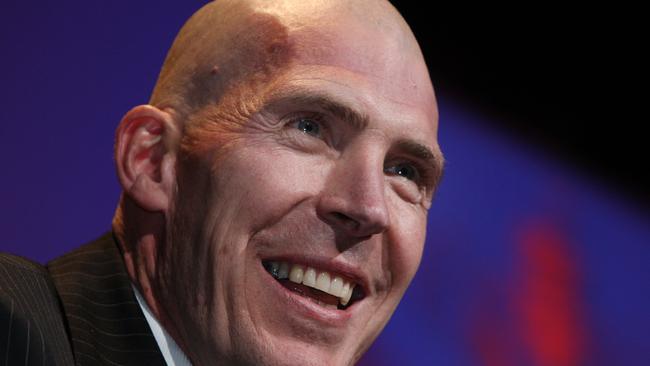

But there is good reason why Melbourne great Garry Lyon believes Stynes is one of the best stories in the game’s history.

After a slow-burn start to his career, Stynes became the No. 1 player in the game when he took out the 1991 Brownlow Medal, despite telling former teammate Chris Connolly on a run the morning of the count that he was simply “no chance of winning it”.

“He said there was just no way, and I remember telling him, ‘Mate, whatever you do, make sure you write a speech, in case you do win it. You definitely can win,” Connolly said.

UNDERRATED KICK

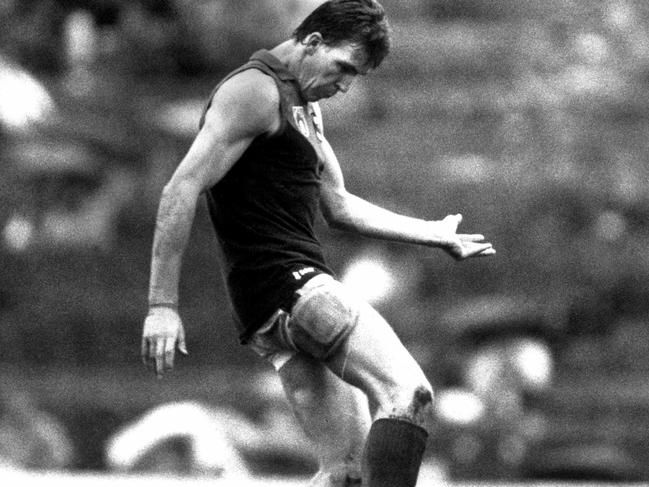

Loved by all of his teammates, Stynes not only had a huge heart, incredible courage and resilience, fierce determination, and deft touch with the Sherrin.

Changing the game for big men, Stynes could outrun everyone at the MCG, often without a break.

“You could see by the second quarter the other team’s ruckman would have his tongue hanging out,” Lyon said.

“His ability to gut-run non-stop was unrivalled and we used to run up Mt Buller and Mt Buninyong as part of the training, and he would go back home to Ireland and run up the mountains in the snow.

“But not only that, he was a beautiful touch kick. He was a glorious kick.

“He was probably my favourite player to lead to because he would just put the ball in space for you to mark at your own pace.

“His control off the boot was just superb.”

THE PAIN GAME

Tactically, Stynes gave an accomplished Melbourne outfit an edge under John Northey, as the Demons outnumbered the opposition in the back half and then sprang forward.

Midfield general Todd Viney said Stynes was an inspiration on the field in that 1991 breakout year, aged 25, as the Dees charged into the semi-final.

“He was getting really high numbers, up around 30 touches a game and no one had ever seen that back then from a ruckman,” Viney said.

“He revolutionised the game for the big guys and it was just like having another midfielder out there running around for us, really.

“The other ruckmen really tried to target him in the physical side of the game, no doubt. That was the only way they could calm his influence, to try and physically bash him.

“But Jimmy was as tough, physically and mentally, as anyone I played with.

“His ability to withstand that, cop it, and then say ‘right now it’s my turn. You give me pain in the contest, I give you pain everywhere else’.

“You could always count on Jimmy. You could always rely on him to deliver on game day.”

Stynes averaged 26 disposals across 24 games in 1991 to win the Brownlow by five votes, and the first of four best-and-fairest awards of his sparkling career.

That 1991 season was regarded by Lyon this week as the most outstanding individual campaign by a Demon in the AFL era.

He was red-hot between Rounds 16 and 20 in particular, polling 12 Brownlow votes in a five-week purple patch.

Connolly said “Northey has to take credit because he allowed Stynes to play to his strengths”.

“In the end, John Northey was ahead of time in the way the game was going. The linking the ball out of defence, and being able to maintain possession,” he added.

“As soon as Melbourne got the ball, they were a man up because the opposition could not run with him.”

BOUNCING BACK

Only four years earlier, Stynes’ career hit an early low point when he, in part, cost Melbourne a Grand Final berth when he ran over the mark in the dying stages of the preliminary final against Hawthorn.

Afterwards, Stynes copped a fearsome spray from Northey.

“Jimmy had his fair share of trials and tribulations coming over from Ireland, in particular that 87 preliminary final,” Viney said.

“But that only just drove him to become the player that he became.”

And his durability was legendary as Stynes played an AFL record 244 consecutive games.

He gritted his teeth through serious injuries throughout that span, including a broken rib and a medial ligament strain.

And some of his alternative healing methods were unconventional.

“He was into giving anything a go, but it was more to do with the strength of his mind,” Viney said.

Lyon agreed.

“He challenged conventional medicine,” Lyon said.

“Sometimes, he refused to get treated by the club doctor or physio, and instead he would go to a heath healer, or some witch doctor. He was that far ahead of the curve.

“One time he had a masseur wrap him in mud, and it caused a lot of angst sometimes.

“But I would say, let him do whatever he is doing because he hasn’t missed a game for eight years.”

PEOPLE POWER

And Stynes’ legend grew off the field in his work with youth organisation Reach and then in his money-raising days as Melbourne president, helping save the club from its own enormous debt.

He bravely fought cancer which ended his life in 2012. Last week would have been his 54th birthday.

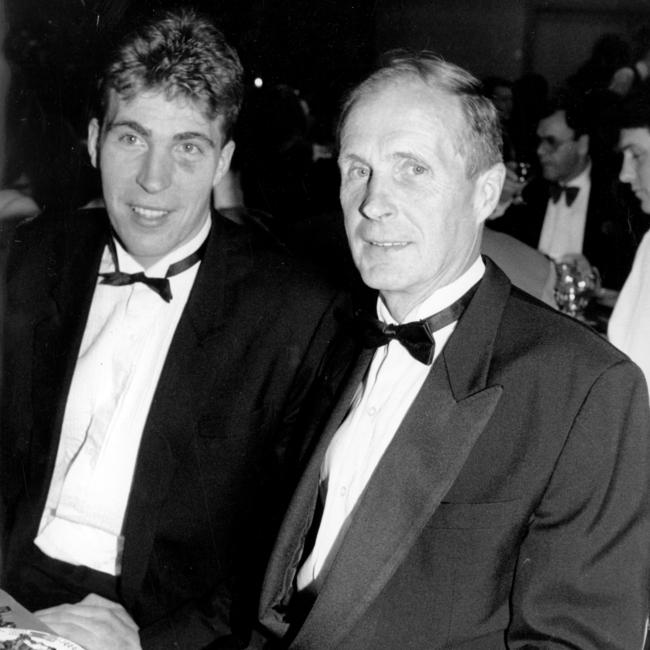

His brother Brian Stynes was immensely proud of Jim’s legacy on and off the field.

“You just had to marvel at what he was able to achieve, and how he did it,” Brian Stynes said.

“And then (after he retired) he went in to the charity work and that was even more amazing what he did there, and how he was able to get people to follow him, and eliminate Melbourne’s debt.

“He was a great organiser, and being able to get people to do things.”

MORE AFL NEWS:

Former St Kilda player Arryn Siposs joins NFL team Detroit Lions as undrafted free agent

HARD YARDS

His giant football journey started in the hills and paths around Dublin.

The Stynes Brothers were both talented runners who lived only four doors down from the coach of the Brothers Pearse running club.

That’s where his enormous motor first started to rev.

“We would do hills first and then we would run around the local area,” Brian Stynes said.

“And we lived at the foot of the mountains, so when we would come home, Jim would run up the mountains.

“And my mother would go up and collect him and bring him back down because it was much better to run up than run down them.”

Originally published as Inside story behind Jim Stynes’ Brownlow Medal winning season of 1991