The Soda Room podcast: Chris McDermott tells why two toes were amputated, and his pain at losing parents

Footy champion Chris McDermott has revealed how a simple loss in concentration and his status as a diabetic set in motion a train of events which led to emergency surgery and a month in hospital.

Crows

Don't miss out on the headlines from Crows. Followed categories will be added to My News.

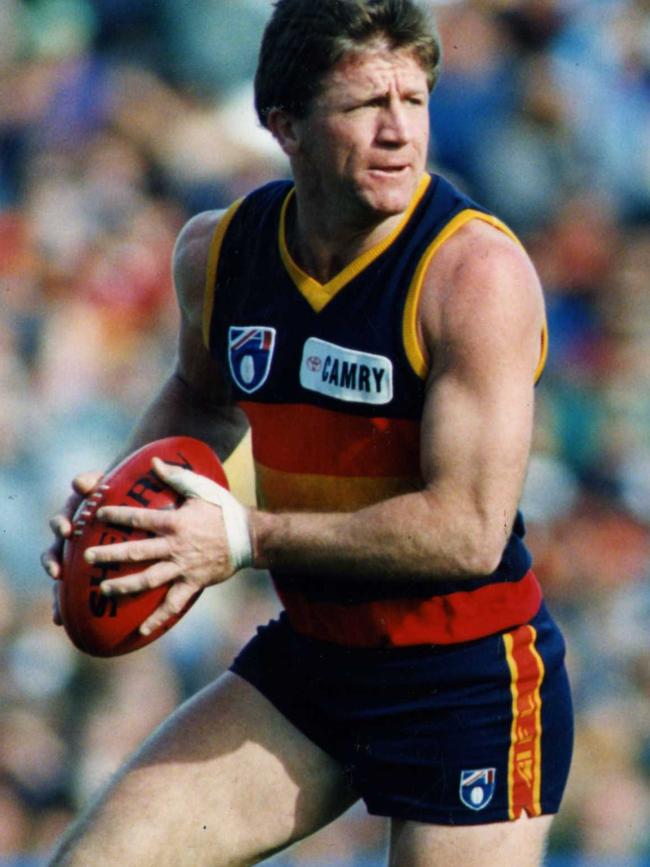

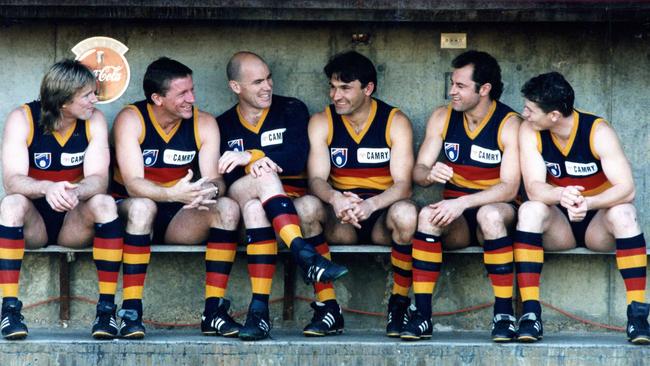

Inaugural Adelaide Crows captain Chris McDermott is training to run the New York Marathon despite having two toes amputated following a diabetes-related complication.

McDermott, 58, spent a month in hospital with an open wound where his toes once were as doctors worked to ensure the infection did not spread further into his foot and leg.

The Glenelg premiership star and Little Heroes Foundation founder has opened up about what caused the infection, losing both his parents to cancer when he was a teenager and his playing career with Mark Soderstrom in the latest episode of The Soda Room podcast.

McDermott, diagnosed as diabetic more than 20 years ago, said the chain of events which resulted in him losing two toes started when he nipped some skin when was cutting his toenail in December, 2019.

There was no pain, but his health deteriorated over the next 36 hours so he visited his doctor who discovered his blood sugar level, which should be less than six, was off the charts at 40.

SCROLL DOWN TO LISTEN TO THE PODCAST

Neither the doctor nor McDermott made the connection between his queasiness and the nail-trimming accident – until he removed his shoes and socks and discovered the toe was black.

“He put me into hospital,” McDermott said. “I was in intensive care that night. By the next morning, the toe next to it was black … and halfway up my foot is black, going towards my ankle.

“Now I’m worried about losing my foot. I know the toes are in all sorts of strife. He (the doctor) said we need to operate on this straight away before it’s too late.”

The operation was a success but while recovering, McDermott decided he would make an effort to try and run again for the sake of his family.

He started with a 1km jog, has gradually built up to 15km and will join a team, which includes Soderstrom, led by running coach Anna Liptak in New York in November.

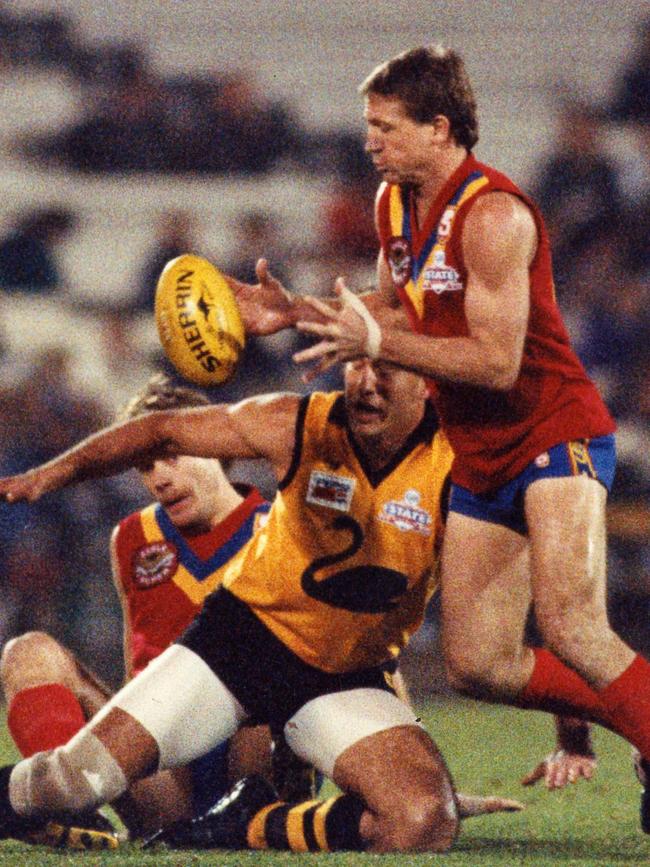

McDermott also revealed that the courage he displayed during 354 games for Glenelg, the Crows and North stemmed from a cathartic desire to ease the pain of losing both parents to cancer within a six-month period when he was 15.

“I liked getting hurt, if that makes sense,” he said. “I could justify it because of what happened. I felt like I couldn’t be hurt any more.

“And the physical pain was … cool, to be honest. I’ve always thought about it. I loved it (the pain). It was, it gave me a memory, and it gave me a reason.

“It (the memory of my parents) was my justification for playing and playing that way.”

McDermott said he had a pre-match routine of locking himself away from his teammates to mentally get himself into that zone.

“It was like going to confession,” he said. “It was just my place where I could get the anger and all the emotion that you carry with you.

“Some of it was good, some of it was bad, but it just got rid of it all and I almost felt like once I walked off the field, had my shower and got dressed, I could start the week fresh again.”

CHRIS McDERMOTT SPEAKS TO MARK SODERSTROM IN THE SODA ROOM

The Soda Room is presented in collaboration with The Sunday Mail.

Below is an edited transcript of the podcast – listen in full in the player above.

Mark Soderstrom: You look fantastic. What do you weigh now, and what did you play at because you look really slim, you haven’t blown out like we’re seeing with a lot of blokes.

Chris McDermott: Well, let’s hold that thought. So I played at about 85 kilos, for the majority of the career. I probably started about 75-77 kilos as a teenager, so fairly lean. Played majority the footy at about 85 kilos, finished and had a couple of years’ spell and probably blew to early 90s. And now I’m back down to 75 kilos.

Now, that’s not through hard work. I’d gone a little unhealthy and was crook for a while. So I lost a heap of weight and just haven’t been able to put it back on.

So I’m a diabetic now. And so that sort of challenges what you eat, and you will be careful with what goes in your mouth. So putting on weight, it’s been a real issue for me.

MS: And now, at 75kg you are doing something magnificent. So this November coming up, you’re running the New York Marathon.

CM: Yes. And you’re largely responsible for that, because I’ve seen that you have run it on more than one occasion … And 42km is a distance that I was never, I’ve never remotely been interested in running.

I don’t like running, never liked it at all – the most I’ve ever run is 10km at once. And that was a long, long way.

MS: Surely some of those pre-season camps so you must have run 15km?

CM: No, I would walk if I had the opportunity. And the game, you won’t remember – you might not have been born in the early ’80s – but it was predominantly, football was a walking game.

There was a little bit of a burst into a three-quarter pace and a little bit at full speed. But a lot of it was stationary, it was walking around the centre square – you go back and look at the footage.

And not a lot of the up and down running like there is in the game today. So we were very conservative with our energy. So I didn’t run a lot.

MS: You’re selling it a bit short by saying it was a walking game.

CM: Well, no, it was very physical. The energy was more spent in the physical nature. So it was a very physical game. It wasn’t an aerobic game like it is today. I think the aerobics has taken over and it’s nowhere near as physical.

But there wasn’t a lot of running and just running 42km – it has no interest with me at all until I tried to get my kids to get into the gym and start exercising. And I started running.

And one of my feet is only got three toes on it now, not five toes on it. So running a bit of … so there was this little bit of a challenge about how to run. And I thought oh, that’s OK, I can do this. I ran 1km, I swear as I sit here in front of you. I ran 1k the first time, it was as far as I could go. I was exhausted. Now I’m 58, so …

MS: Now you said about having three toes. Tell us about what happened with the diabetes and obviously now you’re going to run but what happened in the last couple of years.

CM: It’s quite a simple story that had a bit of a poor outcome. So I was going to bed on a Wednesday night and I thought I’d cut my toenails … as you do on a Wednesday night.

So I just had a glimpse and thought they could do with a little bit of a snip, so I was cutting and I cut the end of my toe. It was dark and, anyway, I was sort of doing a little recklessly and I nipped the end of my middle toe.

And didn’t worry anything about it. It didn’t hurt. So I went to bed, woke up the next day, and I wasn’t feeling all that well the next day. Went through the day and felt worse and worse as the day went on, got to Friday morning, woke up and just felt really ordinary.

So I went to the doctor, and he does a blood sugar on me. I think they just do that out of habit …

MS: Could I ask at this stage, how long have you had diabetes for?

CM: Twenty years. And I’ve got it relatively under control … Anyway this (the toe episode) was late November, early December 2019. So I went to the doctor, my blood sugar is 40 – it’s meant to be six.

So he’s looking at me, he’s got no idea what’s going on. And I’ve forgotten about cutting my toes. So he said you’re going to hospital straight away. Shipped me in to hospital.

And the doctor and the orderlies have come out, seeing me and they can’t work out what’s going on. Got no idea.

And he said you’ve gotta take all your gear off. We’re going to do a full body because we can’t work out what’s going on sitting on the bench, and took my shoes off. And my middle toe is black. Not brown. Not light brown. Charcoal black.

MS: And you hadn’t noticed this the last couple of days?

CM: Nope, I had no idea. I had no idea. There was no pain. There was no discomfort. Yeah, I’m feeling woozy. So I’m not feeling the best. We’ve all just collectively sworn.

And he’s looked at me and said “Oh”. Just sent me straight up to the intensive care and he said we just need to work out what’s going on here.

He said what’s going on (with your toe). I said well I cut my toenails and cut the end of my toe … So he put me into hospital. In intensive care that night.

By the next morning the toe next to it was black. So I’ve got not just one but two, and halfway up my foot’s black going towards my ankle so you can almost see it going up your leg.

MS: And what are you thinking at this point?

CM: My brain’s clicking in the gears and I’m saying “Oh oh”. Now I’m worried about losing my foot. I know the toes are in all sorts of strife.

And he said we need to operate on this straight away before it’s too late. So operated on. So they’ve peeled all the skin off my foot right up to my ankle as they operate it on, cut my two toes off and left it open for a month.

So I had to lie in hospital … and for a month I just sat there and hope that it didn’t start going up my leg.

MS: So you’re sitting there for a month. What’s going through your mind is it your mind changing continuously?

CM: Not really. It’s one of those things well … you idiot. You should have known and you did know, and you just had a brain fade, so in the end, what will be will be.

I don’t think there’s any point … I must admit I had 12 hours, probably the first 12 hours when I was in there feeling pretty ordinary and not being overly impressed with life.

Then you get over it and you just soldier on.

MS: Do you have any pain there at all?

CM: No, nothing. You know, the phantom toe syndrome occasionally where you think they’re there, you bend your toes inside, you shoe and it’s like, “Oh, no I don’t have anything there”. It’s a quite a weird feeling.

I never thought I’d be able to run again, because it was really hard getting on your toes …

So that was the idea of going back to run, I just wanted to be able to run for my kids’ sake and for family’s sake and taking the dog for a walk and just want to be able to do all those things.

So 1k, all of a sudden, I got the four K’s then five. Now I’m at 15. And the thought of running a marathon became almost like, this is going to be cool, I’m going to be able to do this. And that’s something before I’m 60 that I’d like to do.

MS: So this is quite a significant marathon for you in November, given that you’re running without the toes.

CM: It’s huge. It’s just one of those things that sometimes I think your brain needs to do. I need to do this for, a bit selfishly …

MS: So did losing the toes, did it change you in any way or did you just take it within your stride, pardon the pun?

CM: No, I think it changed me. It made me feel really mortal, which is sort of fun. I think when you play footy … you like to believe that you’re immortal and nothing hurt.

I tried to think nothing can hurt me. Nothing matters. You can overcome anything. Until this. And this challenged that thought. And I guess I need to challenge it back if that sort of makes sense.

So I feel like it’s something I almost have to do. And footy for me was a bit of that same challenge that every week was a mental, physical challenge.

And we’ll probably go back to why that was. I’ll jump in now and tell you … so my parents died when I was 15, probably within about six months of each other. And so everything became a bit of a challenge after that.

MS: So you’re 15 at this stage. You’ve got your brother and your sister, you stayed in your house? Is that right?

CM: Yeah. So this is 1980. ’79 into ’80. My mum had breast cancer and had it for probably three years, four years in a really primitive time for that illness. And brutal time, you know, the radiation therapy and chemotherapy was around but it wasn’t like it is today.

So there were challenges and we used to have to go to hospital with her when she’d have that sort of treatment because Dad was working.

And so she’d drive herself, go and get the chemo, get in the car and drive again, and you sort of think of it now and it was a bit weird, but in the end, you do what you do and it was life for us … but mum was crook. She fought the fight and then died in, you know, in her early 40s in ’79.

Dad, Dad was fine. And he said to us one night, I remember him sitting the three of us down one night and he said: “You know how your mum was crook, we never really told you and explained to you what was going on? If that ever happened to me, would you like me to tell you, so that, you know?”

We said of course we would. He said: “Well, I have too.”

And he went really quickly … almost gave up in that sort of sense. But … we had some great support.

So (Glenelg SANFL player from the 1950s and prominent SA businessman) Brian “Tom” Rundle, he just got us this load of food and kept on dropping it off our house.

And we had great support from people around who just helped us get through. And then you sort of find a way to manage your way through

MS: Who cooked? Who did the cleaning and all that?

CM: My sister was a diamond. She was 14, she left school straight away, got special compensation to become a hairdresser. So she had a hairdressing salon at Seacliff. And so she went there.

Brother (who was a year and a half older than Chris) was a police cadet, so he was in the police force … in the academy … that was when they used to do two years at the academy … and he’d come home on weekends.

MS: It’s so hard to comprehend … I don’t know whether I’d be able to do it. But did you just did it? You found ways …

CM: You just did it. And so again, you know, we all had our support networks, if that’s what you call it. But so, my sister had her hairdresser. They became really good friends and great friends and they had a family so they really looked after her.

My brother was a bit older and had a girlfriend and had the police force.

And of course the Kernahan family were massive for me. And so I had a really close relationship with them obviously through Stephen and Gary and David, and Annette and Harry were fantastic.

There was a misconception for a while that I went and lived with him, which I didn’t. So the three of us stay together and snuck our way through and, you know, in the end, there are plenty worse off than we were.

MS: I think most people, when I talk about you as a footballer, the two things that come to mind always, to me, are leadership and courage. Did that courage come from that upbringing?

CM: Without doubt. I liked getting hurt? If that makes sense.

MS: Physically? When you’re playing? Would you put yourself in a position to …

CM: Absolutely. I could justify it because of what happened … I felt like I couldn’t be hurt anymore. And so physical pain was sort of cool. It was … bring it on.

Not to say it didn’t hurt, at times, but it was cool. I’ve always thought about it. I enjoyed it all the way along for 15 years, I loved it. It was just, it gave me a memory. And it gave me a reason.

But it was my justification of playing and playing that way. But I wouldn’t have said it to anybody.

So you have a routine, my routine was to go in there and have my two minutes in there where you lock yourself away and just get yourself into that area and that zone that you needed to be in. And that was my space. And that was my work.

And then as soon as I was out of it, I was completely different. So I wasn’t what you saw on the field off the field. I loved going out I loved my mates at that stage and was completely different.

But just for those … I loved those 2½ hours, loved them.

MS: So that was your way, I suppose almost a legacy of your parents and what you went through … But it was like your battlefield?

CM: It was like going to confession … it was just my place where I could get the anger and all the emotion that you carry with you … all that baggage you carry with it.

Some of it was good, some of it was bad, but it just got rid of it all and I almost felt like once I walked off the field, had my shower, got dressed, I start the fresh week again.

And you go away, and then you build up all that stuff, you get rid of it, and then you start again. So I loved the routine, the process and the ability to get all that stuff out of your system on a weekend.

MS: Thank you so much for joining us Bone, it’s been an absolute pleasure. Congratulations on everything. And one thing we didn’t even really get time to touch on at all. But I think it is certainly worth noting … what you’ve done for Little Heroes Foundation and for 26 years now I think you’re up getting closer to $40m that you’ve raised for kids is unbelievable. So congratulations on that too.

CM: Thank you for having me in The Soda Room.

More Coverage

Originally published as The Soda Room podcast: Chris McDermott tells why two toes were amputated, and his pain at losing parents