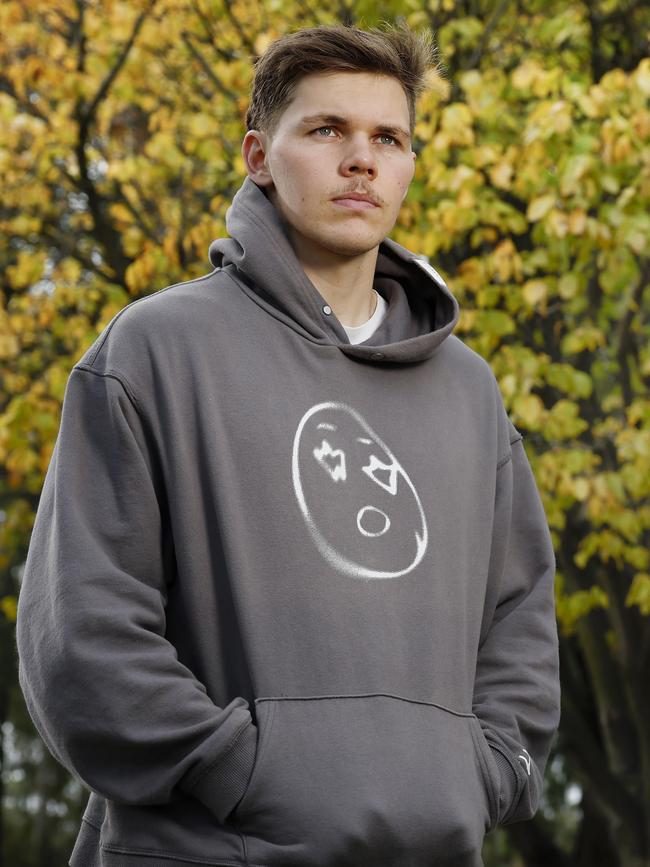

Cooper Hamilton opens up on mental health and the challenges of life after being an AFL player

Cooper Hamilton’s whole identity was football — until it couldn’t be anymore. The former GWS player opens up on the challenges he’s faced and mental health battles during his AFL career.

AFL

Don't miss out on the headlines from AFL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Cooper Hamilton was running down the wing last year when it dawned on him.

“This sucks.”

Playing state league football for Greater Western Sydney, the then-AFL-listed player just didn’t want to be there anymore. Hamilton was wracked with performance anxiety, and torn by a will to do his small town proud, his own identity and the balance of his mental health and what was best for the team.

An impossible balance to strike that literally ended in tears – a lot of them.

“I had a game against I think it was Frankston at Blacktown one day, and I thought I was happy to be out there,” Hamilton said.

“And then in the middle of the first quarter, I was running around the wing, and I was like, ‘I just don’t want to be here’.

“Like, ‘This sucks’.

“I genuinely think I touched the ball two times and after the game, I was just a shell of a person.

“I went to the car, called up the club psych who I had been seeing outside the club, and just broke down in tears and said, ‘I don’t think I want to do this anymore’.

“I drove back on the way home and I was — just bawling my eyes out, and I was like, ‘Nah, this isn’t, this isn’t for me’.”

From the tiny town of Colbinabbin in north Victoria, Hamilton knew he needed to get home, but the responsibility of a team and a contract weighed heavily.

“And then three weeks later, I was ruled out for the season again,” he said.

“I was a TBC (on the injury list) for ages. I spent 10 weeks trying to de-load my foot and then start running again, build back up, and then it would just get sore again. That went on for 10 weeks.

“I went and saw a surgeon, and he said, ‘We’ll do surgery’. And as soon as I heard that, it was like a weight lifted off my shoulders.

“I was finally like, ‘I don’t have to look like, this is me just pretending (I’m fine)’. Then it was that I was getting surgery on my foot, I’m not going to play for X amount of weeks, what will happen will happen. I could just enjoy the rest of my time, there’s no more pressure on me to perform. My mood changed so much after that.”

A message from Cooper Hamilton ðŸ—£ï¸ pic.twitter.com/8sLREbWG0K

— GWS GIANTS (@GWSGIANTS) September 20, 2023

Copper Hamilton is on the look for... the next Cooper Hamilton 😂 pic.twitter.com/URtt22H0Tz

— GWS GIANTS (@GWSGIANTS) January 23, 2025

Working as part of the Giants’ media team proved a distraction in difficult times, but Hamilton isn’t alone.

Now seven months down the road since he was delisted after eight AFL games, Hamilton still refers to his path out of football as like having his GPS switched off, but he is trying to find his way back to the highway.

It’s not a case “woe is me” for Hamilton, aware of the perspective that this is the “real world”.

But it’s reality.

As Geelong superstar Bailey Smith laid bare his personal struggles with mental health this week, AFL players are calling on mental health professionals for help more than ever before.

The AFL Players’ Association Insights and Impact Report, which was released this week, revealed that almost 800 current AFL and AFLW players had engaged with mental health support in 2024 – up 17 per cent on the previous year.

West Coast premiership defender Will Schofield said challenges that evolved while playing “pale in comparison” with those that came upon leaving the AFL system.

“Transitioning out of professional sport isn’t just a job change; it’s an identity shift,” Schofield said.

“You go from knowing exactly who you are and what you’re doing every day, to waking up and wondering, what now?

“Even with the study I did, work placements, media experience, and strong networks,

five years out and I still have days where it’s hard. The structure, direction, and that deep sense of belonging that a footy club gives you is no longer there.”

Schofield lost his father while playing and his brother soon after he retired, which he said compounded what was “a lot to carry”. He sees a psychologist regularly.

“To players still in the game or those recently out: it’s going to be hard, and that’s OK,” he said.

“You’re not failing because it’s tough. It’s meant to be tough. But don’t hope things will get easier – take responsibility, reach out and persist until you find what works for you.”

Performance anxiety – which refers to the anxiety experienced in anticipation of or during important tasks performed in front of others, also referred to as stage fright – became reality for Hamilton in his time in the AFL and still remains with him back in Melbourne playing for Carlton’s reserves this year.

“Every time I would go to play, I would be thinking, ‘Oh, geez, I have to get a kick, or else’,” Hamilton said.

“My mood throughout the week would be dictated on how I played on the weekend. And then if I played, I’d get to the Saturday and I’d be compounding even more performance anxiety. And be like, ‘You played last week. You can’t play this week again.

“And it just went over and over again. And that’s like, I was only in the system for three years and that’s how I felt. I couldn’t imagine how, like, some of the fringe players deal with some of the stuff that they go through.”

Then came his exit from the AFL in September 2024, axed after three years after being picked up by the Giants in the November 2021 rookie draft just two weeks after he graduated from high school.

Hamilton has been inundated with messages from footballers – both former and current – who have experienced similar levels of disorientation in their transition out of football and in life.

“I’d say now I’m starting to feel a little more comfortable,” Hamilton said, now a vlogger on his YouTube channel and sinking his teeth into social media.

“I still have no idea what I’m doing. But I’ve got little things to keep me sidetracked and that’s sort of why I’ve learned to do this social media stuff. It’s to try to keep myself busy, because I don’t know what I’m going to do. I started with one video – way back in November – where I said, ‘I have no idea what I’m going to do’.

“I didn’t realise that football was actually my identity. From there, I got a lot of messages and I realised, OK, a lot of people feel like this.

“I was getting messages from people from all walks of life. People with families, a bunch of kids, 40 years old and they just quit their job and they have no idea what they’re doing as well and that you don’t have to have life figured out. I talked about how I was lost and didn’t know where I was going … and what am I if I’m not playing footy?

“There’s so many worse positions to be in. Relative to what I’ve experienced, this is extremely difficult for one of the most difficult things I’ve had to go through personally, and that’s not to compare it to anybody else’s situation.

“But to have, like, every single minute of your life dedicated to pretty much being the best athlete you can be and the best footballer you can be … and now I’m entering the real world. Like, what do I do now?”

The rookie gets his shot 🔥

— GWS GIANTS (@GWSGIANTS) April 28, 2022

Cooper Hamilton will make his AFL debut this weekend!

Details 📠https://t.co/9sIFDQ6jBjpic.twitter.com/facDPDQaA0

Social media has been identified by players as a key vehicle of stress.

Western Bulldogs utility Rory Lobb says he has learned to shut out external noise in a bid to maintain strong mental health.

“It’s hard for me to explain how I’ve got to where I’ve got to,” Lobb said.

“My soon-to-be father-in-law Steve Rosich has been in the industry so I’ve got him to lean on when I need to … I have high standards of myself of my football game and he can calm me down a bit when I think I’ve had a bad game and say, ‘You’re doing good things’.

“I’m always a glass half full kind of guy with my football. I just expect so much out of myself. I’ve just let everything go. Whatever gets said about me that’s not in my inner circle or at the football club – everyone’s going to have an opinion no matter what.

“The Australian culture likes to bring people down and it’s always going to be like that. The more that you can stay true to yourself, and the way that you go about it and only value things that mean the most to you with family and friends and people that are around you most of the time, I feel like you’re always going to be in a good headspace because anything that’s said outside of that, you can’t dictate people’s opinions.

“Anything that’s said about me that I don’t feel like is true to myself, I know what I’m feeling on the day and those people don’t know me personally, so I just let it brush off. It’s a pretty good way to go about it, to be honest.”

The AFLPA Insights and Impacts report released this week also revealed AFL Women’s players are accessing mental health support more than ever before.

Former player Kate McCarthy said she was often wracked with performance anxiety, even for training sessions, with team selection, balancing work commitments and maintaining relationships all part of the growing pressure.

“I didn’t only get anxiety around playing – I got it around training, because you’ve got one training session to show why you should be selected,” she said.

“It affected me most when I was in it – and it affected so many different parts of my relationships with people.”

Clubs want to do more to support players.

Hamilton said a “stigma” remained around mental health in football clubs, but he credited his former coach Adam Kingsley as “the biggest advocate of a coach that I’ve had for the mental side of his players”.

Hamilton doesn’t know how the AFL can improve in the space, but he said social media remained a significant roadblock.

“I am genuinely frightened by what it might look like in 10 or 15 years, when the kids coming through have had their phones since they were eight years old,” he said.

“It’s not even just AFL – it’s life in general. The mental health of people, it seems like it might even trend to a worse space.

“You see the relationship between social media use and mental health issues – and you can only imagine how much worse it’s going to get.”

Originally published as Cooper Hamilton opens up on mental health and the challenges of life after being an AFL player