TasWeekend: Our architects become house proud

TASMANIAN architects have become adept at proving bigger isn’t always better. And in doing so, have we forged an architectural style to call our own?

Real estate

Don't miss out on the headlines from Real estate. Followed categories will be added to My News.

ORSON Welles is credited with saying, “The enemy of art is the absence of limitations”, a comment on how the true skill of any artist is demonstrated by how they can work within their constraints and still create something remarkable.

Welles’ comment may well strike a chord with Tasmanian architects, in that residential design in the state is largely defined by their ability to work within the constraints of not only our landscape and environment but smaller budgets.

Not only do Tasmanian architects find innovative ways of dealing with those constraints, they frequently turn those solutions into features. If there is such a things as a “Tasmanian architectural style”, says James Jones, principal at Jones Moore Architecture in Hobart, it is to be found not in the outward appearance of a building, but buried in the design brief and the designer’s inspiration.

A look through the architects’ statements from past winners of the Tasmanian Architecture Awards clearly shows common themes: embracing the natural environment, being sensitive to place, passive-solar features, good use of natural light, repurposing existing structures and materials, and doing more with less.

“The idea behind the architecture can be quite hidden and people will usually interpret it from the visual aspect, but you need to understand where the building has come from,” Jones says.

“There probably is such a thing as ‘Tasmanian architecture’, but I don’t think it is about style. It is more about those other influences. If you look at some of the Tasmanian Architecture Awards winners in recent years, they are often quite modest houses, they’re not huge buildings. Tasmanian architecture is probably characterised by lower budgets and the need for invention through necessity rather than largesse.”

Professor Kirsten Orr, head of the School of Architecture and Design at the University of Tasmania, agrees, saying she has noticed a definite theme of “doing more with less” since moving to Tasmania from Sydney this year.

Orr says a lot of this imperative derives from the unique concerns when designing and building a new home in Tasmania, with its often challenging urban and natural landscapes.

“I think it is a theme that has arisen in response to some really distinctive sites,” she says. “You’re often working in these really unique places and Tasmania’s climate is quite different from the rest of Australia as well.

“And there is a definite sensitivity around the heritage aspect of the built environment here. Even if we’re not talking about really old buildings, architects are still working with what they’ve got. They’re not going to bulldoze a site flat and start again unless they absolutely have to. More often the existing structure is incorporated into the new one somehow.”

Orr says Tasmanian architects are rarely presented with the huge budgets of bigger projects in large mainland cities, which forces local designers to be much more innovative to get the same result. This has led to a certain approach to the use of building materials.

I’ve noticed there is a very clever use of colour here ... making the most of available light

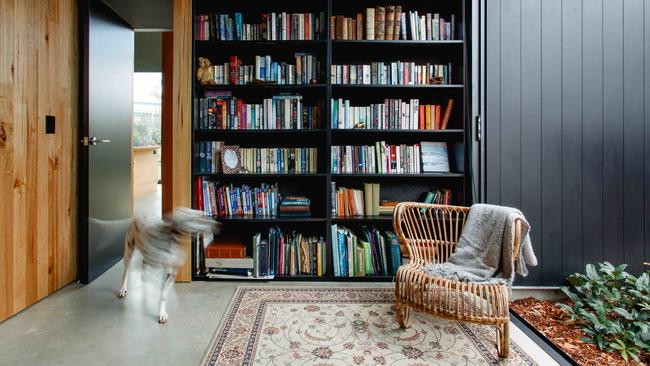

“Tasmanian architects tend to use standard materials in exciting new ways,” she says. “Or they find ways to use the material’s natural appearance as a feature in its own right, highlighting the qualities of the materials in ways that mean they don’t need to be painted or plastered over. Using timber products is obviously a big theme here but instead of painting it or hiding it, we tend to see clear finishes.

“I’ve even seen a house that used the timber from an old collapsed barn as a design feature. All the timber was painstakingly collected and repurposed and it has this beautiful patina that you don’t get with new timber, which would have cost twice as much with one of the character.”

Carly McMahon, who has a Master of Architecture and works as a designer with Liminal Studios, agrees that Tasmanian residential architecture is distinguished by a spirit of experimentation with materials, using traditional materials in non-traditional ways.

“Quite often you find architects trying to find the most cost-effective material and using it in a really creative way,” she says. “And homes do tend to be a bit more pared-back and modest. You don’t want them to overpower the landscape they’re in. I think it comes from seeing how creative you can be within certain constraints.”

Jones says one of the drivers of architectural innovation here in recent years has been the migration of seachangers and treechangers from the mainland, resulting in the arrival of fresh perspectives and bigger budgets.

“Whatever people’s reasons may be for moving to Tasmania, whenever it happens it means there are opportunities to create homes for these people,” he says.

“TV shows like Grand Designs mean people generally are starting to take more of an interest in the concept of architecture, so they are more open to trying new ideas and working closely with their architect. That doesn’t necessarily mean that for a really big budget you get a really good building. It comes down to a lot of things, like the relationship between the client and the architect and how their ideas coalesce.”

And there are some specialised concerns to take into account when designing a home in Tasmania, such as the distinctive quality of the sunlight, because of our high southern latitude and the sun’s low angle in the sky.

“The sunlight here is not as bleaching as it is in, say, Western Australia, but it is still quite powerful at certain times of year and understanding light is really important here,” Orr says. “In the winter you want as much reflected light as possible coming through the home, and then you get those long days in summer which changes things again – which is why I’ve noticed there is a very clever use of colour here in Tasmania, making the most of available light.

“Thermal mass is also deployed very strategically by Tasmanian architects for similar reasons. Tasmania has quite a mild climate, which allows us to be more experimental in the ways we look at spaces, how to keep them cool, open up to the views and so forth.”

Awareness of and respect for the landscape and environment are common markers of Tasmanian residential architecture, with designs tending to work with the topography of a site rather than against it, and with a preference for bringing the outside inside.

A great example of this is the so-called Five Yards House. Designed by Archier, it won the Esmond Dorney Award for residential architecture, the sustainability prize and the People’s Choice Award in this year’s Tasmanian Architecture Awards. The home is a modest one with a small footprint and is characterised by five garden spaces incorporated into the layout.

As a result, each part of the Howrah house has a view through full-wall double-glazed windows into a different garden, making the outdoors an integral feature of the interior, and vice versa.

This blending of inside and out is also a distinctive feature of largerscale projects such as the Shearers Quarters at Bruny Island, by John Wardle Architects, which features expansive windows in the living area that drink in the sweeping scenery, making it as much a feature as the timber cladding the walls.

There is definitely a strong connection to landscape or site in Tasmania, “especially given so there are many opportunities for putting residential buildings in beautiful places here,” McMahon says. “So there is certainly a lot of consideration given to the way a building might sit within that landscape and in its own site.”

Awareness of the weather is another issue that often comes into play, and the Alcorso Courtyard House – which is now part of the Mona site – is a good example of this. Designed and built in the 1950s by Claudio Alcorso, it was designed to embrace the views of the Derwent while also incorporating an enclosed courtyard, which would be sheltered from the strong southerly winds while also providing an outdoor space.

Tasmania has long had a reputation as a hub of architectural innovation. Orr says this is the main reason she moved to UTAS after working for the University of Technology in Sydney.

“It was quite deliberate, coming to Launceston,” she says. “It is regarded as one of the top schools in Australia and I had my eye on it for some time, so I jumped at the chance to come here.

“Tasmania has a reputation for being a centre of art, culture and architecture. When I was a student in the ‘90s, Tassie was a destination for aspiring architects. Students would make a pilgrimage here to work on projects.”

Jones, who was based in Melbourne for five years before returning to live in Tasmania this year, says he has noticed a distinct positive cultural shift since he last lived here.

“I have seen an exponential increase in the quality of food, the arts scene and architectural design. It has all matured greatly in that short space of time,” he says.

But he also reiterates the spirit of invention and innovation in Tasmania was very much alive and well long before now.

“Those environmental elements of design which are so central today have been around since the 1970s,” he says. “It started with the energy crisis of 1972. People were just as considerate of energy use and conservation back then, but the systems have only really started to appear on the shelf now. In the ’70s and ’80s in the School of Architecture in Tasmania, people were prototyping heat pumps with parts out of refrigerators, which was seen as a bit kooky at the time, and people were experimenting with solar panels, which was also a bit out-there, and now both of those things are subsidised by the government, they’re mainstream.”

Tasmania has a reputation for being a centre of art, culture and architecture

But apart from the largely hidden architectural concerns such as energy efficiency, budget, repurposing and so on, any firm concept of a Tasmanian visual or structural style remains elusive.

“Trying to define a Tasmanian style is a bit like asking, ‘Is there a NSW style or a South Australian style?’,” Jones says.

“The answer is yes and no. In the 1960s, a Sydney school developed a ‘nuts and berries’ trend with brick and timber and glass, which is recognised as a style. But there’s a long-running debate about Sydney versus Melbourne architecture.”

As Orr says, “We’ve been trying to nail down a definition of the Australian style forever. And defining the Tasmanian style is just as problematic. Nothing is ever a truly blank canvas. Each design will always be derivative of something else. If I had to describe Tasmanian architecture, I would call it a modern aesthetic, but not completely shiny. It has a patina and an edginess, there is a materiality to it, highlighting the inherent qualities of the materials, not covering them over with something else.”

For more great lifestyle reads, pick up a copy of TasWeekend with your Saturday Mercury.