Why Anthony Albanese can’t be over the moon after US trip

Anthony Albanese’s warm rapport with Joe Biden was on display during his state visit, but it remains to be seen if it was a success in style as well as substance.

World

Don't miss out on the headlines from World. Followed categories will be added to My News.

When American astronaut Neil Armstrong took his first steps on the Moon, the images were shared with 600 million people around the world by Australia’s Parkes Observatory.

Joe Biden proudly told that story to welcome Anthony Albanese to the White House this week, both as an example of what Australia and America can do “when we stand as one” and to encourage the allies to take “a giant leap together toward a better future”.

It was a thoughtful touch as the President and Prime Minister sought to expand the alliance beyond its military roots into innovative new areas, including an agreement for US commercial space vehicles to launch from Australia.

But Biden’s choice of anecdote was an implicit reminder of the traditional American view of the relationship that does not always sit well in Australia – particularly in corners of Albanese’s Labor Party – in which the US conquers the world (and beyond) and its deputy sheriff down under tags along for the ride.

Perhaps that is nevertheless preferable to the alternative: an America led by an isolationist president with little regard for alliances. After four years of Donald Trump and with a genuine possibility of four more, Albanese ended his visit to Washington DC by sounding a diplomatic warning – and promising that Australia would “always pay our way”.

“There will always be challenges here at home that seem more pressing, more relevant and more real than the concerns of other nations far away,” he said in a major speech before Vice President Kamala Harris and Secretary of State Antony Blinken.

“It is natural – indeed it is understandable – for some to greet any new call for American global engagement with ‘why us, why now, why there, why again’.”

“But the promise of America has never been fulfilled in isolation. The greatness of America has never been confined to your borders. And the people of Australia are not looking for a free ride.”

The very fact of Albanese’s state visit eased concerns that Biden’s administration could lose its focus on the Indo-Pacific because of its responsibilities in Ukraine and now Israel. White House National Security Council spokesman John Kirby promised securing peace and stability in the region was “right at the top of the list” of the President’s priorities.

“A great deal of the history of our world will be written in the Indo-Pacific in the coming years,” Biden himself declared at the state dinner held in Albanese’s honour.

“Australia and the United States must write that story together.”

While the event’s pomp and ceremony seemed incongruous to some Australian observers with what First Lady Jill Biden described as “tumultuous times” – even after the star power of the guest list was dimmed and music act The B-52s were grounded – it made more sense to Americans who expect their president to walk and chew gum at the same time.

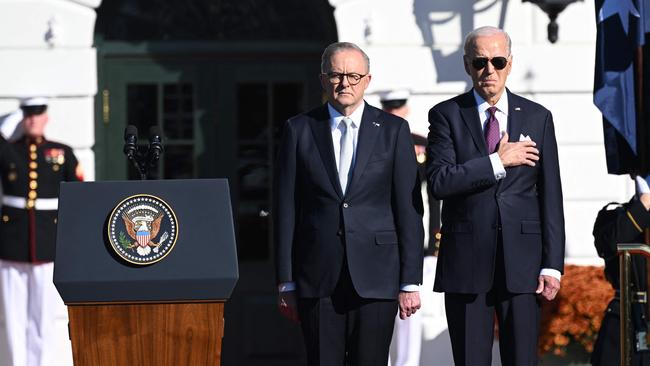

Albanese, who arrives home on Saturday, will present the trip as a great success. A state visit can have that effect on a leader: their country’s flag flies throughout the city; they are greeted by military bands and 19-gun salutes; they sleep at Blair House on Pennsylvania Avenue, the president’s guesthouse which is considered the world’s most exclusive hotel.

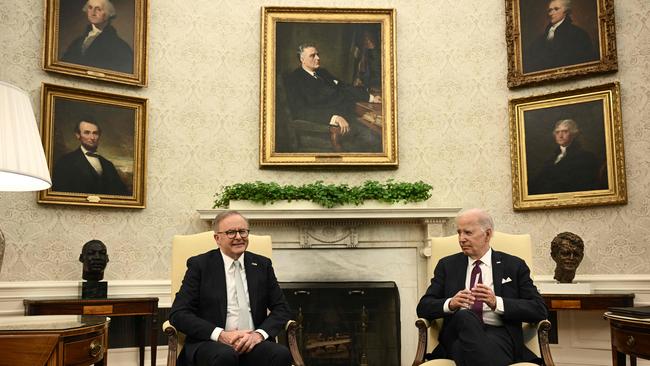

Occasionally, that sense of occasion overcame standard operating procedures. The Prime Minister waffled nervously to the President when journalists crammed into the Oval Office, and then his senior staff snapped selfies while waiting for the Rose Garden press conference.

But Albanese feels reassured by his obviously warm rapport with Biden, suggesting to a US reporter who wondered if America was a reliable ally that his relationship with the 80-year-old was “second to none” even among his domestic political colleagues.

During their ninth meeting in 17 months, Albanese peppered his remarks with the words of Biden’s favourite Irish poets and his son Beau, who died of brain cancer in 2015.

The President responded in kind and even wiped an insect off Albanese’s suit, although he put his foot in it by referring to “both of our wives”. (The PM and Jodie Haydon are unmarried.)

Whether the visit was a victory in substance as well as style, however, remains to be seen.

Albanese arrived with two priorities. One was co-operation on clean energy and critical minerals, and despite his government’s warnings that Biden’s hundreds of billions of dollars in green subsidies were sucking investment out of Australia, the US side offered no public indication it would change course.

The other priority was AUKUS, given the need for Congress to pass legislation allowing the sale of nuclear-powered submarines to Australia and repealing export controls that will otherwise continue to hamper the sharing of defence technology.

On that front, the most critical advancements had nothing to do with Albanese. Biden put $US3.4bn (A$5.3b) on the table to mollify those worried about the slow pace of submarine production, and then Republicans finally elected a new House Speaker, reopening the Congress after an unprecedented three-week paralysis.

While Australia has never attempted – let alone achieved – anything on the scale of acquiring nuclear submarines, United States Studies Centre chief and former senior White House official Michael Green pointed out before Albanese’s visit that “most of the US press corps doesn’t care about AUKUS”. The local coverage suggested he was right.

There is also some scepticism in Washington DC about Albanese’s commitment to the defence and diplomatic decisions needed to combat China’s rising aggression.

Hudson Institute senior fellow John Lee, who was the senior national security adviser to former Australian foreign minister Julie Bishop, says the “free-rider problem … justifiably concerns US lawmakers”, especially given the government’s sparse investment and slow pace of action in response to the urgency of its own Defence Strategic Review.

Charles Edel, the Australia chair at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, adds that there is “a feeling in Washington that Australia’s policy settings on Taiwan lag behind other American allies”.

And Biden himself, when asked about Albanese’s meeting with Xi Jinping next month, offered a message of caution about dealing with the Chinese President: “Trust, but verify.”

All in all, it is a reminder for the Prime Minister that it is too soon to be over the moon.

More Coverage

Originally published as Why Anthony Albanese can’t be over the moon after US trip