‘Cesspit of sin’: Dark side to Aussie tourist hotspot exposed

An Aussie has lifted the lid on the seedy underbelly of the nation’s new favourite holiday destination – and its wild night life.

World

Don't miss out on the headlines from World. Followed categories will be added to My News.

OPINION

Bottles and models. Ultra-rich salarymen. Velvet ropes.

Sounds glamorous, right? Wrong.

Because flick off the filter, and Tokyo’s model clubs can get ugly. That’s what I learnt when I uncovered a neon-lit underbelly of power on a working holiday I’ll never forget.

It’s a hidden side to the city that’s now the top Aussie tourist destination. A side that sells itself as a perfectly safe and welcoming wonderland. And despite turning it into an animated series and thriller novel, what I saw at that time was every bit as real as the bright lights these clubs lurk behind.

Take the self-confessed cannibal I observed plying underage girls with Belvedere. Or the yakuza owners I met, rumoured to use their venues as hunting grounds for trafficking models abroad. Or the Aussie model who flew to Tokyo in quest of adventure, never to fly home.

All right, I may be coming on a bit strong here. Let’s wind back to where it all kicked off.

It’s January 2009, and I’m in the least fashionable place imaginable: the Big Day Out Boiler Room. For those on TikTok, the Big Day Out was Australia’s sweatiest music festival, held annually at January’s peak, and the Boiler Room was its armpit. An indoor EDM sweatshop.

During Prodigy’s set that year it started ‘rave raining’; a weather phenomenon where it’s so hot the crowd’s sweat condensates on the roof and drips back down from whence it came.

You can imagine my confusion then, when a baby-faced woman asked if I was signed, and flashed her card. My mates were sure it was a scam. I was less model material, more Mr Bean, they explained.

But after a few weeks, I pulled out the sweat-crinkled card. Curiosity got the better of me; the idea of getting whisked around the world earning the big bucks. It was more than I could knock back. Looking back, I’m grateful at least one of those things happened.

So after some onboarding (practising sucking in my cheeks), I signed the papers and packed my bags. Next stop: the Land of the Rising Sun.

While supermodels fly to Milan or Paris to be seen, catalogue models like me go to Asia to disappear. In these markets, white models are in higher demand. That suited me: I wanted to see something new, and had long loved all things Japanese. I didn’t need to be the best mannequin.

The day before my departure, I shed my last expectations of a red-carpet arrival when my Sydney booker instructed me to lie to Japanese customs. By telling them I was here on a holiday, I could work under-the-table on a tourist visa. Later, I learnt I could have been locked up for breaking foreign labour laws. The scheme is about more than just cutting costs: with no access to legal labour protection, models are easy to exploit.

Luckily, I slipped past with my portfolio of photographs undetected, to be greeted gateside of Narita Airport by my driver, a cheery fellow with a sad smile. In Japan, foreign models are chauffeured around. It’s less a luxury, more an assumption we’re too dumb to navigate Tokyo’s confusing streets.

I was given a burner phone and weekly allowance. Enough for instant ramen and the odd vending machine Suntory Strong. While we’re on the topic, the finances were misty. Once I started working I had no idea how much I was getting paid, or how much my flights, accommodation and cash advances took out of that. In the end, I didn’t leave with a dollar. But it was Monopoly money anyway. And with their luck in the genetic lottery, it’s not lost on me that models aren’t the most sympathetic characters. We were lucky to be there, for sure. That doesn’t negate their workplace rights, though.

That night, we made our way through the dense crowds of Shibuya Crossing to a cute coffin apartment overlooking Shibuya Station’s packed platforms.

Next morning, I fell into the routine. Long days spent either in the van going to or from castings, or behind the camera shooting never-ending catalogues. The atmosphere in the van was like a school bus, goofing around with the other models. And the shoots were mindless fun, if you channelled Lost in Translation’s Bill Murray.

Then one night, I got a text from a random number.

“Last chance for tonight”.

There’s no history under the number. Was it my booker, using another phone? An organ trafficker, keen for my kidneys? Either way, I was broke, bored and hungry. Easy prey.

“What’s tonight?” I sent.

“Jumanji”.

Jumanji was a “bottles and models” club, which meant this was a promoter. It was their job to lure models to the club, which in turn lured salarymen. That’s who bankrolls the bottles, in exchange for the models’ company. Sure, some of them were a bit seedy. But couldn’t I handle a few bald heads for a free night out?

That what I told myself on the walk to Tokyo’s red-light district of Roppongi. It’s a cesspit of sin that comes undead after dark. Down a dark alley, up a staircase flanked by demonic statues, to a tiny door girl enthroned behind a desk. She looked me up and down then fastened a gold band over my wrist. This means my drinks would be on the house. No ID needed.

When I reached the cluster of foreign models sipping drinks poured from a bottle of Belvedere lodged in a golden ice bucket, I discovered why this was prickly. Some models were young: dangerously young. Unlike the salarymen, a sorry looking lot of bald men circling the booth like bull sharks. One bridge troll of a man caught my eye.

“Who’s that?” I asked the promoter, a fella wearing shiny shades who might have escaped the set of Jersey Shore.

“You don’t wanna know.”

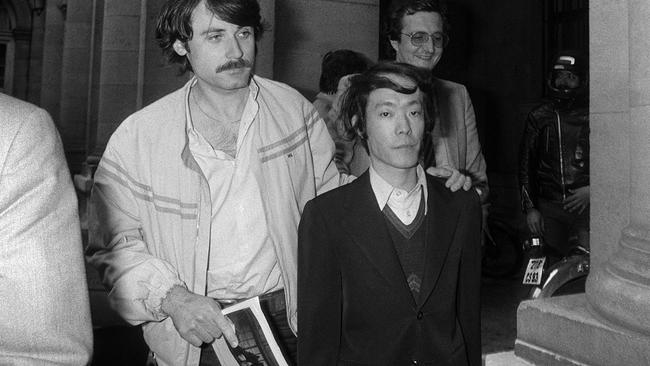

Another model dished the dirt: it was Issei Sagawa. Aka the “Kobe Cannibal”.

In 1981, Sagawa raped, killed, then consumed parts of a young woman and fellow student in Paris. A French court found him insane and deported him back to Japan, where he was protected by his wealthy mogul father. Sagawa became a predator of Roppongi, prowling clubs like this for young white women until his death from natural causes in 2022.

“Why’s he here?” I asked.

“Us”.

I wanted to kick this goblin to kerb. But like Attenborough observing a predator in the wild, I was powerless to interfere in the course of nature.

At first glance, there was little remarkable about the venue. DJ spinning the same radio songs in a booth. The smell of clashing colognes thick in the air. Dance floor bursting with gyrating bodies. Many of them looked like civilians, foreign teachers and bankers. But look a little closer, and you saw a little more.

That night, the promoter introduced me to the owners, a group of blokes in baggy suits looking over the room with stony eyes. The first thing you noticed was their eyes. Holes. Even when they smiled, there was nothing in them. Then I noticed the tatts. Even in suits I could see they’re all densely decorated, dragons sloping around their arms and necks, coming to life with every movement. Yakuza.

Like a moth to a flame, I felt drawn to this danger. Back then, the yakuza were stakeholders in Tokyo’s economy and Roppongi was completely under their rule. Coming from the land of Nike Bikies, there’s something positively exotic about the Japanese mafia.

One night, I skolled sake with the owners at the bar, bridging the gulf of language and culture. It’s important to note that it was easier for me to get away with this than the female models. As a male, my body wasn’t a yakuza commodity.

For so long, yakuza were considered chivalrous in Japanese society. People turned a blind eye to their trail of terror in the belief they kept the streets in check. Human trafficking was key to this terror. Rumours swirled of models abducted in these clubs and sold in the Middle East. But human trafficking is a shadowy business run by powerful people. It’s hard to pin down.

The owners look the other way, making the clubs lawless. If something happened, we had nowhere to turn. Especially under our sketchy working arrangements. At that moment in history, these men seemed almost untouchable.

But just months later, when I’d returned to the place I called home, police cracked down on them with a raft of anti-yakuza laws, slashing their numbers and power in Japan.

In no way are bottles and models clubs unique to Japan. I would later go to similar establishments in Hong Kong, London and New York. But there was something uniquely insidious about the Tokyo scene.

Because I’d heard these clubs hide a dirty secret – extra services from the models. There were degrees of depravity, from dates to much more. To me, it was all an exchange of women’s bodies for money – the promoters, flesh-peddling pimps. (I’m not implicating anyone pictured).

There were nights you would see young girls sipping cocktails with men old enough to be their grandfather. Some of these girls came from disadvantaged backgrounds, and the opportunity for a brighter future seemed worth the risk.

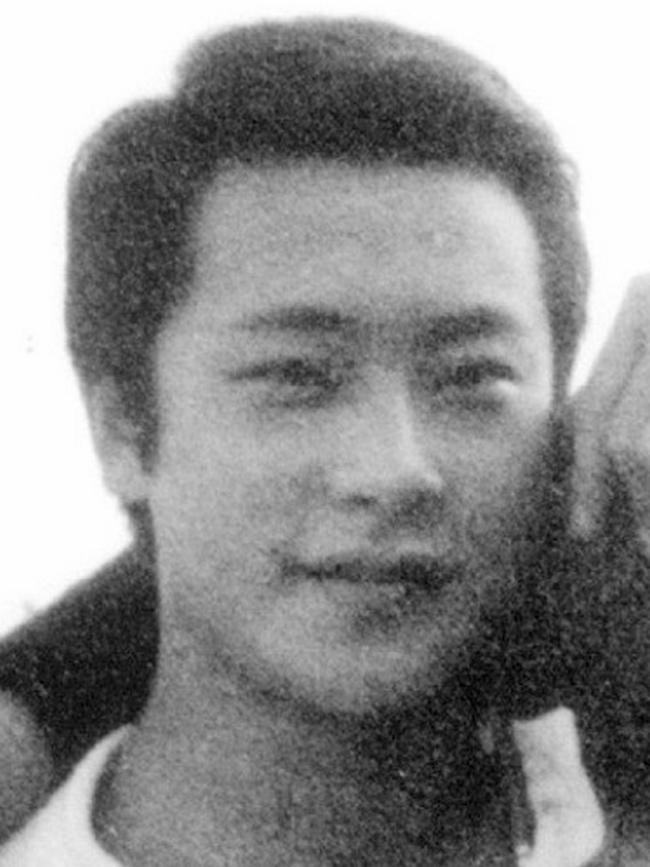

Such opportunities could come with a human toll. Carita Ridgway was 21 when she came from Sydney to Japan in 1991. The model was not coming under contract with an agency. Rather, she was drawn to Tokyo by the prospect of lucrative holiday work in its night life.

She was working in a Roppongi nightclub the night she met Joji Obara, a charming property tycoon who invited her to his seaside apartment in Miura. It was here she was drugged, raped and killed.

For years, police took little interest. Until in 2001, when an international investigation uncovered the dismembered remains of another young woman, Lucie Blackman, in a shallow grave less than 100 metres from the same apartments.

Both cases were explored in the recent Netflix doco Missing: The Lucie Blackman Case. Obara was later found to have raped between 150 and 400 women, and is currently serving a life sentence behind bars.

I didn’t learn about these tragedies until I’d left Tokyo. Knowing then would have cast my trip under an even darker shadow. But it’s important to look at the bigger picture.

Japan still ranks very low globally for rates of violent crime, and it remains one of the world’s safest destinations for women. Cliches about Japanese men’s obsession with foreign women aren’t helpful.

Even at the time, I knew what I’d gotten a glimpse of was rare. A watering hole of cannibals, gangsters and models drinking together in the wild. Hiding down a back alley in one of Tokyo’s busiest districts. That’s why I was inspired to write my upcoming novel, The Auction, and its animated series. It was a tale you wouldn’t find in Lonely Planet.

After my first night in Jumanji, the rest of the routine fell out of focus. I got through the castings, drives and shoots. It all felt like a distraction before I could get back in the club. I picked the brain of its promoters, owners and models, knowing I would one day tell this tale.

You might wonder: why fictionalise such an already unbelievable tale? But the story that spoke to me was the possibility of the club’s connection to something bigger. I won’t give the game away. You’ll have to buy the book.

In no way do I wish to warn you against visiting Japan. It’s place as the top pick for Aussie tourists is well justified. Nor do I want to spook fun-seekers away from venues like Jumanji, which is pouring bottles and pulling models to this day. I’m just reminding you to stay smart.

Tokyo may be the city of lights. Though you’d be wise when you’re there not to switch off your wits.

Nelson Groom is a freelance writer. His novel The Auction is coming soon. Learn more on Nelson’s Instagram here

Originally published as ‘Cesspit of sin’: Dark side to Aussie tourist hotspot exposed