Why Indigenous AFL star Shaun Burgoyne feels footy, and he, let down Adam Goodes

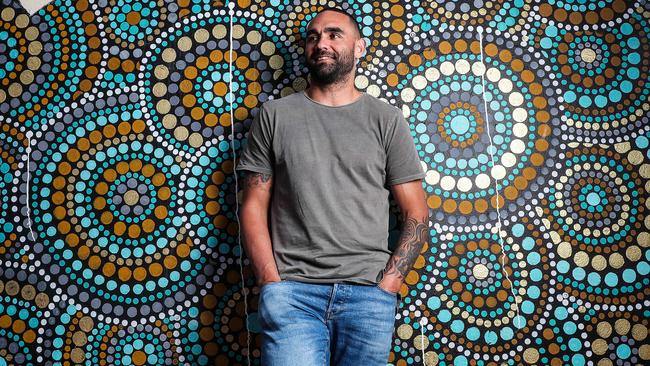

AFL 400-gamer Shaun ‘Silk’ Burgoyne still burns with a sense of shame remembering how Adam Goodes was booed. One of his biggest regrets is not publicly supporting his mate earlier.

Victoria

Don't miss out on the headlines from Victoria. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Shaun Burgoyne was decidedly uneasy as his 400th AFL game approached. He doesn’t like being the centre of attention.

He was photographed with the four other players who have achieved the milestone, from Kevin Bartlett to Brent Harvey.

Burgoyne was rightly placed in the middle of the Marvel Stadium shot, the new member of the exclusive club. Goodwill flowed, from Patty Mills to Cathy Freeman, but Burgoyne didn’t feel like he belonged. As he puts it now, a few months later: “They’re icons of the game. And I’m not. I consider them legends and I don’t see myself in that way one single bit”.

Most football fans would respectfully disagree. As his former coach, Alistair Clarkson, says, Burgoyne is an icon. A trailblazer. A role model. And “such a humble person”.

Burgoyne’s nickname of Silk goes to his poise under pressure; those clutch choices when his composure in chaos turned quarters and games his team’s way.

A big player for the big moments, Burgoyne won four flags, at Port Adelaide and Hawthorn, in a 21-year career he calls “hanging on for dear life”.

Near the end, Burgoyne, at 38, would line up against players half his age. The physical journey, especially in the final years, was hobbled by ruptures and strains.

Hub life cast off the anchors of his football being. “One of the keys to my success in playing so long was routine and having a stable home life and family life and football life,” he says.

“It was a challenge to change all that up in the last two years. I’m very routined. I don’t like change.”

Yet the biggest shift of his adult life has, so far, been kind. In retirement, Burgoyne and his family have moved back to Adelaide, for him to work in football operations at Port Adelaide.

He does not miss the intense scrutiny of what he ate and how he trained. “That mental load has just lifted off me,” he says. “I don’t feel like I have to worry about any expectations.”

Burgoyne is acclimatising to a role he now feels he can provide. As football coach Mark Choco Williams has said, Burgoyne’s potential for off-field accomplishments – whether in politics, advocacy or business – promises more than the on-field glories.

Williams looks forward to hearing from the ex-footballer “who stands up for his people but also for what is right”.

Burgoyne has already reduced football to a (rather big) subplot in a bigger tale.

Of his new book, Silk, Burgoyne speaks of rejecting proposals to write it again and again. Its release prompts similar anxiety he felt in the celebration of his breaking Adam Goodes’ Indigenous record for the most number of games played.

His poise for speaking in public has taken decades to seed and flourish. Burgoyne is and always will be a “shy kid” from the bush.

But he has been emboldened by necessity. If the lessons of Indigenous disadvantage are still being learnt, Burgoyne wants to shape how they are taught.

Goodes – and his principled stand against racism – features heavily in Burgoyne’s odyssey of Indigenous awareness and advocacy.

Burgoyne writes about Hawthorn losing a thriller to the Sydney Swans in May 2015. A grand final replay, Sydney upturned the 2014 result.

But Burgoyne doesn’t recount the scores that day. Instead, he still burns with a sense of shame for each time Goodes got the ball, when many Hawthorn fans reflexively booed the Sydney great.

‘We let Goodes down … he’s a very courageous man’

Burgoyne has spoken to other Indigenous players throughout the league from that period. They shared his extreme discomfort. Burgoyne has a simple explanation for the booing – racism.

He blames himself in part for the belated response to the treatment of Goodes. He wasn’t loud enough – or fast enough – to address the wider injustice which ultimately pushed Goodes from the game.

Burgoyne was younger, less certain of his place. “We let him down,” he says of a good mate. “He’s a very courageous man. He took a stand and we should all applaud people like that and stand beside them, not behind them. I think as an industry we dropped the ball in supporting Adam straight away and I was part of that.”

Burgoyne’s wider advocacy for Indigenous issues – his insistence that lessons must be learnt, and that the best response to racism demands that non-Indigenous Australians take a stand against it – stems from such realisations.

There have been many. Such as the time when a Port Adelaide change-room comment about a supposed “black versus white” division became big news. Or his recognition that Australia Day was an appalling commemoration of Indigenous history.

Burgoyne was a founding member of the AFL Players Association Indigenous Advisory Board in 2011. The average span of an Indigenous player in the AFL was four years. Problems of relocation, lack of support and loss of identity would be addressed.

Burgoyne eschews fiery rhetoric. His tone is conciliatory. He doesn’t seek to blame. Rather than condemn the idiot fan who threw a banana, he prefers to admire the response of Eddie Betts. He bows to the examples of Nicky Winmar and Michael Long.

Burgoyne talks more of learning from as opposed to righting past wrongs. If he was “more than disappointed” by a racist remark of Adelaide Crows player Tex Walker, he also envisages positives from a “pretty big negative”.

When Burgoyne gives talks in schools, kids offer blank stares when he asks them the colours of the Aboriginal flag, or for the name of Eddie Mabo.

“It just goes to show that the education system is not really teaching kids Indigenous history to the extent that it should be taught,” he says. “Some schools don’t even teach Indigenous history. We don’t really learn about our own country.”

Burgoyne is buoyed by his involvement in an Indigenous cleaning business. It’s a small start, he says, but Indigenous employment is a wonderful launch pad for bigger projects.

“I thought if we’re going to close the gap and create better outcomes and all those things why not start with employment opportunities,” he says.

Burgoyne is imbued with an innate humility. He credits his sporting longevity to the cocoon of family love, from his wife and teenage sweetheart Amy to their four kids.

He and Amy have been partners since year 10. Her Phillips pedigree – both her sister and father played elite footy – armed her with an understanding of footballing travails.

Amy and the kids would gather to giggle when Burgoyne prepared his honey sandwich in what was a pre-game ritual. The couple still laughs around the kitchen table about her describing Burgoyne’s confidence in being drafted to the AFL in 2000 as a bad case of “big-noting”.

Footy was a job, he now says, albeit all consuming. Fatherhood is something grander, a bigger accomplishment.

His children – Ky, Percy, Leni and Nixie — have been fixtures in his public sporting life. They have draped themselves on grand final trophies and chatted with players throughout their lives.

They would join in his Sunday recovery sessions and especially enjoyed the ice baths and spa.

“What I like to do is create memories and hopefully one day when my kids have their kids and they have grandkids they can say well we used to go with Pop or with Dad to training,” he says. “Those memories for me are what I cherish most.”

His was a happy childhood in Port Lincoln, an unusual hive of ethnicities and demographics. The fishing industry was split into the very wealthy and rather poor.

Fishing for squid off the jetty was spliced with camping, cricket and, of course, football, which was played in the driveway.

His father, Peter Sr, is a Kokatha man. His mother, Gabriella, comes from the Warai people south of Darwin.

Peter Sr had played a handful of games in the SANFL before returning to friends and family in the bush. His talent is widely lauded to this day, yet he felt isolated in the city.

Shaun, like older brother Peter (they later played together in Port Adelaide’s 2004 premiership team), played against kids many years older in under-age matches.

Sport was the ticket from trouble, the great leveller.

Burgoyne’s approach to fatherhood nods to his own upbringing. “We saw our uncles and older cousins played footy and we just wanted to replicate what they were doing,” he says.

Burgoyne received plenty of racist taunts as a kid. He recalls an older Anglo-Saxon kid who took exception to his sitting at the back of the bus for a school aths competition. There was racist graffiti at school.

‘Hopefully I can continue to influence lives’

Burgoyne learnt to hold the anger in, after being punished for physical retaliation. He felt judged from the start, and looked down upon for his skin colour.

But he didn’t question a wider society that allowed such behaviour to flourish.

“As a kid growing up you probably didn’t have the tools or the courage to stand up,” he says. “Hopefully kids coming through now can see we’re in a different Australia, a multicultural Australia, a country that is improving in this area.”

As Burgoyne says, his kids are his greatest motivation. “I want my children to grow up a bit differently to me,” he says, “and not go through some of the things that I went through.”

This shy kid has more to do. The past will fuel the future, he hopes, though is he isn’t saying — or doesn’t know — where it will lead.

It could be politics. It could be advocacy. But he grasps that his footballing end is a misplaced way of describing a bigger beginning.

He knows there is more than the “big platform” of football. “Hopefully I’ve used my (sporting) profile to influence lives,” he says.

“For the next step after football, hopefully I can continue to influence lives.”

Originally published as Why Indigenous AFL star Shaun Burgoyne feels footy, and he, let down Adam Goodes