Rare second chance to see French Impressionism masterpieces in Melbourne

Masterpieces by Monet, Renoir and Degas are back in Melbourne, four years after the pandemic denied thousands of people an opportunity to to see them. Find out how the NGV got them back.

Victoria

Don't miss out on the headlines from Victoria. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Immediately after the National Gallery of Victoria was forced to close its French Impressionism exhibition prematurely in 2021, negotiations began to get it back.

About 60,000 people had flocked to the Melbourne gallery to see the 100-odd masterpieces loaned from Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts – which included Monets, Renoirs and a van Gogh – before the Covid pandemic shut the exhibition down within just 30 days.

Luckily for Australian art lovers, the institutions’ directors – the NGV’s Tony Ellwood and MFA’s Matthew Teitelbaum – agreed this was nowhere near enough.

“Both sides said, ‘We can’t let this be the one that got away’,” recalls NGV senior curator Dr Ted Gott.

“We got (the exhibition) in the first place because, at that time, Boston was renovating the galleries where they hold their Impressionist works. So it’s quite incredible that, although those renovations are finished, they’ve agreed to lend it to us again.

“So many of the paintings in the show are just iconic. I’m sure there will be visitors in Boston who are upset that Renoir’s Dance at Bougival is not there, it’s in bloody Melbourne!”

The rare second chance to see “one of the world’s best French Impressionist collections” opens at the NGV on June 6.

The 2025 version will retain key drawcards from the 2021 iteration – notably, a spectacular “show me the Monets” moment: one room containing 16 canvases painted over 30 years by the most famous Impressionist, making for a grand finale to the exhibition.

It will also feature a handful of additional artworks, and present them in a much more ornate setting than the plain white walls from four years ago. The NGV has engaged specialist tradies from across Victoria to recreate the interiors of 19th-century mansions where the Bostonians who originally owned the works displayed them before they, or their families, bequeathed them to the MFA.

“There will there will be fabrics, floorboards, curtains, chandeliers, furniture,” Gott says. “(Visitors) will see great paintings in this gorgeous, tactile environment.”

If previous Impressionist exhibits are anything to go by, it’s sure to be a hit.

The gallery’s inaugural Melbourne Winter Masterpieces show – 2004’s The Impressionists: Masterpieces from the Musée d’Orsay – attracted a then-record 380,234 visitors. In 2013, more than 342,000 people experienced the gallery’s Monet’s Garden exhibition.

The 2025 iteration of French Impressionism will also open off the back of the NGV’s biggest ever hit, Yayoi Kusama – which drew 570,537 art lovers to smash the previous benchmark (held by Van Gogh and the Seasons since 2017) by more than 100,000 visitors.

MFA Boston curator Dr Katie Hanson says part of Impressionism’s enduring appeal is that the artists “picked their here and now as being worthy of art”. This included capturing their favourite European landscapes – a relatable practice for modern-day tourists.

“They’re not looking to ancient history, literature or religion or anything outside of themselves and their environment for their subject matters,” Hanson says.

Gott agrees these paintings are “perennially popular” because viewers “don’t have to know about Greek mythology or Roman history or religious paraphernalia” to enjoy them.

“You just can say, ‘Wow, look at that incredible haystack under the snow, or that field of poppies, or that gorgeous couple dancing in an outdoor beer hall’,” he says.

“They are fabulously consumable, and there’s absolutely nothing wrong with that.”

Impressionism hasn’t always been viewed this way – in fact, the movement started “with an insult”.

Its name derives from a damning review, from critic Louis Leroy, of Claude Monet’s 1872 painting Impression, Sunrise.

Leroy described it as “barely an impression of a finished painting”, Gott says: “The artists grabbed the insult and wore it as a badge of pride.”

He adds that people attended the first ever Impressionism exhibition in 1874 “just to laugh” at it. This reaction is reflected in cartoons from the time, including one depicting a man in a top hat pulling a painting away from the wall.

“A guard says, ‘Excuse me, sir, what are you doing?’ And he says, ‘I’ve heard that these Impressionists have talent, I’m just checking if this picture hasn’t been hung back to front’,” Gott says. “It’s brutal.”

Nineteenth-century audiences simply “did not know what they were looking at”, he says: “At the time, these paintings were so incredibly radical. Now we appreciate them as beautiful, but it was a tough slog for the poor old Impressionists at first.”

Even artists within the movement squabbled about who belonged, and who didn’t.

Camille Pissarro was rejected by some Impressionists for being “too politically engaged” as a supporter of communism and anarchism, Gott says. Edgar Degas was adamant he was “not an Impressionist (but) a realist”. Neo-Impressionists – like Paul Signac, whose Gasometers at Clichy painting will feature in the NGV exhibition – “horrified” many Impressionists for being “too mathematical and scientific in their approach”.

Gott explains that Impressionism was ultimately about “freedom”, which meant “there was no one type of Impressionist painting”.

“You can’t mistake a Renoir for a Monet,” he says.

“The artists were all determined to break away from the rigid rules that artists prior to them had been forced to go through.

“They put colour straight on to raw canvases (and) used bright colours, often squeezing them directly out of the tube. They made it a badge of pride to show their brushstrokes.”

American collectors in the late 19th and early 20th-centuries were more open to Impressionist art. Hanson says this is part of the reason the MFA boasts one of the world’s richest holdings of paintings from this movement.

“Bostonians were buying Impressionism while the paint was still wet,” she says.

“We’re the lucky beneficiaries of those collectors with such foresight, but also such determination that they were going to buy what they liked.”

She adds there are many “charming stories” of collectors travelling from Boston to France to buy these avant-garde works – from newlyweds “spending their honeymoon money on a Monet” (1891 work Grainstack, snow effect, which will be on show at the NGV) to those “haggling with Paul Durand-Ruel, an art dealer in Paris, over the price of a picture they want for their for their home in Boston”.

The NGV and MFA have developed an “unusual Impressionism exhibition”, Gott says, because it also shows where the movement came from, and where it went.

It features works from the Barbizon School of painters, active prior to the Impressionist period from about 1830-70, which are rarely exhibited in Australia. This includes Eugène Boudin, who discovered a teenage Monet “doing caricature sketches in a restaurant” on the Normandy coast in the 1850s and immediately recognised his talent.

There are also pieces by Édouard Manet, who was considered a crucial figure in the development of Impressionism, but never explicitly joined the movement.

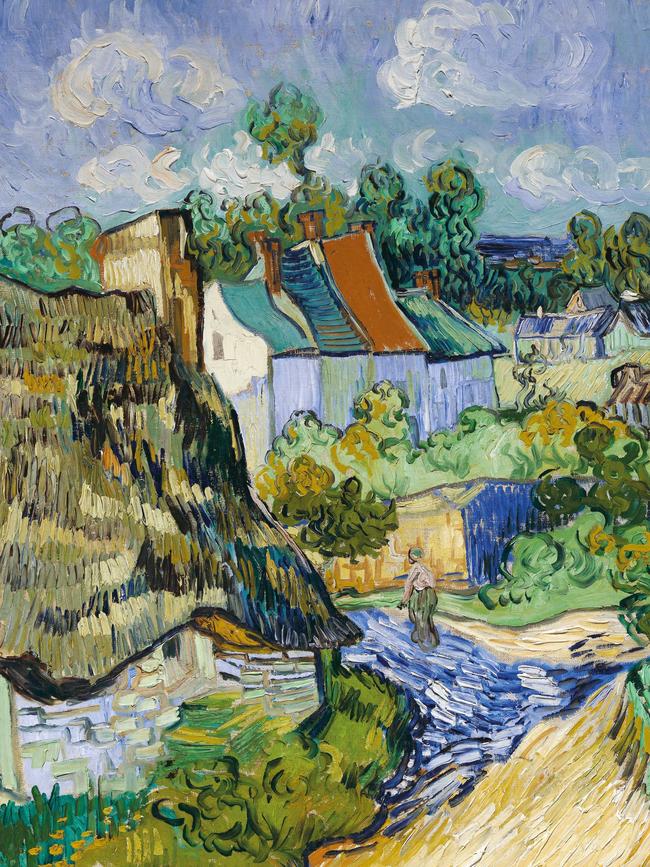

Famous artists who were influenced by Impressionism – notably Vincent van Gogh and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who became known for his association with the Moulin Rouge – are represented in the exhibition, too.

Hanson says while world-famous Impressionist works have been “reproduced on calendars and coffee mugs and sweatshirts”, there’s nothing like seeing them in the flesh.

Take Dance at Bougival – an undisputed highlight of the exhibition that transports viewers to the time and place Renoir captures.

“There are discarded cigarette butts, a bouquet of flowers, partially drunk beers in the background. We assume there’s music,” she says.

“The hands and the faces of the (dancing) figures are either touching or so close that you really get all five senses with the painting, if you open yourself to all the possibilities it suggests.”

The artworks will take visitors on a European holiday during Melbourne winter – across France to places like Paris and the nearby Fontainebleau Forest, Pontoise, Giverny and the Normandy and Mediterranean coasts, and over to Venice, Holland and Guernsey.

The Monet room reflects the artist’s travels on “yearly campaigns”, aimed at ensuring his work was fresh enough to attract buyers – and help keep a roof over the heads of himself, his wife and the eight children they shared.

Gott says the arrival of Bostonian collectors ensured Monet “suddenly sold everything he painted” and was ultimately able to buy his house in Giverny and later, the adjacent property where he created his world-famous garden.

“It’s incredible to be able to spin round in this circular room and just see 16 Monets,” Gott says. “If that’s all that was here, people would still come. But that’s just the finale of a mind-blowing exhibition.”

See French Impressionism at NGV International from June 6 to October 5. ngv.vic.gov.au

French Impressionism: works you won’t want to miss according to …

MFA Boston curator Katie Hanson

Dance at Bougival by Pierre‐Auguste Renoir

Renoir evokes “all our senses” in this joyful painting, Hanson says – those who fully immerse themselves can almost hear the music playing, smell “discarded cigarette butts (and a) bouquet of flowers”, taste the “partially drunk beers” and feel the dancers’ touch.

Depictions of Victorine Meurent: Self-portrait by Meurent, portrait and Street Singer by Édouard Manet

“Jill of all trades” Meurent was Manet’s favourite model, a former cancan dancer and an artist in her own right, and Hanson says these three works reflect several different sides of her. The self-portrait is notably a new addition to the exhibition since it was last here in 2021.

Abbeville and River view by Frits Thaulow

Thaulow’s works are a “surprise” hit of the exhibition, Hanson says, noting the Norwegian artist and friend of Monet “paints the like rippling surface of water so beautifully”.

NGV curator Ted Gott

Grand Canal Venice by Pierre‐Auguste Renoir

A product of Renoir’s travels to Venice and Florence in 1881, to “study the works of Leonardo, Raphael and Michelangelo” and advance his own paintings, Gott considers this “one of my favourite works in the show”.

Edge of the Woods (Plain of Barbizon near Fontainebleau) by Théodore Rousseau

For Gott, this painting evokes “a great story about artists not only loving nature, but (getting) large parts of it saved”. Rousseau convinced Emperor Napoleon to declare Fontainebleau “the world’s first national park – saving it at a time when trees were being felled and stone being quarried to build Baron Haussmann’s Paris”.

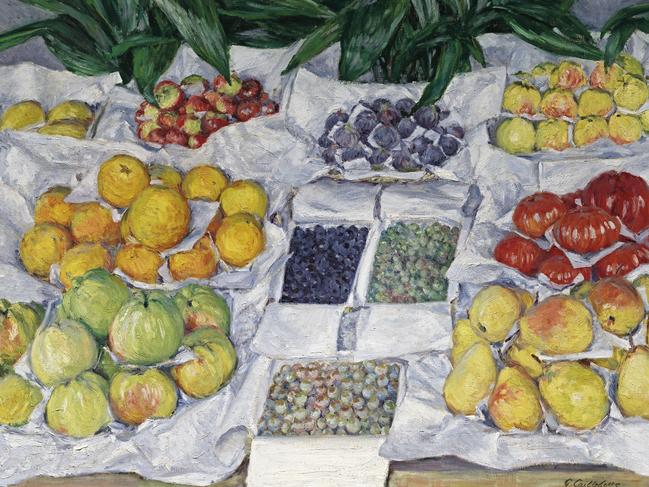

Fruit displayed on a stand by Gustave Caillebotte

This work reflects its “millionaire” painter’s wealth, Gott says: “(Poorer Impressionists) Renoir, Monet and Pissarro could not relate to (this painting’s subject) because Caillebotte is showing a high-end fruit display … in a very wealthy part of Paris. Each piece of fruit is individually wrapped, sitting on a little piece of tissue paper.”

Garlic seller by Jean‐François Raffaëlli

Another new addition to the exhibition, this painting is a standout by little-known artist Raffaëlli – a close friend of Degas who documented “the hardship that was behind the glamour” of Paris.

Originally published as Rare second chance to see French Impressionism masterpieces in Melbourne