Meet the 32-year-old running a multimillion-dollar farming empire

James Paterson’s farming empire spans 67,000 hectares across 11 properties in Victoria’s Western District and the NSW Riverina. This is how he does it.

Victoria

Don't miss out on the headlines from Victoria. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A worn pair of runners caked with cow dung said a lot about the late Gordon Paterson, patriarch of one of southern Australia’s biggest farming empires.

The pastoral icon, who died in September aged 88, would don the unconventional footwear to work in the cattle yards, as part of a “why walk when you can run” mantra.

That motto has landed squarely on the shoulders of his grandson, James, thrown into the multimillion-dollar JHW Paterson and Son business in 2012 aged 20, but has served to create a multi-pronged, highly efficient quasi corporate operation run with an overarching family philosophy of respect.

The Paterson empire spans 67,000 hectares across 11 properties in Victoria’s Western District and the NSW western Riverina, growing 12,000 hectares of crops including cotton, running 6500 breeding cows and operating a state-of-the-art feedlot, with capacity for 25,000 cattle, churning out quality beef week after week to growing global demand.

When Gordon’s son and James’s father, Lachlan, died of motor-neurone disease in 2008, the business was at a crossroads. Gordon was in his early 70s, ready to step back and hand over the reins but the tragic passing was something no one saw coming.

That James was going to return as the fourth-generation Paterson to run the business was not a question of if, but when.

“I had dreams of working in the Northern Territory or Queensland after I’d finished school in Melbourne,” says James, now 32.

Instead he was thrust into a unique working relationship with his grandfather that has created enviable business growth in the fickle world of agriculture.

To an outsider, it may have appeared James had landed on his feet, being young and part of a business that had a healthy appetite to risk and a desire to make the most of opportunities.

What that view didn’t take into account was James’s age, the much-older staff he would be managing at the same time as mourning not only his father, but his dreams of a northern adventure.

Speak with James now and there’s never a sense of regret, more an acknowledgment of what happened, and a mature willingness to accept the hand he was dealt.

“I’d grown up at Hells Gate (the jewel in the Paterson crown near Balranald in NSW) and had always helped and been part of it, but it wasn’t for fun anymore – things were serious now,” he says.

PROUD HISTORY

Named for James’s great-grandfather, John Hector William Paterson, JHW Paterson and Son was founded initially as a beef business in Victoria with a small property near Yanakie in South Gippsland and a leasehold on nearby Wilsons Promontory.

The operation later expanded north with the acquisition of smaller holdings around Swan Hill, before its first major purchase of the famed Hells Gate property, on the vast open Riverina plains between Balranald and Hay, in the 1960s.

Nowadays, the Paterson footprint extends across 10,000 hectares of Victoria’s Western District and 57,000 hectares of the Riverina, including Hells Gate, Loorica near Balranald (added in the mid-1980s) and Berawinnia at Maude, purchased in the early 1990s.

The family’s Western District venture started in the mid-1990s with the purchase of the 1634-hectare Vermont property between Penshurst and Macarthur.

The southern portfolio now also includes Iramoo, between Darlington and Camperdown, purchased in the early 2000s, Clifton, between Anakie and Geelong, added in 2005, Kurrambee at Cavendish, purchased in 2015, and Glenlevitt near Hawkesdale, added in 2018.

The Western District properties are home to an Angus and Wagyu-infused breeding herd, the progeny of which are trucked to the Riverina and grown out to 350kg liveweight, before entering the Hells Gate feedlot – one of the first on-farm feedlots in NSW, established in the 1970s.

The feedlot is an impressive example of vertical integration and risk management, allowing for guaranteed supply and beef contracts to be issued even before any cattle have been mated.

The cattle are finished at a range of weights with a portion producing a hefty carcass of 450 kilograms. Recently, in an effort to diversify away from purely first-cross Wagyu, a short-fed 100-day program involving British-bred cattle has also been introduced.

The geographical spread of the Paterson country might not be surprising, but what is, James concedes, is how it played out this year.

“You wouldn’t really think that having country between Hay and Balranald would offer relief to normally high-rainfall country in the Western District, but it has,” he says, acknowledging the tough conditions in southwest Victoria which recorded its driest start to the year on record.

“It has meant we will be able to cut hay this year down south because we’ve been able to relieve the grazing pressure down there.”

LEADERS OF THE PACK

Trailblazing, innovation and seizing opportunities are traits that seem to be in-built in the Paterson family genes. In the mid to late 1990s, Gordon was a regular visitor to the NSW Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area where his appetite was not for the region’s wines or renowned fine Italian food, but for high-security water entitlements.

At the time, many of the horticultural farms in the region had more than enough water to irrigate their crops, and local grape and citrus growers saw the chance to make money by selling their excess.

Gordon swooped in and, bit-by-bit, put together an enviable portfolio of high-security water – the most reliable allocation on the Murrumbidgee River that gets first dibs on water held in Blowering and Burrinjuck storage dams.

It would prove a masterstroke.

The water was used initially to grow pastures to breed cattle to go into the feedlot, essentially drought-proofing the western Riverina properties that boasted an annual rainfall average of 250-275mm.

However, when doing the sums with their long-time family accountant Peter Cramer, James and Gordon didn’t like what they were seeing.

“When you looked at the value of the water, we needed to work out the best return on a gross margin basis and it wasn’t growing pastures for cattle,” James says.

“We looked for the best gross margin for that water, and the figures came up with cotton.”

Spurred on by new varieties that allowed its production away from its more northern climes, the family began a foray into cotton, converting irrigation bays to row cropping in a massive revamp of their country.

TRIAL AND ERROR

In its first year in 2012, JHW Paterson grew 130 hectares of cotton which yielded eight bales a hectare, not exciting by industry standards but not a disaster either.

James loved cotton, and the challenges and excitement of starting a new project, and Gordon, who could see it made sense financially, became a convert.

“Grandpa said I needed to learn how to control the spending but at the same time, he understood that things needed to be done on time to be successful, and that meant a big capital outlay on machinery – we couldn’t rely on contractors who may or may not get there on time,” James says.

“I remember once timing was an issue and we needed another tractor and he said ‘Just go out and buy it’. Despite himself, Grandpa enjoyed cotton, even to the point of learning about forward selling and signing up for a price for a crop that wasn’t even planted yet.”

Expanding the cotton enterprise was also a move to offset risk. James says the 2022 outbreak of foot and mouth disease on Australia’s northern doorstep in Indonesia had highlighted the business’s exposure to cattle.

That same year, the Patersons upped the cotton stakes when they purchased the neighbouring 20,000-hectare Kooba Ag aggregation, southwest of Hay, for $63 million.

James, who cheerfully admits he failed accounting at school but has a healthy appreciation and knowledge of figures and the backup of good accountants, had crunched the numbers.

“I knew the ‘worst’ cotton crop we had grown was eight bales a hectare so we budgeted on that, and we had a shocking, cold season and we got five bales a hectare,” he says.

“Our purchase strategy, using interest-only loans, is successful when there are increases in property values, and at the time when the cotton crop came in under budget, property values also plateaued, so it put a bit of pressure on the business.

“But the next year, we grew 13 bales a hectare – and we were away again.”

‘HE WEARS STRESS WELL’

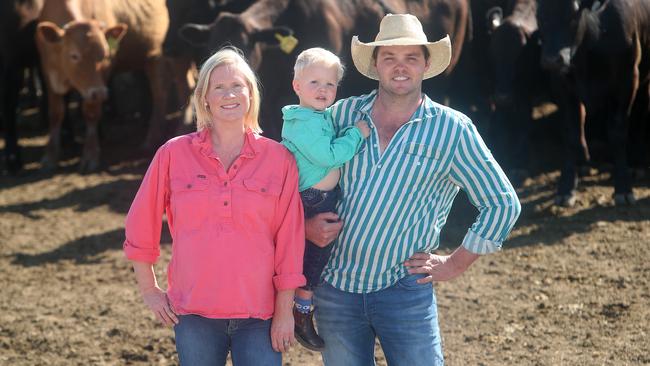

Managing a burgeoning agribusiness empire, albeit until recently with his grandfather by his side, undoubtedly causes some level of pressure. But James’s wife Fiona says he has an innate ability to deal with it.

“James has grown with the business and he’s never been out of his comfort zone – the growth of the business has just seemed very natural the whole way through,” Fiona says. “He wears stress well.”

Forty-one per cent of JHW Paterson’s revenue is derived from the sales of first-cross Wagyu cattle compared to 28 per cent from cotton, 11 per cent from custom feedingothers’ cattle, and 8 per cent from the sale of British-bred cattle.

From an asset perspective, the Patersons’ Victorian properties account for 33 per cent of the business’ value, followed by the NSW properties (30 per cent), a water portfolio (26 per cent) and livestock (11 per cent).

That James is totally across the numbers is no surprise to those who know him. Fiscal responsibility was drummed into him at a young age, according to Cramer, who was the family business’s accountant for more than 40 years.

“Gordon would go to meetings with the banks and he would have James by his side, and it was almost like he wanted to challenge those bankers to refuse to talk with James,” Cramer says.

“I wasn’t privy to those bank meetings, of course, but Gordon would speak with pride about how James handled it, and how he would let James close the deals.”

His negotiation skills were put to the test in a high-profile sense in 2019 when the Patersons placed one of their biggest feedlot customers, the Chinese-backed Harmony Operations, into receivership over unpaid bills of more than $11 million.

Under the arrangement, the Patersons bred cattle for Harmony, fed them at Hells Gate, and then sold them back to Harmony to supply premium brands.

That the deal went sour is well known. Perhaps less so, is that 20 months later, Harmony Operations was back trading unconstrained and, to this date, remains as Patersons’ largest customer.

In his mid-20s, James was alongside Gordon as they untangled the mess, and James acknowledges that there would be some who could not understand why they would continue to work with Harmony.

“I think what it shows is that we always treated these business dealings with respect, we kept the relationship healthy and we moved on,” James says.

RARE QUALITIES

Cramer describes James as a unique individual, with an innate sense of fairness and respect.

That was on show, Cramer says, when he had his first real contact with James at his father Lachlan’s funeral when James was just 16.

When mourners exited the church, James and his sister, Olivia, stood beside Gordon and wife Verna, and shook everyone’s hand.

“It was remarkable – I was blown away that someone that age could do that,” Cramer says. “James is so respectful and always has been – he was brought up to respect people and that never changed as he grew older and took more and more control of the business.”

Cramer is full of praise for James and the way he’s stepped up, and uses the word “enigma” as he watched and supported the young man as he became the boss.

“It was clearly hard on James losing his father, but it was also hard on Gordon, who had thought in his early 70s that he was going to step back from the business,” he says.

“For about five years, the business was in limbo but then they regrouped, and they were off. It was like Gordon got another lease on life, and it’s amusing to think about how Gordon would have been in his 80s going to the bank and have that steely look in his eye as if to say ‘Don’t even think about my age’.”

CALCULATED RISKS

Cramer has witnessed first-hand the growth of JHW Paterson and Son and says the bold moves are always calculated.

“There is risk and there is calculated risk, and these expansions and decisions were calculated risks,” he says.

Cramer thinks he’s pinpointed some of what’s driving James to continue to expand. “He clearly loves what he does,” he says. “There’s no sense of ‘I’m the boss, I run a big business’ at all, more an unbridled enthusiasm to continue to take on projects and take opportunities.

“You would have to love it – growing up at Hells Gate with the 45C heat and the flies and the smell of the feedlot, working so hard, you would need to love it to want to be in it.”

While James’s biggest mentor was his grandfather, others such as Cramer have been integral in supporting him to take on and grow the JHW Paterson and Son business.

Hells Gate manager Wayne Johnson has been a steady presence with his knowledge and agricultural smarts, as have other long-term employees.

James is a big believer in working alongside his staff and scoffs at being office bound, despite the massive amount of planning that’s needed in an operation of this size.

That’s not to say he won’t do the office work – training in agribusiness at Marcus Oldham College at Geelong and the support of experts means he knows his way round more than just a profit-and-loss statement, and quarterly meetings ensure the business knows its numbers.

But he’s also happy helping prepare machinery and equipment to plant crops, explaining the workings to what he calls, ironically, junior staff, despite himself being still considered young in most agribusiness circles. James says staff management is part of the business he loves with more than 60 permanent workers on the books.

“We are proud that we have long-term staff, managers that have been with us for years,” he says. “Yes, we may have moved to a more corporate operation when it comes to scale and business structure, but we want to maintain the feel of a family business.”

‘ENVIRONMENT WHERE IDEAS ARE ENCOURAGED’

James says the feeling of belonging, of autonomy and respect, means he wants anyone on the team to come to him with ideas.

“You want an environment where ideas are encouraged, not shot down, and there are no real recriminations,” he says.

“If a manager has an idea, we back it and if it doesn’t work out, then we don’t need to tell them that as they will have worked it out themselves.”

At their home base at Pevensey Station, part of the Kooba aggregation, Fiona, a solicitor who is now a director of JHW Paterson and Son, and James say they have no master plan nor set goals for the business. What they are prepared for is to take up any opportunity that they feel will honour and grow the legacy of the Paterson family in agriculture.

Over the past few years, Gordon had, step-by-slow-step, given more responsibility to James, and in the final eight months of his life, imparted pearls of wisdom as he signed off on his agricultural journey.

“He was still alert, despite being in a wheelchair, and was still so switched on and I continued to seek his advice on so many things,” James says.

Fiona says the relationship between her husband and Gordon was special. “It was beautiful to watch – Gordon never told James anything, more that he guided him,” she says. “In his final year, Gordon was very comfortable about the business and its future.”

With the next generation of Patersons coming through – Will is 2½ and a new baby on the way – James remains as passionate and enthusiastic about farming, which is a sweet mix of youthful exuberance and savviness rolled into one.

Originally published as Meet the 32-year-old running a multimillion-dollar farming empire