Centenarian neighbours show how a life well-lived works for them

They met at primary school in 1929, have been neighbours for more than 70 years and now these western suburbs centenarians are sharing the secrets of their long and wonderful life.

Victoria

Don't miss out on the headlines from Victoria. Followed categories will be added to My News.

They would have to be Australia’s oldest mates, certainly up there as the longest living next-door neighbours. Wal Hopkins and Vern Roberts first met at Geelong Road Primary School in Footscray in 1929. You read that right: These two western suburbs legends have known each other for more than 90 years and have lived next door to each other for 74 of them.

They live in almost identical neat, white weatherboards with a shared wooden fence that they lean across each morning to check on not only the news of the day in their shared copy of the Herald Sun, but also each other.

That connection – along with their love of family and friends and of a lifetime of being active in their community – is, say experts, why these two have lived 100 years.

IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE

Hopkins is the older of the pair, having turned 100 in May, and Roberts will match his mate in October.

He is already busy planning the party. About 120 people turned up for Hopkins’ shindig, where he shared stories of his wonderful life.

The list of his achievements is long – recognition of a life well lived.

Hopkins was awarded an Order of Australia; he holds Scouting’s highest award; is a life member of the Footscray YMCA; a life governor of Footscray Hospital; and is a long-time supporter of many local sporting clubs, including the Footscray Hockey Club.

In 2004 he was nominated for Australian of the Year, but Hopkins says his contribution to community affairs was insignificant compared with the successful candidate.

That humility is typical of the man who needs to be nudged to reveal he was elevated to “Legend” status with Hall of Fame recognition for his decades of service as a VFL umpire and adviser in the Footscray District League.

“He was always determined to make 100,” says daughter Julie Hopkins.

Wal Hopkins says you only get out of life what you are prepared to put into it, and the key is to be respectful and kind. It is an edict both Hopkins and Roberts live by. “Treating people the same as you would like to be treated helps you make life more enjoyable,” Hopkins says.

Roberts says there are two things that are important in life: “Be caring towards one’s parents and the second is have respect for other people.”

Each day the two meet at their shared fence to swap a few laughs and the Herald Sun.

Lifelong readers of the newspaper, Roberts says they have a daily custom of placing the newspaper inside a piece of PVC pipe so that when one has finished reading it, the other can have a turn.

After primary school, they lost contact until by coincidence they bought neighbouring blocks of land in the western suburbs. By then they had married their sweethearts, Evelyn Hopkins and Gwen Roberts, who would become the best of friends. Their wives died a year apart, almost to the day, both aged 93.

And while it would be easy to fill these pages with the achievements of Roberts and Hopkins, first the question that must be answered: How did they make it not only to 100 years but in such good shape, physically and mentally?

They offer that they have never smoked, are moderate drinkers and have always been active – physically, socially and within their community.

Nor has there has ever been a cross word between the pair.

“We also did all our own home maintenance and we live still independently,” Roberts says. “And we never had takeaway meals.”

They have also enjoyed a lifetime of good health, although Hopkins admits to a bit of trouble these days with his eyesight.

As for Roberts, he says his hearing it not what it used to be.

BRAIN HEALTH

Researchers say the lifestyle of Roberts and Hopkins explains not only their longevity, but the quality of their long years. And they say it is not out of the reach for many of us.

Monash University Professor Keith Hill from the School of Primary and Allied Health Care is the inaugural Director of the Monash Rehabilitation, Ageing and Independent Living (RAIL) Research Centre.

“It doesn’t matter where you sit on the health spectrum, well or frail – you can still improve,” he says. “It is never too late to start.

“We all get very busy in our young and middle life and often don’t start to think about lifestyle factors until we get to our 50s and older.

“The basic things are eating well and keeping fit, which means being physically active, and there are many different ways you can do that; it doesn’t only mean going to the gym.”

With a background in physiotherapy, Hill has studied exercise across older age groups and says it can help achieve improved health outcomes, including reducing the risk of a range of chronic health problems, such as diabetes and some cancers. “Exercise also helps increase life length and quality,” he says. “Often we see older people portrayed as frail and in poor health, but it doesn’t have to be that way; there are some very well older people in our communities.”

Hill warns one of the biggest risks for ageing Australians is a fall. “A third of people over 65 fall every year,” he says. “Many are not serious falls, but people lose confidence even from a minor fall and start to do less physical activity.”

Hill says balance training that challenges the brain can help reduce the risk of falls.

“Medications can also contribute to the risk of falling, so having medication reviews is important, as well as reducing falls hazards in the home or reporting outdoor environmental hazards, such as an uneven footpath that needs repairing.”

So, does Hill want to live to 100?

“I am not sure 100 is the magic age, but I want to be able to live as long as I can with a reasonable quality of life.”

He plans to spend more time with family, including his three-year-old grandson, Clancy, and has now reduced his work hours for a better life balance. “Keeping mentally active is critical; it is another part of the jigsaw that is important, particularly as you transition out of the workforce,” Hill says.

LOOK ON THE BRIGHT SIDE

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare reports Australians are living longer.

While we may not yet be home to a prized “blue zone” – a phrase coined by explorer and author Dan Buettner to describe those unique regions where people live longer and better – babies born in Australia in 2024 are predicted to live well beyond their 80s.

Monash University Professor Velandai Srikanth says if you look at people who live to be 100 and beyond, they have behaviours and characteristics that helped them reach that age.

The director of the National Centre for Healthy Ageing says most centenarians and those who have made that rarefied group known as supercentenarian (living 110 years or more) have in common a positive outlook on life.

“They tend to have a tight and well-organised social fabric, which means social connectedness and being a productive part of community, and purpose is often found in such people,” Srikanth says. “They also have the ability to cope with stressors and challenges that life throws at them better than average.”

His research also reveals many centenarians have grown up with exercise being a part of life, have maintained it through their middle years and kept it going in later life.

“We found, for example, what children do when they’re young – how fit they are, how active they are – predicts how well their brain health might be at midlife,” Srikanth said.

He believes this may also be key to keeping brains more resilient and even to protect against diseases such as dementia.

“One of the key protective factors that we look at is how resilient the brain is against injury, how much reserve it’s got to withstand the kind of injuries that happen over time,” Srikanth says.

“And so people who are relatively healthy, who eat well, exercise well and have these social connections, have purpose, do all the right things that we know of, they probably tend to have better brain reserve through their mid-to-later lives.”

WHY WOMEN LIVE LONGER

Srikanth says women who live to 100 and beyond probably have something about them that sets them apart from men in how their hormones have protected them, and how the immune system is set up to help women age better.

“They usually have healthier habits than the average male who reaches that kind of age,” he says. “They also tend to seek healthcare more. This not only helps them live longer, but means they have better brain health.”

Advances in public health and screening for breast and gynaecological cancers have also had an impact on women’s health, Srikanth says.

It also means women can work longer, but experts say there need to be changes to work environments so that can happen.

First and foremost, research has found, women want to be appreciated more.

A world-first study led by Monash University professor Karen Walker-Bone investigated the global phenomenon looking at why women leave the workforce after 50.

Her study looked at more than 4400 women in the UK, but she says the results were mirrored by Australian women.

Walker-Bone says, in Australia, as in the UK, there is an increasing number of women in the workforce due to issues like changes in the eligibility age for the pension from 60 to 67. She says this particularly impacted women born after March 1950.

“Globally we are seeing an expansion in older women working since the 2008 global financial crisis, and it is likely that increasing numbers of women return to work in their 40s to 60s for financial reasons,” she says.

Walker-Bone found there were simple ways to retain an older female workforce after looking at what jobs older contemporary women do, when they leave their jobs and what factors predict it.

The results were published in the Occupational Medicine journal. Her study found leg pain and poor self-rated health were some of the reasons behind women leaving the workforce, but those who felt they were appreciated, felt secure in their jobs and were satisfied in the role likely worked for longer.

CONNECTION CRUCIAL

More Australians than ever before are reaching the age of 100 and beyond. The latest census data records 5547 Australians 100 years or older and reveals life expectancy has also increased by 13.7 years for males and 11.2 years for females since the 1960s.

But there is living to a ripe old age, and there is living a quality life.

Hill talks not only about increasing life length, but what’s needed to achieve a quality of life.

That, he says, is about keeping the mind active and doing simple things like watching quiz shows on TV or doing the daily crosswords or puzzles.

“The other one is being socially connected,” he says, adding that this social connection can be achieved online.

“I would argue there is a fair difference between online connections versus face-to-face, but nonetheless both can be valuable in terms of general mental health and wellbeing,” Hill says.

Australia’s oldest living male and female both came from families of centenarians and there is something to be said for country living, as they were from regional towns.

Christina Cock lived to 114 years and 148 days and her daughter Lesley died at the age of 103 years and 200 days.

Our oldest living male, Dexter Kruger, was 111 years and 188 days old when he died three years ago. It was reported at the time that two of his cousins lived to 100 and he had an aunt who reached 103.

BRIGHT LIGHTS

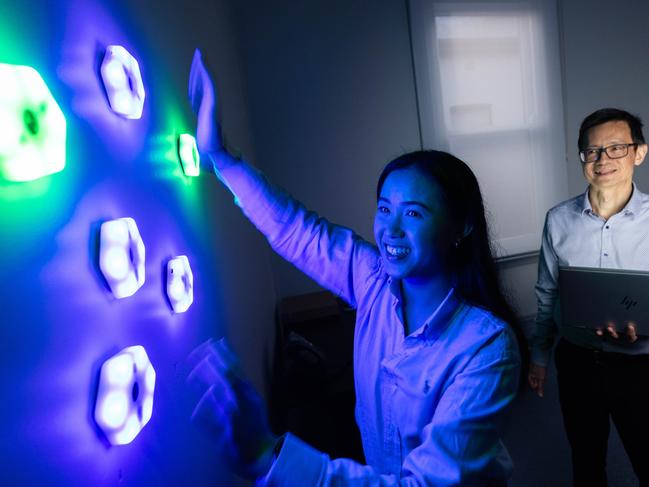

Melbourne physiotherapist Cindy Phan is working with geriatrician Kwang Lim to develop a unique program that trains the brain and body at the same time.

Professor Lim is the clinical director for aged care at the Royal Melbourne Hospital and Phan has a special interest in working with older patients to help them keep physically fit.

She says their Bryta program came about because Lim would make recommendations to patients about how to improve their physical and brain health, but there were no physiotherapy-led programs to which he could send them.

Together they created Bryta using “reaction” lights that are programmed to use different parts of the brain and body, to get older people not only up and moving but cognitively active.

“We’ve got memory activities programmed and, because they’re lights, we can position them so that people are reaching, they’re using their legs, they’re standing from a chair and running up to the wall,” Phan says.

She says said most are aged from 65 but the oldest participant is 95.

“I don’t think it is ever too late for people to join,” Phan says.

INTO THE FUTURE

“The most important thing that we can do as physicians and researchers is to enhance public health messaging for the lifespan,” Srikanth says. “So from a young age, even during pregnancy, going through midlife, making people aware of the fact that the better your attitudes towards public health, diet and exercise, the more likely you are that you’ll live longer and be healthy when you live

longer, right?

“The trouble with public health messaging is it reaches some, it doesn’t reach everyone, and then there are societal issues that prevent it from being completely successful.

“For example, there are socio-economic disparities that prevent people from being able to be healthy or access healthy lifestyles, such as when the cost of foods become difficult.”

Srikanth says this is where reform is needed, to improve equity of health for people.

“I think there’s going to need to be workforce opportunities and productivity opportunities for people living beyond their midlife and 60s and 70s, to create purpose for them,” he says.

“We are also going to need a workforce (to care for them) as the population ages.

“We will also need the wisdom of older people being transferred to younger people, encouraging them to engage purposefully. So that’s on us as a society and governments to enable that.”

While it is a significant undertaking,

Srikanth says it is fantastic to think that if we do these things right, we can live to a 100 and beyond well.

MATES FOR A LONG LIFE

At 99 years old, former RAAF flight rigger Roberts still stands straight and has an impressive memory for detail.

He has written extensively about his time on a Liberator aeroplane during World War II. Roberts was in a B-24 Liberator Squadron and is likely the oldest surviving witness of the end of World War 11.

He was there at Morotai, a rugged island in Indonesia, when General Sir Thomas Blamey and the Japanese generals came together to sign the formal surrender of the Japanese army on September 9, 1945.

Roberts marched in the Anzac Day parade to the Shrine of Remembrance until he was 94. Now he is helping to restore a B-24 Liberator – the only one in Australia – a beast dormant in a hangar in Werribee that Roberts and other volunteers started in 1995.

“We were home for Christmas 1945. And then it was time to pick up civilian life where we had left off,” he says.

And that included catching up with neighbour “Wally” – something the pair has been doing ever since.

More Coverage

Originally published as Centenarian neighbours show how a life well-lived works for them