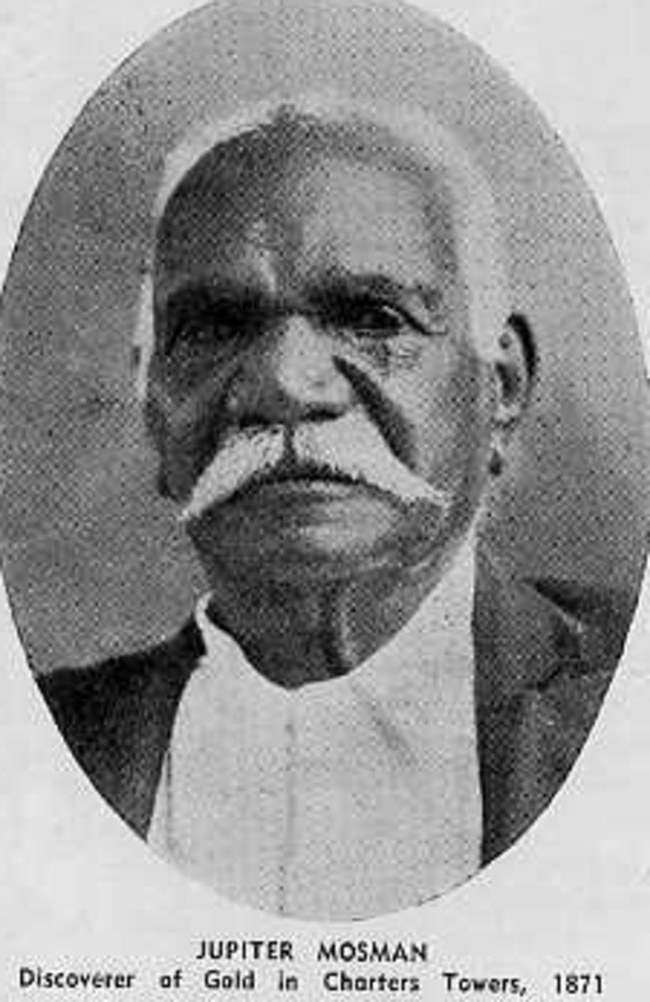

‘We’re surviving on rental income’: Jupiter Mosman Housing Company marks 50 years

In 1975 a group of homeless Aboriginals got together to buy property – 50 years on, and their not-for-profit has grown to be one of the biggest ratepayers in Charters Towers.

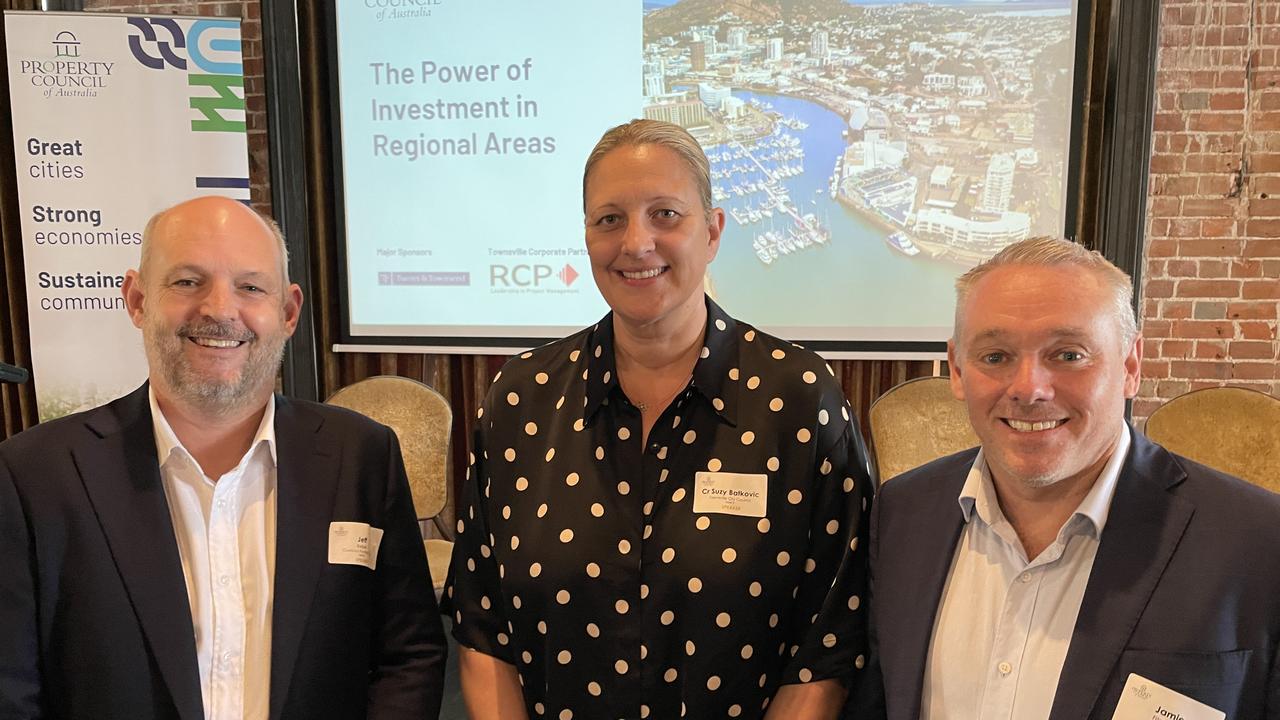

Townsville

Don't miss out on the headlines from Townsville. Followed categories will be added to My News.

In 1975 a group of Aboriginal people living in a boarding home and under bushes on the outskirts of town got together to collectively purchase seven houses.

Fifty years on, and the Jupiter Mosman Housing Company (JMHC) has grown to be one of the biggest ratepayers in Charters Towers managing 39 homes.

JMHC chairperson Tania Ault remembers being a small child sitting at the feet of adults as they discussed ways to house themselves.

“I was probably sitting on the floor playing around, I didn’t have any idea how serious it was,” Ms Ault said.

Despite reaching its 50th anniversary on April 4, JMHC is fighting harder than ever to provide housing after its Federal funding was cut off in 2006 with the closure of ATSIC (the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission).

Since then its properties have been running off rental income alone.

The post-Covid housing crisis, rates, insurance hikes and the increased cost for tradies to maintain their ageing houses has also placed a huge amount of pressure on the service, but its current leaders are standing strong and making plans.

Leaving the cattle stations

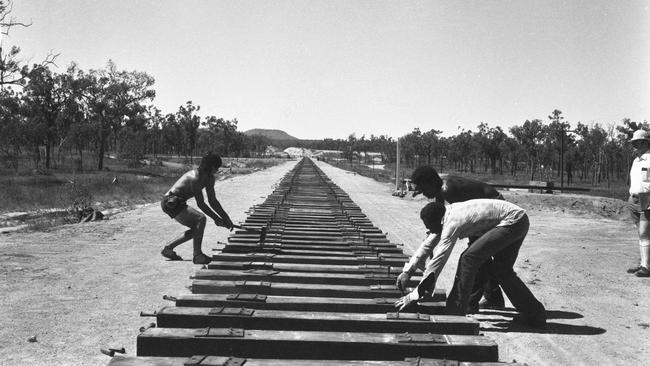

Before the ‘67 referendum, most of Charters Towers’ Aboriginal population (Gudjala people) were working on cattle stations under the Aboriginals Preservation and Protection Act.

“They were working under the Act, and they were only allowed off the stations for three days a year around Christmas,” Ms Ault said.

“If they didn’t return in three days, the police would arrest them and send them to Palm Island. We called it Punishment Island then.”

When the ‘67 referendum was passed under Prime Minister Harold Holt, the Australian Constitution was amended to include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders as “the people” and gave them equal citizenship.

“When the referendum happened our elders were ousted off the stations, but there was nowhere to live in town either,” Ms Ault said.

“Aboriginal people were effectively set free, and by the time they came back to their towns they had no means to survive and nowhere to live.”

Meetings at The Phoenix

Ms Ault said she remembered meetings happening at The Phoenix, one of the only boarding houses in Charters Towers that accepted Aboriginal tenants.

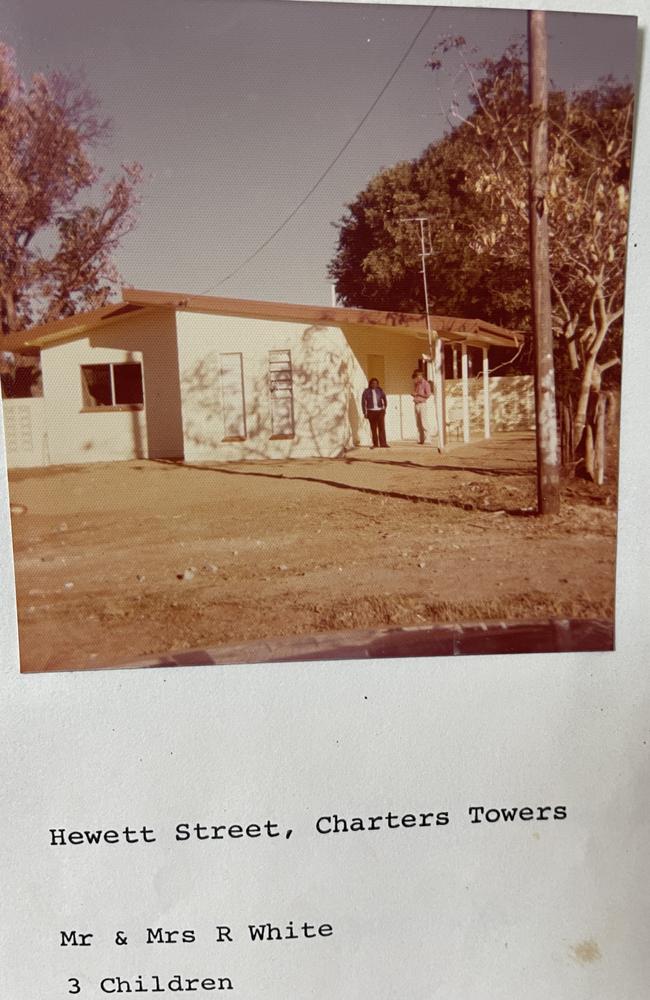

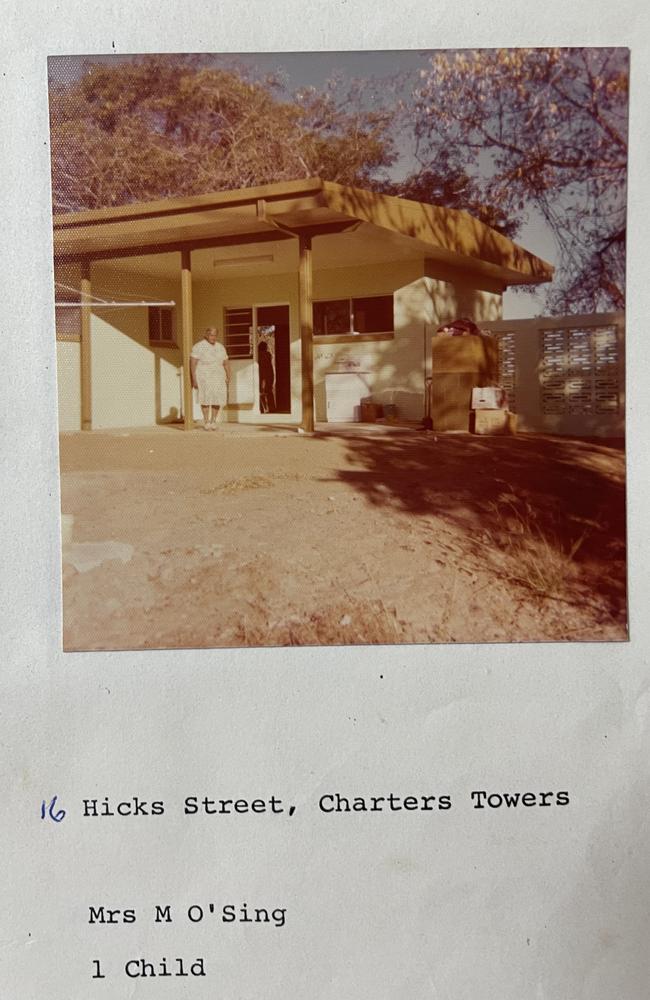

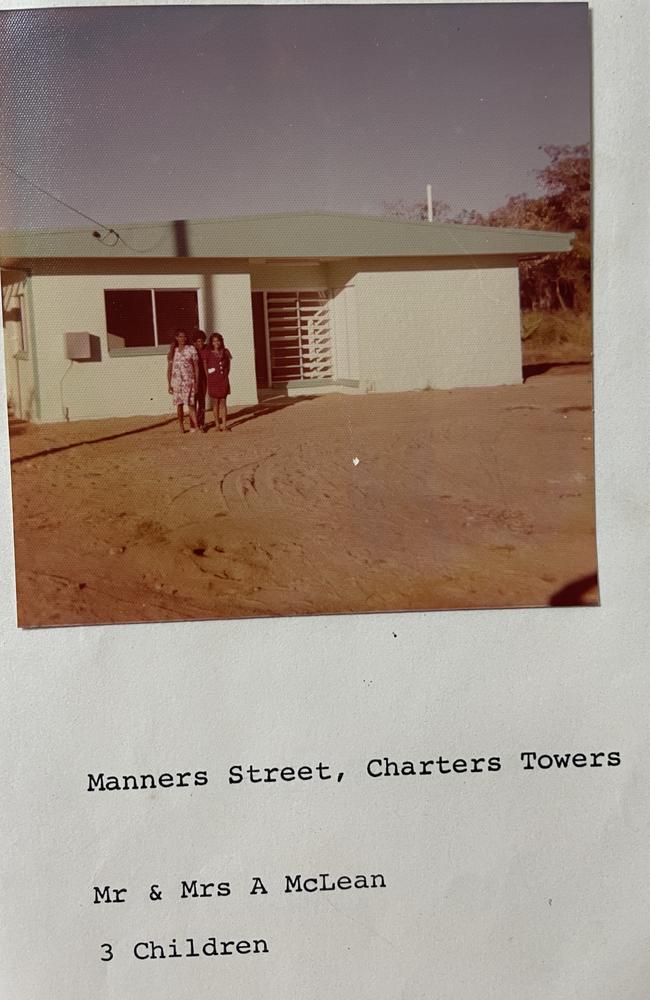

“They were having conversations in October 1973 and in 1975 they became incorporated and were provided $419,000 by the Federal Government to purchase eight houses and build three more,” Ms Ault said.

The first seven homes

JMHC homelessness service co-ordinator Jennifer Huxley remembers living in the scrub outside Charters Towers as a child.

“At the time there were families living in the scrub, called fringe dwellers, having a terrible time because occupation for them wasn’t allowed,” Ms Huxley said.

“The elders had to prove there was a need for housing in Charters Towers. I remember the Federal Government sent people down to take pictures of my family living under the trees in the bush, because they didn’t believe people were actually living in those conditions.”

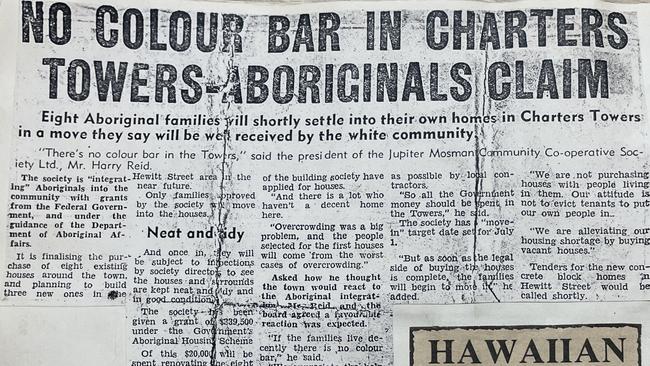

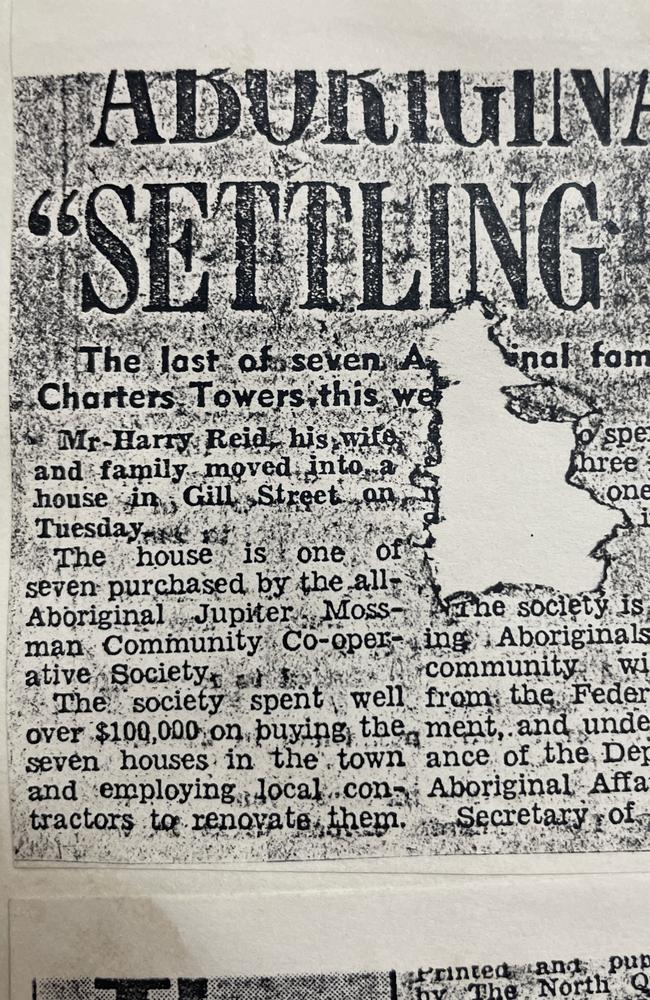

Ms Ault said while JMHC were getting those first families into the homes, they were “copping a lot of flack” from Charters Towers residents.

“People were not happy, they were writing into the newspaper and it’s all there to read,” she said.

“They wrote to the newspaper on the 26th of January in 1976 of their dissatisfaction of Aborigines living in these homes.”

Surviving on rental income alone

Keeping the Jupiter Mosman Housing Company going was never going to be easy – to date, the not-for-profit has entered administration twice.

“We’re running solely on our rental income,” Ms Huxley said

“And we’re also one of the biggest rate payers in Charters Towers.”

Ms Ault agreed, saying the housing crisis was stretching all budgets to the brink.

“Rates, insurance, repairs and maintenance, operational costs get paid out of the rental income,” she said.

Ms Ault said since 2023 the not-for-profit has been under pressure.

“It’s hard work. It’s heavy. Especially in a housing crisis,” she said.

“We previously had a CEO who was here for 22 years and I had to actually make a decision. I stood on my own for a bit, we had to go into caretaker mode.

“I’m glad I didn’t walk away, because if I had, those doors would be closed, and what a shame that would be,” Ms Ault said,

“I made an oath to myself I wouldn’t allow that to happen. So myself and the other board of directors had to have a lot of honest and frank discussions.”

Dreams of building units, new homes

For Ms Ault the many hours she puts into JMHC are deeply personal – she lives in one of the 39 JMHC homes, which is how she ended up on the company’s board, and what prompted her to step up and become the chairperson in 2021.

“At one stage there I honestly thought we were going to have to close our doors, which meant 39 families were going to be out on the street, including myself,” she said.

Ms Ault said she now feels the board and employees have gotten through the rough seas and have stabilised JMHC.

“We’re a lot more educated about how to function as a company. We’ve got well educated people who know their way around government and how government works,” Ms Ault said.

“We’ve got clear goals, a 10 year plan.”

Today, their dream is to add more homes to Charters Towers – particularly modern, sustainable and easy to maintain units.

They’ve been keeping a close eye on the Federal and Queensland Government’s talking points and new policies, and travelling to Brisbane to talk with bureaucrats, but despite being perfectly placed to help with Closing The Gap targets and Breaking the Cycle action plans, they’re finding it hard to get any attention.

“You would think with the amount of money that goes into developing these plans and establishing peak bodies to advocate on our behalf that would be the opening door but the door still remains closed,” Ms Huxley said.

“They talk about self-determination. You’ve got 50 years of self-determination sitting here right in front of your face.”

Ms Huxley said it wasn’t just them being overlooked.

“If you look at other ICHOs (Indigenous Community Housing Organisations) it’s the same thing, look at Yumba in Hughenden and other housing organisations in the west,” Ms Huxley said.

“2006 left services and people in need with no alternative but to swim or sink … They forgot they had us still here on the ground.”

Ms Huxley said the goal for JMHC is to keep their autonomy at all times and grow.

“Because that’s what the legacy is, but we also want to provide more sustainable and suitable houses,” Ms Huxley said.

“A lot of our older houses are on big blocks. If a bucket of money falls from the sky, we could demolish those houses and build a duplex or unit complex … but what’s it cost to build a house these days? It’s over a million dollars for a small three-bedroom house.”

The homelessness service

One big factor helping JMHC continue in Charters Towers is their specialist homelessness service, which is fully funded by the Queensland Government and funds five JMHC homelessness service staff.

This service has been running at 100 per cent capacity year in, year out, since it started in 1984, according to the JMHC.

In recent years the homeless service has grown, and the Jupiter Mosman team now lease Department of Housing properties and uses them to temporarily house homeless people in Charters Towers.

These properties include a four-bed men’s shelter, and five residential homes.

“These are all families, and very responsible families, but it comes back to housing affordability and the housing crisis,” Ms Huxley – who’s the homelessness service co-ordinator – said.

“We have a really good relationship with the Department of Housing. You couldn’t ask for a better department, because they bloody try.”

Ms Ault agreed.

“We deal with a lot of departments and they are probably the most helpful and capable of all the ones we’ve dealt with,” she said of the Department of Housing.

“Between Jupiter and the Department of Housing, it’s a really good partnership.”

Why did the funding stop?

JMHC’s initial funding came from the Federal Department of Aboriginal Affairs, which was abolished in 1990 and amalgamated into the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC)

The ATSIC was abolished in 2005.

Currently the federal department overseeing Aboriginal programs is the NIAA (National Indigenous Australian Agency).

It is understood the Federal Government moved away from funding ICHOs (Indigenous Community Housing Organisations) directly in 2009 and any remaining funds for remote Indigenous housing were provided to the states by the Commonwealth through the National Partnership on Remote Indigenous Housing Agreement.

Part of this funding was made available to ICHOs, but the terms of how funding was allocated were decided by the state government.

Essentially – the funding got shuffled around and hidden away.

Federal Member for Kennedy Bob Katter was contacted for comment – his staff said they had reached out to JMHC.

Liberal candidate for Kennedy Annette Swaine was contacted for comment, she did not respond.

The NIAA was contacted for comment, they did not wish to speak on the record.

More Coverage

Originally published as ‘We’re surviving on rental income’: Jupiter Mosman Housing Company marks 50 years