Tasmanian Elders Council faced a disasterous future

Headquartered in St John St in Launceston, the Elders Council is a place where traditions and practices are handed down and stories, history and culture are shared. But its future is under threat.

The Launceston News

Don't miss out on the headlines from The Launceston News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A KEY cultural link in Tasmania’s Aboriginal community could be forced to close its doors by Christmas if urgently needed funding is not secured soon.

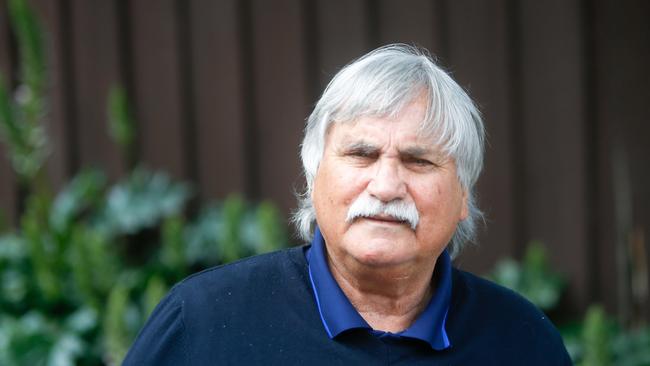

Aboriginal Elders Council chair Clyde Mansell says losing the organisation after more than 30 years of operation would be “disastrous”.

Headquartered in St John St in Launceston, the Elders Council is a place where traditions and practices are handed down and stories, history and culture are shared.

It is a place of community, support and where both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people can find solace without judgment.

The elders there support cultural and community initiatives such as the four-day wukalina walk at Bay of Fires, providing support for police dealing with troubled youths and simply feeding those in need, sometimes with cash from their own pockets.

“The Elders is all about cultural continuance and ensuring that cultural relationships are in keeping with the way the community has evolved over the years,” Mr Mansell said.

“They play that vital role of ensuring that cultural story is maintained and that young people have a place to come and seek support if they need help.”

The collective wisdom within Chalmers Hall – the home of the Elders Council – has helped many find their identity, perspective and family.

A young woman who visited the elders recently with drug and other issues “straightened herself out and got her life back on track” with their help.

“The last I heard, she was considering taking on a guiding course to go on the wukalina walk,” Mr Mansell said.

“After spending time with some of the elders, she understood her place in the community and was better suited to leading a worthwhile existence.”

Sharon Holbrook, who was taken from her mother in Launceston as a child to an orphanage in Victoria, did not know she was Aboriginal or Tasmanian until she was 59 years old.

Through the elders network she was able to learn about her parents who had since died, connect with other family members and after being told she was an illegal immigrant her whole life, finally felt whole.

The Elders Council recently received a $30,000 state government grant to help keep the Administration operating after applying for $109,200, but that will only last until December.

The organisation will close then unless additional funding is sourced.

The Elders Council runs two specific community programs.

One employs a co-ordinator to help elders retain their independence at home through the Commonwealth Home Support Program (CHSP).

The other – for which funding expires next year – sees the elders support people battling family violence related issues.

“Each of those programs gives a small percentage of their funding for administration, but it’s not enough to keep [the Council] going,” Mr Mansell said.

Costs including an administrator’s salary, insurance, phone bills, power and building maintenance still need to be covered.

“[The Commonwealth government has] said to us recently that they don’t fund the administration of organisations.

“But … an organisation like the Elders [doesn’t have] programs that give them income like other organisations.”

Mr Mansell said forming the delivery of the Elder’s work into approved programs to gain Commonwealth support had failed repeatedly over the past five years.

The Council has engaged a business consultant to help find other revenue streams.

Finding a corporate sponsor is one hopeful option.

“We are losing Elders too fast before we can [record] their stories, which is what we could get into if we’ve got the ability to access funding – maintaining storylines for community people,” Mr Mansell said.

“My mother was a founding chair of this organisation. I don’t want to be the chair when they close the doors.”

Mr Mansell said losing the elders, “a key link to cultural continuance”, would be “disastrous”.

SHARON RETURNS TO COUNTRY

A SHUDDER ran through Sharon Holbrook as she planted her foot on Tasmanian soil seven years ago knowing she was finally “back on country” after 54 years away.

She had finally received her birth certificate which revealed she was born in Launceston to an Aboriginal mother.

Until then she had “hated” her mum, believing she gave her up to the notorious Ballarat Orphanage, which closed in 1968 and was later demolished.

The unfolding truth was that she was ‘stolen’ by a racist institution unable to accept her family arrangement.

Mrs Holbrook, now 66, was born to an Aboriginal mother and white father and was one of 15 siblings.

Although many of her siblings weren’t born by the time Mrs Holbrook was separated from her family, they were “all taken eventually”.

At five years old, Mrs Holbrook found herself in “skimpy clothes” in the cold scrubbing floors with a toothbrush and subject to neglect and abuse as many of the stolen generation were at the Ballarat Orphanage.

“I have some awful memories from there,” she said.

“I never got to see mum or dad again and it’s very hard.”

After 18 months Mrs Holbrook was adopted by a white family from Preston, Victoria and was loved and cared for.

The family had two other adopted daughters.

One was later revealed to be Mrs Holbrook’s biological sister, Roseanne.

In the decades following, Mrs Holbrook was told by government departments that she had no birth certificate, that she was an illegal immigrant and that she was not Australian.

Milestones like marriage and overseas travel were complicated and tarnished by painful reminders from the Commonwealth that legally, she was “a nobody”.

“Without a birth certificate, it’s very hard. You’re not complete.

“I applied for a passport to go away overseas and was called an illegal immigrant. It hurt.”

In 2013, a letter containing Mrs Holbrook’s birth certificate arrived at her home, thanks to the Bringing Them Home program.

“When I found out I was Aboriginal, God it was a shock.

“Bringing Them Home sent Roseanne and I over here [to Tasmania] a couple of times.”

The first time Mrs Holbrook stepped off the plane in Tasmania, a shudder through her body let her know she was “back on country”.

She was welcomed by the elders at the Aboriginal Elders Council of Tasmania in Chalmers Hall in Launceston who knew who she was.

They had known her mother who was born on Cape Barren Island and died in 1974 at the age of 47.

They told her stories and reconnected her with her siblings.

“I think my mother died of broken heart,” Mrs Holbrook said.

Her father, a police officer in Launceston and then a harbour master at St Helens, lived 87 years and died just over a decade before his daughter found her way home.

Mrs Holbrook settled in Launceston.

“Apart from missing out on a lot of culture, it’s like I never left,” she said.

Her uncle Murray took her “out on country” two years ago, painted her with ochre and conducted a smoking ceremony.

“He made me a fire stick to welcome me back to country and that was the most emotional thing.

“Afterwards I just got a fold up chair – it was down where the last lot of Aborigines were taken off and out to the islands – and I just sat there looking at the water.

“The ocean was just so peaceful.”

Mrs Holbrook, a mother of three, grandmother of nine and great grandmother of three, now ensures her descendants are in touch with and proud of their heritage.

At the Elders Council she cooks for the wukalina cultural walk, does welcome to country ceremonies, assists police dealing with troubled youths and feeds and supports those in need.

“I’m very proud to be Tasmanian Aboriginal,” she said.

“I know where I belong. I know where I come from.”