Catching a thylacine by the tale after decades of waging war of the Tasmanian tiger

Can magical fantasy secure a rare win against calculated odds and the cold mechanics of science and reason, asks SIMON BEVILACQUA.

Tasmania

Don't miss out on the headlines from Tasmania. Followed categories will be added to My News.

MY heart leapt when I read this week about a thylacine pup caught on film in the bush — but it sank when I saw the image was nothing like a tiger.

While I strongly suspect the famous carnivorous marsupial is extinct, I hold a childish hope to be proven wrong — magical fantasy will secure a rare win against the calculated odds and the cold mechanics of science and reason.

MORE:

‘We found a thylacine’: Hunter claims discovery online

‘Proof’ Tasmanian tiger still exists

Tassie tiger find claim the ‘wildlife rediscovery of the century’

But let’s face it, the Van Diemen’s Land Company on the North-West paid scores of rewards for thylacines killed on its 140,000ha property from 1830 to 1900, and droves of colonial farmers spread across the island during this time, waging war on the tiger, believing it preyed on lambs.

Tiger pelts, treasured for their distinctive stripes, were sold to England in the 1880s to be fashioned into waistcoats.

In 1888, after decades of bloodshed had already been inflicted on the persecuted species, the Tasmanian government slapped a bounty on the head of an adult tiger worth a week’s wages.

Each year for roughly 10 years, between 100 and 140 bounties were claimed, until the kills began to slow and, without a single bounty paid in 1910, the scheme was scrapped. More than 2000 bounties were paid over 22 years of officially sanctioned slaughter.

And the killing did not end there. The tiger’s rarity and fame simply made it more exploitable. A pub at Whale’s Head on the West Coast, now known as Temma, advertised its “commodious hotel” as a place where “tourists in search of fun can be accommodated with kangaroo hunting, tiger shooting, fishing and yachting”.

By 1910, tiger skins were worth huge sums, and exporters paid small fortunes for live tigers for resale to London Zoo.

The last authenticated tiger kill was in 1930 by Wilf Batty who shot one snooping about his henhouse in Mawbanna, near Smithton. The last captive tiger died in Hobart zoo in 1936.

Reported sightings continue today, but not one has been authenticated in eight decades, during which there has been unprecedented disturbance of forests. The woodchip industry, with clearfelling, chainsaws, heavy machinery, high-intensity burns, plantations, regrowth, poisoning and roadworks, has been rapacious in the North, East and South for four decades.

Could a thylacine survive?

If there is hope for the tiger, I reckon it is in the wilds of the Arthur-Pieman Conservation Area and the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. It is intriguing to consider that during the bounty years, only 17 were for thylacines killed in this area, fewer than one a year and not 1 per cent of the total.

In contrast, about 700 bounties were claimed in the Central Highlands, with one Derwent Bridge resident paid for 53 tigers, all caught within 25km of his house.

This huge difference in claims is often explained by the fact tigers hunted in open grasslands fringed by forests where they have their dens. They were not too active deep in rainforests. They were more prevalent in the state’s grassy, marshy highlands, midlands and coastal heath rather than the West’s mountain terrain.

But another reason for fewer bounties could have been the dearth of settlers. The rugged West resists urban sprawl, restricting larger groups attracted during mining booms to more localised towns rather than spreading out.

Could thylacines survive in the remote West, without being noticed? They certainly have been documented in the region.

Author Patsy Crawford wrote of dogs bringing down a tiger near Corinna, reportedly an Aboriginal name for a young tiger, in her recent book about legendary 19th century track cutter Tom Moore.

Moore wrote in his diary that his dogs, Spiro and Spero, “caught a tigre about 30 yards in front of me just after I started and had it killed before I got up to them. They eat everything but the skin which I took to make a cap of in remembrance of their first striped gentleman”.

Moore wrote a poem:

“Upon the turf there lay quite dead, A beast with stripes upon his coat

Young Spero bit about its head, While Spiro grasped it by the throat

So there a noble tigre died,

Just as the sun set golden rays

Shed light upon the mountain side. And victors of that savage fray.”

Not far from the fray, George Robinson, on a mission to round up and remove Aborigines to Bass Strait islands in the 1830s, wrote in his journal that “a bitch hyaena and a full grown pup run away before me … their tails stood erect … two other full grown cubs ran about scenting the ground. They performed several revolutions and loped over rocks and seemed in great agitation. They came close to where I stood but did not observe me. At last they got the scent of the old bitch and run off. It would appear that they were asleep when the bitch run away and on missing her when they woke commenced searching about.”

A year later, in the same area, Robinson reports killing a tiger and in 1834, near Sandy Cape, wrote: “… my dog Fly scented game and run to the bottom. I watched her and in an angle of some rocks with a sandy beach saw a large hyaena at bay with the dog. My son at the same time run down to the dog’s assistance and saw three young cubs who with the bitch had been feeding on the carcass of a kangaroo.

“The unexpected visitant surprised the animal, when she ran up the hill ... followed by the dog who from the commencement of the chase had kept close to the animal, occasionally biting its rump, when the hyaena would turn round and give chase to the dog and anon pursue its way, and at the same instant she turned the dog was biting her.”

After this almost play-like run, “Fly sprung and fastened its throat, and the two men killed it and brought it to me.”

Robinson kept the skin and his son captured a cub alive.

Later, they met some Aboriginal children who “seemed much amused at the live hyaena my son had brought in his knapsack as also the skin of the old one”.

Of course, Robinson’s tiger tales, almost 200 years old, offer little but the faintest hope.

The economics of the lash is a failure (February 27)

THE $25 weekly increase in unemployment benefits announced this week exposes the cruel nature of a heartless economic ideology that has enjoyed popular political support in Australia and much of the Western world for the past three or four decades.

This dog-eat-dog doctrine has again turned its back on widespread calls for a realistic increase in dole payments.

It reeks of a Darwinian “survival of the fittest” mentality and the aroma of essential oils, perspiration and fear that might be found in a 19th century bondage parlour.

This dogma, a particularly cruel strain of economic rationalism, is a major factor in political unrest sweeping Western democracies — because it enables the rich and powerful to become more so at the expense of the poor.

PM UNVEILS JOBSEEKER RISE OF $50 A FORTNIGHT

Hence, from the US to Britain, France and Germany, the downtrodden march in the streets, as formerly stable political states are shaken to the core by uprisings.

This dogma, which has dominated economic policy for decades, is creating a new poverty-stricken class that faces generational hardship and disadvantage, and is starved of the unprecedented spoils of wealthy democratic societies in the 21st century.

Democracy itself is being questioned by those being left behind in Western nations because decade after decade — no matter what party is in power: red or blue, Liberal or Labor, Democrat or Republican — a mean and spiteful economic strategy stubbornly holds sway.

As a result, there is growing anger from the subjugated and forgotten at the very notion of globalisation and liberalisation of economies when, in fact, it is not the expansion of market economics that is at fault but the failure of governments to ensure the spoils of its growth are equitably distributed.

Rather than look at growth as a chance to lift people from poverty, by providing those without work an adequate sum to survive, the Morrison government punishes the unemployed, deliberately making it harder than it has to be for them, and demands more from those on the dole, as a way of deterring others.

This sadistic streak, devoid of empathy, compassion or humanity, is to my mind the Western world’s most critical failing this century, and is a throwback to the punitive 19th century theories of crime and punishment that built a living hell at Port Arthur and dreamt up all manner of novel torture for incarcerated convicts.

Our nation is rich. Andrew Forrest is worth $23 billion and Gina Rinehart even more, about $28 billion. The average wage is about $80,000 a year. But over a million Australians — yes, about one in 10 in the workforce — will likely line up to receive the extra $25 in their payment when they lose the extra money they were granted in pandemic lockdown.

During the pandemic the unemployed demonstrated clearly that money in the pocket of the disadvantaged is immediately circulated on consumables — food, clothing, washing machines, fridges — and is an effective way to stimulate local economies.

Tasmania is a classic example of the effectiveness of this strategy — with a larger proportion of beneficiaries of JobSeeker and JobKeeper, the island was propelled to the head of the table of the states for economic growth.

Why can’t we get creative, accept there will always be a lazy few, and use the dole to stimulate local economies out of the pandemic? Why not use it to encourage people into training and education? Why not respect citizens and build inducements into our welfare system to encourage people to volunteer and to be skilful and daring with their job prospects?

But no, Employment Minister Michaelia Cash said the $25 weekly rise comes with obligations for the unemployed to apply for more jobs and, in a nice friendly, caring touch, enables employers to report recipients who turn down work.

Again, a strident puritanical strain of economic rationalism pits people against people, dividing the worthy from the unworthy and giving the former permission to walk all over the latter — lifters over leaners, battlers over bludgers.

It’s a pernicious ideology, whose followers have a taste for the sting of the lash.

The Reserve Bank, business groups and economists have been united in calling for a realistic lift in the dole, and responded in shock at the government’s mean response.

The Australian Council of Social Service chief executive Cassandra Goldie described it as a “devastating decision”.

“The last thing we need is for the government to turn its back on people at such a crucial stage,” she said.

Chris Richardson from Deloitte Access Economics said simply that the $25 was “not enough”.

TasCOSS chief executive Adrienne Picone said it would be a big blow to the 40,000 Tasmanians looking for work or more hours.

Australians have done a remarkable job through the many challenges of the pandemic.

A vast majority of us have heeded scientific advice, let our liberty be curtailed in the interests of the nation, and recognised the social contract we sign as a civilised people.

How about the government respond in kind and recognise this new maturity as a nation by treating the downtrodden with kindness and respect?

How about showing some empathy for families stuck in poverty and some acceptance they are not solely responsible for their dire straits, that luck and circumstance can conspire to seal our fates. How about we accept most people are good, given the chance?

How about moving into the 21st century, and dropping the puritan ethic by accepting most of us actually enjoy and identify with our work?

Australia is at a crossroads. We can see clearly where the path of our current trajectory leads. We have the chance to walk away from the failed 19th century discipline of the lash and to embrace a more caring style of market economics within a 21st century liberal democracy that aspires to lift people from poverty and refuses to leave anyone behind.

Life through the lens of an incredible snapper (February 22)

THIS column was to be about Facebook, news and the importance of journalism, but before I had written a word, I was delivered the sad news a dear friend of mine had died on Tuesday.

The news hit like a brick. I had only spoken to him in the days before Christmas and he sounded fine. He was on the Sunshine Coast, where he has lived in recent years, and was planning a trip to Tassie.

But, clearly, not anymore.

The realisation I’d never see him again stopped me in my tracks. Facebook, news, journalism and the column fell by the wayside as I was flooded with memories, hilarious memories of a dear friend, and our many, many adventures as wild as any swashbuckling pirate’s tale.

But, of course, all those yarns are doused by the godawful gut-wrenching hollowness that follows the realisation that memories are all that are left.

My friend is gone. I’ll never see his devilish grin or hear his infectious girly giggle ever again.

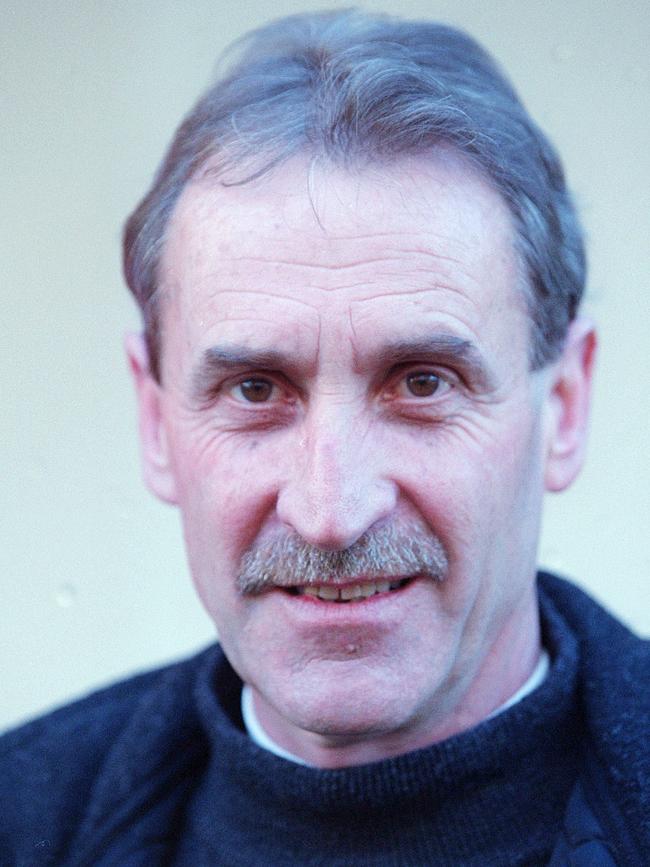

Drew Fitzgibbon was a photographer. A bloody good one.

I used to watch him stand under a pylon at SkyRace, just out of Launceston, alongside 20 professional cameramen from here, interstate and overseas.

The motor-drives would start firing, getting more manic the closer a plane approached the pylon. But Drew, usually with the longest and broadest lens in the group, would wait patiently, then swing in time with the aircraft, fluidly and manually focusing all the time, and “click” once.

We’d scour competing publications the following day and Drew usually produced the sharpest, best shot.

I’m pretty sure he was born on King Island, in Bass Strait, he was certainly raised there because I recall his stories about his farmer father “Eagle Eye Arthur”, who gave himself the nickname by being able to count cows with miraculous accuracy as they came crowding through the gate.

Drew worked for the Examiner in Launceston before heading to Victoria to work for The Sun in the 1970s, taking his beautiful young wife Jenny. The industrious pair bought decrepit old suburban Melbourne homes that had been divided into rental units and flats, and restored them to their former glory as inner-city family mansions.

There’s a buck in it, Drew told me. He and Jenny also fossicked in Tasmanian second-hand stores for antique brass beds, and put wanted-to-buy ads in the paper, to ship them across the strait to be sold for top dollar.

But Drew’s day job was as a lensman of rare ability and notorious charm. I can’t recall how many Melbourne Cups and VFL games he said he had covered, but it was a lot.

He liked sport but was adept at all aspects of photography. Most newspaper lensmen hate doing pictures for the social pages, believing it below their station.

Drew was in his element when surrounded by smiles, tuxedos, stockings and frocks. Everyone wanted him to take their photo.

I met Drew in Launceston about 1992 when we worked together for many years for the Mercury and the Sunday Tasmanian.

We spent thousands of hours on the road chasing ambulances, cold-blooded killers, tragic plane crashes, oil tanker spills, HIV-positive footballers, fashion models, disgraced businessmen and dodgy MPs.

I called him the Silver Fox because, about 20 years older than me, his moustache and locks were a giveaway of his advancing years, but that only seemed help attract the ladies. They loved him. Drew was charming and debonair, with a windswept-castaway look in his eye and the gift of the gab.

I had many names for him. My favourite was Monsieur Fitzbigoni because there was something awfully European — Italian or French — about his gusto and lust for life, especially after a few beers when a theatrical flourish would manifest in his actions as he told gripping tales of taking photos of the rich and famous. His yarns often ended with a self-deprecating quip, a wry grin, and a giggling fit.

We drank and smoked too much. I recall sitting at a bar in Launceston when Drew posited: “Have you noticed that with each beer this bar keeps getting taller?” Sure enough, my arms were up over my head just to rest my elbows on top of the bar and we were talking to each other about half way up a monstrous teak cliff-face. It was much later we realised the bar stools were old and dodgy and were ever so slowly sinking to the ground.

I remember the time we were eating sandwiches while on the road. He was driving when he wound down his window and spat something out. “There was a great lump of gristle in my chicken sandy,” he wailed with a look of horror. I burst into hysterics because as he looked at me with his mouth still open in shock, I could see he had actually spat his front tooth out of the car. It was gone.

Once I’d convinced him it was his tooth not gristle he had just spat out, we raced back to find the broken tooth, probably in a small moist mass of chewed bread, chicken and mayonnaise. As we scoured the roadside, an ABC TV crew, heading to the same news event, stopped. “What are you looking for?” one called. “My tooth,” Drew said, flashing a new toothless grin that stole any sense of intelligence from his face and left him with a vacant Huckleberry Finn-meets-inbred-simpleton-from-Deliverance gaze. “The dentist might be able to glue it back.”

The ABC guys, bemused, sped off after the story.

Another time I remember stepping over a farmer’s fence near the Launceston airport to investigate a plane crash at the end of the runway when my crotch touched an electric fence and sent me hollering in pain. Drew was rolling in the paddock in laughter: “I was just about to say, ‘careful, Simon, it’s electric!’” Timing is everything in humour, I guess.

I remember after a long day on the road on the East Coast at a time people were selling house and home to move elsewhere to find work, Drew started saying “Roberts” each time he saw a Roberts Real Estate sign in a front yard. Not wanting to encourage the behaviour, I ignored him. I reckon he said Roberts, with the bubbly croak of a banjo frog, 50 times before I cracked: “For gawdsake, Drew, please stop, please.”

We worked hard, often clocking in 17-hour days, and 10 or 14 days straight without a break, and after long, long days there is a light-headed tiredness on the drive home that seeks comfort in surgery-type humour. It was a way of coping with deadline pressure, and it was a damn-sight better than listening to Drew croon along with Leonard Cohen, which was always on the cards.

Drew and I covered important stuff and were committed to doing the job professionally, but all I want to remember now he is gone are the silly bits in-between that so often get dismissed as trivia. Suddenly those hilarious asides and whispered quips have become the touchstone memories of our friendship.

Life, it seems, really is what happens when you are making other plans.

At least Drew won’t have to worry about what’s happening with Facebook and journalism now he’s fled to the land of all great lensmen where classified advertising revenue still flows like rivers of gold and the deadline forever approaches for the next edition of the daily rag, which of course is the only game in town.

Vale Drew Fitzgibbon, I have never laughed as much.