IN a year that gave us the horror of MH370 and MH17, a third commercial aviation disaster seemed unthinkable.

But that all changed last Sunday when AirAsia delivered the grim news that one of its Indonesian-owned aircraft was missing on a routine flight from Surabaya to Singapore.

Travelling just two days after Christmas, there were 162 people on board flight QZ8501 — many heading off on holidays or home to be reunited with family.

Groom-to-be Alain Oktavianus Siaun was travelling with his parents and brother, for a final family vacation before his wedding.

British passenger Chi-Man Choi was bringing two-year-old daughter Zoe to be reunited with his wife, and the little girl’s mother.

Indonesian teacher Florentina Widodo was taking father Nanang to meet her boyfriend Andy Paul Chen in Singapore.

And Melbourne university student Kevin Alexander Soetjipto was on a family trip with sister Cindy and another relative.

Each had paid around $100 for the two-hour 13-minute flight with AirAsia Indonesia, considered one of the region’s safest low-cost carriers.

For the first 30 minutes, the flight was unremarkable.

But in the next 10-15 minutes, one can only imagine what the passengers and crew experienced as the flight presumably encountered severe turbulence and possibly stalled, before crashing into the Java Sea.

There were no survivors, and in one of the most heart-wrenching revelations of salvage crews, some of the bodies were found linked — holding hands as they braced for their final moments.

AirAsia boss Tony Fernandes called it his “worst nightmare” and the days that followed, the toughest he had experienced.

“My heart bleeds for all the relatives of my crew and our passengers. Nothing is more important to us,” he tweeted in a series of outpourings on social media.

Although the contents of the black box flight data recorder will reveal exactly what went wrong on board the A320-200, an array of experts has already compared the incident to the Air France crash into the Atlantic Ocean in January 2009.

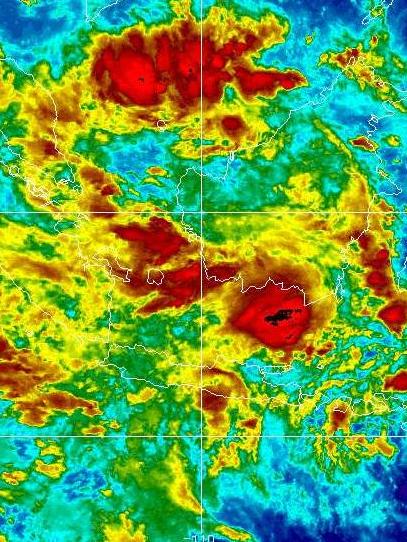

Just as that aircraft hit bad weather with catastrophic consequences, so did QZ8501 — it would seem.

But what remains unclear, is how much of a hand the pilots played in the disaster, as was the case with Air France Flight 447, where inadequate training and inexperience were identified as contributing factors.

All over the world, experts insisted that weather alone was not enough to down a modern jetliner, particularly the near crash-proof A320-200.

Early warning systems, autopilot, back-up power and a multitude of default systems all combine to make the aircraft one of the safest in the skies.

And in the very rare event things do go wrong mechanically, there are still options for the pilots to recover from bad situations.

Australian aviation expert, Ron Bartsch from AvLaw says the lack of a mayday call by QZ8501 added to the evidence that pilot error was in play.

“Obviously if the crew had suffered a situation where they were not able to control the aircraft, then they wouldn’t have been in a position to transmit a mayday call,” says Bartsch, a former head of Safety and Regulation Compliance at Qantas Airways.

“Unless there was a catastrophic event that occurred on the aircraft that had the pilots incapacitated or unable to transmit a mayday the only other plausible scenario is that they were so preoccupied to get the aircraft out of the stall situation.”

In the aftermath of the Air France crash, which claimed 228 lives, Bartsch says it would be disappointing if it is found a lack of adequate training was responsible for QZ8501.

“The only thing worse than having an accident is not learning from that accident,” he says.

“That goes for all airlines, not just the one directly involved.”

Up until Sunday, AirAsia Indonesia had a reasonably good reputation, certainly enough to get it off the European Union’s banned list four years ago.

There had been the odd runway overshoot but never had the airline lost a passenger, let alone an aircraft.

Sunday’s announcement, accompanied by radar images showing QZ8501 there one minute, gone the next, triggered chilling memories of MH370.

The Malaysia Airlines’ Boeing 777 carrying 239 people vanished from radars early into its flight from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing on March 8.

Nearly ten months later, its fate remains unknown and a massively expensive search in the southern Indian Ocean has failed to turn up any trace of the missing plane.

The two incidents have left people around the world wondering how in the second decade of the 21st century could a large aircraft simply go missing.

Technology such as GPS tracking devices have made it virtually impossible for anything or anyone to remain hidden in the modern world — how can a jetliner disappear?

The answer lies in the surprisingly archaic methods used by the world’s Air Traffic Control (ATC) network which continues to rely on radar technology first developed in the 1930s.

Primary radar — using reflected radio signals — does not extend to some parts of the world, or over oceans, and secondary radar only operates if the plane’s transponder is working.

Military radars may extend further but their reliance on lengthy antenna arrays makes them hugely expensive.

That was why it was relatively easy for MH370 to disappear from view between Malaysia and Vietnam. Once communications were turned off, including the transponder, the aircraft effectively vanished from screens.

Aircraft do use GPS but normally just to show pilots their position on a map. The information is not usually shared with ATC because of the expense involved.

San Diego-based aviation expert Hans Geber says the MH370 mystery and now QZ8501 had led him to think radar facilities in the region were not very effective.

“Most of the flight path would have been over the Java Sea, close enough to Indonesian land that modern radar should have been able to track it,” Geber says.

But Pacific Aviation Consulting director Oliver Lamb says if an aircraft is not in the air it can’t be tracked.

As it turned out, that was sadly the case with QZ8501 with wreckage located within 10km of its final position on radar screens.

Even then, the debris took three days to find leading Bartsch to suggest the chances of ever locating MH370 were looking more and more remote.

“No one knows where its last position was. It’s all based on best estimates from a few satellite pings,” he says.

“The reasons why they found QZ8501 were there was wreckage and oil slicks in the vicinity of its last known position.

“I suspect now the chances of ever finding MH370 are decreasing significantly.”

What it amounts to is an enormous amount of grief for hundreds of families worldwide.

In just three aviation incidents — MH370, MH17 and QZ8501 — 699 lives have been lost.

Other less well publicised crashes, such as that of a TransAsia jet in Taipei in July took the toll to over 1000 for 2014.

Bartsch says commercial passenger jet crashes had the potential to change how people approach flying.

“I think if it turns out QZ8501 was the result of human factors, in particular pilot error, and moreover it was a lack of training, that will be a consideration people take into account when they’re considering air travel,” Bartsch says.

“Because air travel, particularly with low cost carriers is extremely competitive and the costs are so close together, than safety would obviously become an element in people’s determination as to what airline they’ll fly.”

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As spring moves into summer what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.

Child rapist, killer walks free from prison after 38 years

A convicted child killer has walked free from prison after 38 years behind bars for raping and murdering nine-year-old Deborah Keegan in her western Sydney bedroom.