AUSTRALIAN troops faced unspeakable horrors on the beach and hills of the Gallipoli Peninsula in 1915. But they embodied a special temperament that helped them through the atrocious battlefield conditions. TONY LOVE looks into how our Anzacs survived.

THE cold, hard truths of warfare dawned quickly on the first Australians to land at Gallipoli.

Following faithfully the Allied plan to come ashore at a relatively accessible beach, but washed north by badly navigated strong currents to where the Turkish coast rose into rough-hewed hills, our young soldiers were suddenly struck by the brutality of real-life battle.

Eight months after enlistment and training in Australia, Egypt and the Greek island of Lemnos, a staging post near Turkey, they were ready for a blue — or so they thought.

“We are to see actual fighting at last,” Orderly Sergeant Benjamin Bennet Leane wrote to his wife Phyllis in Adelaide in March.

“And we are very elated on that account,” he said.

But as the invasion approached and the first four Australian infantry battalions and associated units gathered into one immense force, the men were much more aware of the danger ahead.

“We reckon to get it pretty hot for the first four days, but we have no doubt about the final success of our venture,” Sergeant Leane wrote a week before the attack on Gallipoli’s shores.

His mood, however, began to darken two days out: “I trust I will come through all right, but it is impossible to say and I must do my duty whatever it is.

“I am not afraid to die, nor am I afraid of what is to come after death,”

Numbers don’t lie

Sergeant Benjamin Leane’s keenness for the battle to begin, his sense of duty to fellow soldiers and his country, and his stoic resignation to the grimmest of outcomes are typical of that suite of Australian character traits we celebrate as the “Anzac spirit”.

But that spirit received a rude shock before many had even reached the shore on April 25 at what’s now known as Anzac Cove.

In the pre-dawn dark the first Turkish shots whipped towards the initial covering parties of Australian soldiers still in their little boats, then more fire, more and more vicious. The first men hit in the campaign were badly shaken, of course, while others headed quickly overboard where many drowned under the weight of their battle-geared packs, or also took bullets into their upper bodies, the water bloodying around them.

They were the first of the numbers game to follow, Allied casualties estimated between 300 and 400 on April 25 alone. In a week the figure had risen to 6500, a quarter dead. In the first nine days, considered to be the landing phase of the Gallipoli business, 8500 Anzac soldiers and 600 British marines were tagged as casualties, 2300 of them killed. The Turkish numbers were estimated at 14,000 injured or dead.

By the end of the unsuccessful campaign in December, the lists had become unfathomable scores. The Australians counted 8709 dead and 19,441 injured. The Kiwis mourned 2701 killed and 4752 hurt. All up the Allies registered 140,000 casualties and the Turks more than 250,000, including 87,000 lives lost.

The figures themselves are impossible to grasp. Imagine every resident in a city like Alice Springs, Mt Gambier, Nowra, or Warrnambool either dead or injured by chaotic gun or shell fire in less than a year. From the Australian numbers alone, that is what happened in Turkey in 1915.

From Verve to Nerve

The casualty figures may be shocking on their own, but they still don’t reveal anything of the abominable scenes encountered on the fire ground. The horror those fresh-faced young men faced, so keen to show their mettle and pride for a fledgling nation, soon changed their view on life forever.

“The troops had rushed into the hills full of verve that belongs to young men who had not seen much of death,” Les Carlyon wrote in his definitive book Gallipoli.

The maelstrom of that first morning perhaps made it seem more like an unruly game than it was meant to be. For the young volunteers who had never been shot at before, there were no familiar reference points. Their units had all been fractured into smaller teams without established command lines, their initial orders pointless and soon confused. Corpses piled up all around.

“Death was everywhere,” Les Carlyon wrote. “Death was where you rolled a smoke or told a joke or carted water. Day and night it was there.”

It became so much a part of the Gallipoli Peninsula landscape that remaining soldiers seemingly had to immunise themselves from the associated shock.

A man whom Benjamin Lean had been passing orders to in a frontline position ducked his head as a burst of firing was heard. Leane repeated his messages after the tirade passed, but the colleague took no notice.

“I called on him several times without response, so I crawled up to his position,” Leane recalled in his diary.

“The poor fellow had been shot through the head and was quite dead,” he matter-of-factly penned.

But Leane realised all too quickly that something inside him had shifted.

“It is nerve racking I can tell you, to see men struck down all around you, and to hear their cries and not be able to help them,” he wrote. Then only a few moments later he added: “At first these things fill you with horror, but after a while you become accustomed to them and take little notice.”

An ANZAC state of mind

The capacity to endure such nightmares was considered by many observers as most evident in the Australian soldier compared to other those from other nations.

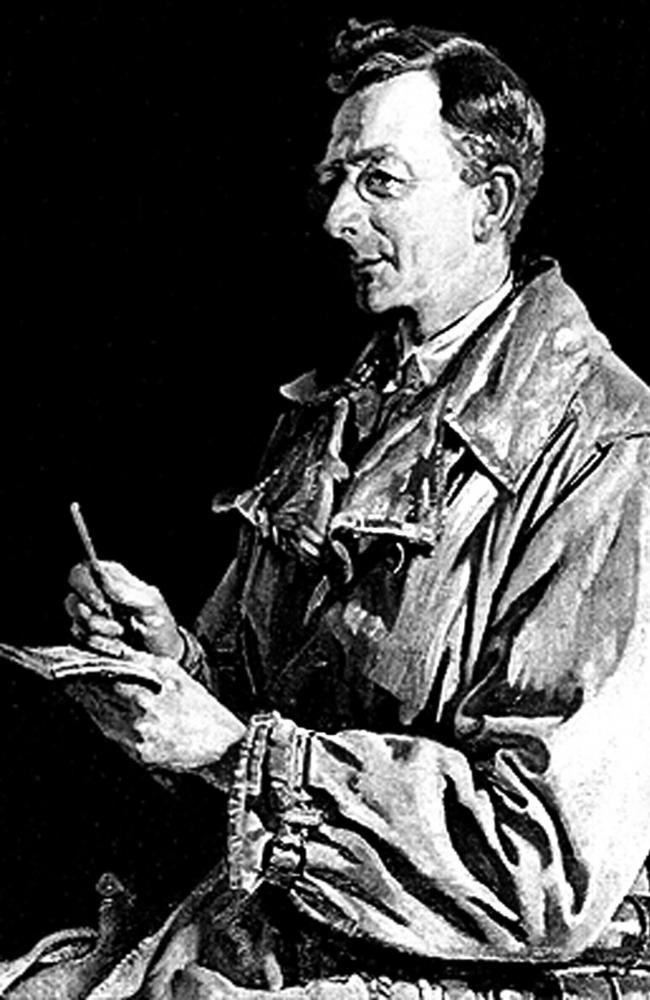

Charles Bean, our official war historian, wrote that the Australians had become clearly distinguishable from the English “in bodily appearance, in face and in voice”.

“He also displayed certain markedly divergent qualities of mind and character,” Bean wrote.

Of these he highlighted an intense nationalism and patriotism, an inherent independence and enterprise, an adventurous spirit, and greater physicality than “the general run of men” due, he surmised, by reason of our active, open-air life in the Australian climate and an abundance of food.

If this sometimes prompted a sense of “aggressiveness”, there also resulted a “vigorous and unfettered initiative”. The bushman’s existence made it necessary to solve problems on the run with little or no help, enabling prompt action in emergencies.

A lone ranger approach to the world and a true belief in egalitarianism also “endowed him with a power of swift individual decision and, in critical moments, self-control, which became conspicuous during the war,” Bean observed.

Mateship and survival

If there was one creed that distinguished Australia’s soldiers more than any other, it was that at any cost they would stand together as one.

“This was and is the one law which the good Australian must never break,” Charles Bean wrote. “The strongest bond in the Australian Imperial Force was that between a man and his mate.”

“At Cape Helles when bullets seemed to be raining in sheets, on every occasion when an Australian force went into action there was to be found men who, come what might, regardless of death or wounds, stayed by their fallen friends until they had seen them into safety,” Bean wrote.

Put all these characteristics together and a certain kind of Anzac hero emerged from the Gallipoli battleground. He was recognised by colleagues across all sections of society as a unique specimen.

Compared to their counterparts from the mother country, Army Nurse Alice Ross-King commented after witnessing hundreds of injured being delivered to hospital tents behind the lines that while “the English soldier is a very poor class”, our men were far more composed.

“All our men are mad to get back to the fighting again, but one never hears the Tommy say so,” Alice wrote.

Her eyewitness account after a week of battle reveals the ugliest of scenes and an unbelievable fighting spirit.

“The wounds are terrible … some of the injuries will mean amputation of the limbs. Most were flyblown,” Nurse Alice wrote in her diary.

“They were lying there in misery and some so weak and miserable the tears were flowing.

“I went to bed heartbroken.”

But she pointed out tellingly: “We are all suffering from shock … The boys are such bricks about it, too.”

Life and death

General John Monash, who led a brigade in Gallipoli and went on to command the Australian infantry in France, called such a brave temperament the Australian private’s “glorious spirit of heroism”.

It stemmed from a distinct upbringing back home, he said, citing a respect for democratic institutions, a strong pride in a young country, an education that inspired young Australians to think and act for themselves, and a national heritage expressed in an “instinct for sport and adventure”.

When it came to the men’s physical capacities, Monash believed the Australian Army was composed of the flower of the continent’s youth. And psychologically, their imagination readily bloomed.

“War to him was a game, and he played for his side with enthusiasm,” Monash wrote about the men almost as one.

“His bravery was founded upon his sense of duty to his unit, comradeship to his fellows, emulation to uphold his traditions, and a combative spirit to avenge his hardships and sufferings upon the enemy.”

But no matter how enterprising, patriotic, or adventurous those first ANZACs were, Gallipoli’s horrors remained burned permanently in thousands of Australian souls.

With so much death and injury surrounding them, too many soldiers began to feel the impact of the very closeness of that catastrophe on the ragged hills of the Turkish peninsula.

Placed at the centre of the greatest action they would ever experience, its effects were heightened beyond compehension.

“You had to know you were alive here,” Les Carlyon wrote. “(Death’s) nearness made you feel so thrillingly alive.

“Many who outlived this place could not settle down when they returned home,” he observed.

“They had never been so aware they were alive as when they were here, close to death.”

But once home in Australia so many of those who did survive were changed forever. Having experienced the darkest truths of warfare, nothing could be the same again.

- All pictures thanks to the Australian War Memorial

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As spring moves into summer what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As spring moves into summer what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.