DRIVE around Sunshine North and you’ll find them. One street has four houses where people have died. Around the corner, a son blames himself for the death of his mother. RUTH LAMPERD reports on how white dust has torn a Melbourne suburb apart.

ALLAN Brander was nicknamed Snowy because his hair was pure blond. You couldn’t see the white dust settle on his head during the long days he played with mates in the Sunshine North factory dump yard. But it dusted his clothes and caked his feet.

There were no fences around the factory — two footy kicks from his house — to keep Allan and his young mates out. No signs to warn of danger. The white mounds of dumped asbestos were irresistible, hours of fun that stretched into days.

None of the people who lived there knew what those puffs of powder could do. Why would they?

Five acres of the stuff formed little hills and gullies perfect for young boys on bikes or barefoot.

They’d throw it at each other; dig in it like it was beach sand.

Kids before him did the same. And kids afterwards. They’d walked through the factory property on the shortcut to and from school. Their mums pushed little brothers and sisters in prams past the Wunderlich factory front gate. On some dry and windy days they could see the cloud of dust rise over their suburb.

Many of the mums had husbands working shifts at Wunderlich. We hear about the deaths of men like these. Asbestosis, mesothelioma and lung cancers are common for workers who breathed in the deadly fibres for years, five days a week.

But Allan was just a kid. He was just playing. He was exposed very young. It lay asleep in his body for 40 years. It chopped him down at 58 when he hadn’t yet fully retired.

Allan died five months after doctors told him he had mesothelioma. It was a painful end. It killed him hours before he was to give hospital bed video evidence for his legal case against the asbestos company.

His son, Damian, spent those last months with his father. “The disease ate him alive,” Damian says. “If I grew up there, I’d be concerned about my health now.”

He is appalled at the Wunderlich and CSR men who should have known a whole suburb was in danger. The industry knew in the 1920s how asbestos dust could make their workers sick.

But these weren’t people who worked in asbestos factories or mines. They weren’t even people who cut up fibre board in home renovations in the years that followed.

The folk of Sunshine North did nothing more than live and play and breathe in a suburb where the ground and the air could kill them.

STAND outside Allan’s childhood home and head east towards McIntyre Rd. You pass four Barwon Ave houses where people have died from asbestos-related diseases.

Turn left, head up McIntyre and right into Berkshire. A man who lived and grew up on the right died recently from mesothelioma. His family don’t want to speak.

Take another right into Berry St. A three-bedroom house halfway along had 12 children and two adults living there in its most crammed of times.

Bill Sharp was one of them. His sister and mother died from mesothelioma. His brother, Robert, now lives in South Australia and has asbestosis that makes him very ill.

Bill himself has scarring — pleural plaques — on his lungs. “They give me a lot of problems. I’ve had a collapsed lung, fluid on the lung, pneumonia and now a permanent cough. I’m going to have it checked soon and I’m just hoping I don’t have the same as my sister and brother,” he says.

“No money in the world would be enough if I got ill because I’ve seen what it does.”

Marie Casha is spending her later years struggling with asbestosis. At 76 she lives in Buckley St still. Her brothers, uncles and later her sons would come home after work at the Wunderlich factory and drop their overalls there for her to wash. She did this dutifully for years.

And at just 144cm she was a walking dynamo. When she was young she’d cart her own kids and two of her brother’s for miles around the area. She’d always pass the factory and drop off lunch or dinner for relatives at the factory.

Her son, Jimmy, worked there for a short time in the ‘70s. He remembers sticking asbestos health warnings on the products.

“At one point, as I breathed in the dust from the factory, I thought: ‘Hang on, if we’re warning the people who buy this, what’s it doing to me?’

WUNDERLICH was the “go-through” place in the suburb back then. People who lived nearby would always walk past or around it to primary or high school, to the bigger shops south in Sunshine, to the shopping strip in McIntyre Rd, to Albion railway station.

From aerial shots taken in 1956 you can see diagonal tracks worn by foot traffic through the adjacent vacant blocks.

Every one of those thousands exposed is at risk even 40 or 50 years after they lived there.

The Sunday Herald Sun learned of the pattern of environmental exposures through a lawyer.

Margaret Kent has worked with hundreds of asbestos victims, who have fought and won compensation from the company — CSR — that bears the brunt of the Wunderlich sins. CSR bought Wunderlich in 1969 through its subsidiary company Seltsam.

Kent lives in the inner west. When she drove through Sunshine North she would see street names that rang work bells. Back in the Slater & Gordon office she rifled through files of cases colleagues in the law firm had won or settled for about 15 victims over a handful of years.

They all lived within 1km of the factory. None of them had worked in the industry.

Was it coincidence? Unlikely. About 10 more cases, some which have never sought legal action, emerged after a four-month Sunday Herald Sun investigation. New cases are expected for years yet.

A scientific diagram — using Environmental Protection Authority software — show the possible contamination plume correlates to the homes where the deaths and illnesses had occurred.

But it’s likely the contamination from Wunderlich was more insidious, that it went further afield than mere street addresses.

Kids came from neighbouring suburbs to a vacant block of grass next to the factory. The North Sunshine Soccer Club’s under-14s, 16s and 18s trained there in the late 1960s for a year or two. Those boys would have breathed in the dust.

And some students from St Albans High School copped an even bigger dose. A 1956 school magazine report spoke of its “forms 1B and 1D” visit to the Wunderlich factory.

“The school appreciates the willingness of the firms to arrange these excursions,” the report sang its thanks. Wunderlich held itself tall as a righteous corporate citizen.

Industrial hygienist David Kilpatrick has interviewed more than 7000 people with asbestos exposure since 1977. He says there is evidence asbestos companies had policies not to employ workers younger than 35. (Some believe this was in the hope that old age would kill them before the asbestos).

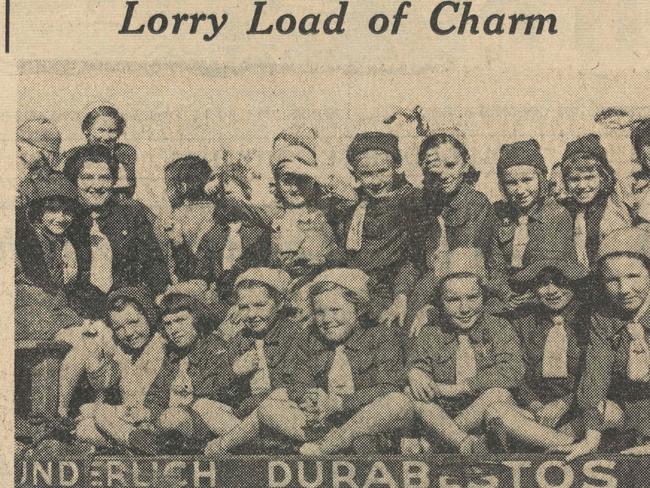

In 1951, at least 20 Brownie Guides were photographed sitting on the back of a Wunderlich Durabestos truck in Sunshine’s street parade when it was declared a city. A fleet of trucks like these — probably the one in the picture — daily transported asbestos boards to builders’ sheds around Melbourne.

And one elderly Sunshine resident recalls scouts and their parents delivering old newspapers to the factory for recycling into their asbestos fibre boards.

These things may not seem important. But they are. All the experts agree — there is no known safe lower level of asbestos exposure.

MICHAEL Kottek holds the picture of the “Lorry load of Brownies” and shakes his head slightly. He knows asbestos well. Not much surprises him now. He has prepared more than 1000 reports for victims of asbestosis and mesothelioma.

Victims lodging claims for compensation will see him before they lodge a claim. It’s his job to work out where and how much exposed.

Twice he has taken samples from ceiling cavities of houses just north of the Wunderlich factory. The latest was just a month ago. Both samples revealed asbestos dust that you won’t usually find in houses where the Wunderlich factory was not.

He wears impermeable protector coveralls and mask as he disappears into the ceiling manhole. The first one he tested, in Barwon Ave, was to gather evidence for a case where a man who grew up there died from mesothelioma.

The second came from Cranbourne Ave, the next street north. He scrapes off half a centimetre of grey dust from a horizontal rafter, undisturbed for decades.

Kottek is no alarmist. But he is concerned at the presence of the asbestos in people’s roofs. Maybe there is more in backyards.

“There is a small residual risk that the public are not aware of. The (Brimbank) municipality has not done anything to manage that. I would welcome a bigger sampling program to see how widespread the contamination of ceiling spaces has travelled.”

And he isn’t alone in urging people who might have been exposed in the Wunderlich years to be tested for asbestos-related diseases.

“I saw a fellow today and his GP hadn’t diagnosed it initially. Some treatments are available to slow the progress of some of these diseases, so early diagnosis can be beneficial,” he says.

The problem is this: most people who were environmentally exposed and go to the doctor with a crackling sound in their lungs don’t answer “yes” when asked if they came into contact with asbestos.

Doctors need to ask the right questions. Patients need to tell their doctors the right things. Often neither happens.

Kottek is concerned about the state of the public land between the back of the old factory property and the train track. Asbestos fibres sit in clumps on the surface. Broken pieces of board are everywhere.

He believes it should be cleaned up properly. When sample tests confirmed contamination he was compelled to write straight away to the council instead of waiting for the test results to be published in the Sunday Herald Sun.

MAREE Munro lost her husband to mesothelioma when he was 52. Their daughter, Paige (both pictured above), lost her dad at 11. To Maree it is inconceivable that the Wunderlich contamination — so serious when her husband was growing up — is still a problem.

Paige can’t talk about her father without shedding tears. She was his only child, a daddy’s girl, the one he didn’t think he’d have.

Before he died he won compensation from CSR. Maree says he was a man of few words but before he died, he wrote a chilling picture of the innocence.

“There were mounds of asbestos which were 6-10-foot high, it was like piles of snow. We would run up and down these piles of snow and roll in it and then throw clumps of asbestos at one another. It was great fun … It was a place where all the local kids went, there weren’t a lot of houses in those days and it was a terrific playground.”

Doctors found his mesothelioma by chance, when he was treated for blood clots. He didn’t have symptoms for a while and stayed working for two years after he was diagnosed. He lived a further year after he stopped work.

Maree, whose first husband had left her a single mother with two young children, was left again to raise another child on her own.

“It makes me angry. This stupid stuff — they knew it was dangerous and they did nothing about it,” she says.

Her late husband was one of the Barwon Ave boys. His big brother was Hugh. Lea Muir from next door, Hugh and Neville Young up the street always mucked around together.

They’d play marbles in the mounds behind the factory. They’d skate over the crust on top of the asbestos as though they were skiing. They’d mix it with water to make snowballs — perfect for boys’ wars.

The three would cobble together metal sheeting sealed with a water-asbestos mix and float in them or sink in the nearby creek.

Some weekends they’d barely slip home for food because they were back out mucking around in their suburban snowfield.

While Lea was playing in the Wunderlich yard, his little brother, Gary, would drag empty hessian bags two at a time from the factory to his backyard. Those bags were used to transport the asbestos fibres to the factory from mines like Wittenoom in Western Australia.

Gary (above outside his Barwon Ave house) and other young friends would drape them over metal frames and make cubby houses along the back of their wooden fence. They’d walk the dust through the house on their shoes.

Jean Luke was the third-youngest of Greg and Hugh’s five siblings next door. She remembers picking up small pieces of asbestos, drawing out hopscotch squares and using them as pebbles in the game.

She recalls catching a lift on the Wunderlich draft horse, which would pull dray-loads of sheeting offcuts and sweepings from the factory floor down to the dumping ground.

They’d cut through the property on their walk home from school. “The old horse and the man who looked after it were always white with the asbestos dust. He’d sometimes give us a lift to the front,” Jean recalls.

The white dust was everywhere. A film of it would settle on the Barwon Ave window panes after a windy, dry spell.

A few of the families had cars. If they left their windows open, the dust would collect on their dashboards.

THE families of Barwon Ave might have suffered most, but it’s clear the impact splashed across many streets further afield.

It’s easy to see how. Consider the life of this typical young boy who grew up in Berkshire Rd. So much of his time was spent playing around the factory, or walking past it.

He would play in the white at the back of Wunderlich and on the nearby train tracks. He’d play cricket, soccer and football on the block opposite the factory front on McIntyre Rd. He would walk to both Sunshine North Primary School, and later Sunshine High School, past the factory.

He died of mesothelioma at the age of 44. His family neither willing for the Sunday Herald Sun to identify him nor to be interviewed.

Another man who died from mesothelioma in his early 60s was exposed to Wunderlich asbestos as a telegram boy. He would ride his pushbike up and down McIntyre Rd in his teens.

And Jim Trickey’s sister, Joy, died at 79 from asbestosis. They lived south in Ridley St, but often passed by the factory. Doctors discovered during open heart surgery that Jim had dark patches on his lungs. It was asbestosis. Much of his life is now spent managing his health.

And Roy Caulfield would deliver roofing screws to the factory. He lived in Cumberland St. He remembers waiting in a line of trucks to unload for three-quarters of an hour. You had to take your turn.

“It was all dusty. There was no airconditioner in the truck, so I’d wind the windows down and dust would just come in,” he says.

Roy lives with asbestosis. It hurts him to breathe. Both lungs are sore, aching constantly. He is breathless and husky sometimes when he’s just sitting. His brother, Jim, died from lung cancer before the asbestos dangers became so commonly known. He’d worked in a nearby factory and believes the asbestos, too, claimed him.

The cases go on. The stories are similar. But none were so cruel to hear as the man who couldn’t stop feeling like he’d killed his mum.

EDDIE’S dad gave him an 80cc Kawasaki dirt bike when he was still in primary school. He was one of the lucky ones. In the 1970s most of his schoolmates had pushbikes.

He’d lived with his parents and two little sisters a quick squirt on his motorbike northwest of the Wunderlich factory. In those days you could travel by paddocks all the way to Altona.

Police didn’t pull up 11-year-old kids for riding unlicensed and unregistered vehicles. As long as they stayed out of trouble, they were fine.

“We were told the paddocks were Crown land. It probably wasn’t, because every now and then someone would come and chase us. They never caught us though,” Eddie recalls.

He perfected bike stunts in the back of the Wunderlich factory. They would build ramps out of leftovers in the factory yard. “They’d actually leave stuff around for us to do something with it.”

The white mounds were perfect take-off points for fancy jumps. And when they did doughnuts in the dry dust there’d be a white-out, like a blizzard.

The family house was small. Eddie would walk in the back door, into the laundry, and strip off his dusty jeans, jumper and jacket. Dump them on the floor, as kids do.

His mum would handle them there. She’d be washing loads of his stuff because he always came home dirty or dusty from his riding. He wasn’t allowed to walk it through their house.

Three years ago, at just 65, Eddie’s mum died from mesothelioma. There was nothing left of her in the weeks before she died. CSR paid compensation for her pain and suffering. By the time settlement came, she was gone.

So far, Eddie hasn’t had health problems. He knows he’s in the high-risk group for asbestosis. Now, at just 48, he’s a prime candidate for mesothelioma. It’s been that magic 40 years since his exposure. It’ll either get him or it won’t.

“I haven’t had tests, for a number of reasons, and one of those is I’m petrified of the results,” Eddie says.

He talks only once, by phone, to the Sunday Herald Sun. He didn’t confirm his name could be published and he wouldn’t return any more calls. Eddie is not his real name.

Eddie didn’t put the asbestos on the ground for every Sunshine North kid and adult to breathe in for decades. The Wunderlich and CSR executives were the ones who should have stopped it.

Yet he still responds, incredulous, at the thought he’s not to blame. He can’t possibly feel responsible for his mum’s death, can he? He was just being a kid.

But he does. “If only I was one of those quiet kids that sat at home and read books or looked at the stars at night,” he chokes out.

“She’d be alive now. My mum shouldn’t have died how she did. Nobody deserves that.”

------------------------------------

Vision: Jason Edwards

Interactives: Shane Luskie

Video editing: Craig Hughes

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Child rapist, killer walks free from prison after 38 years

A convicted child killer has walked free from prison after 38 years behind bars for raping and murdering nine-year-old Deborah Keegan in her western Sydney bedroom.

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As spring moves into summer what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.