Bold sphinxes. Enticing nymphs. A menacing rape-scene mosaic. While these finds have amazed, they’re yet to inform. But the evidence is mounting, and we may soon know who lies beneath the mysterious Amphipolis mound.

IT may be Greece’s greatest ancient monument: A 2300-year-old, 590m-diameter burial mound containing a mysterious mix of structures.

Excavations since August have exposed a myriad of artistic wonders.

Delicately crafted, scantily clad female-formed columns. Piercing eyed, female-headed sphinxes.

Most prominent is a masterful mosaic depicting a supernatural rape scene.

3D RECONSTRUCTION: See the walk-through of the tomb at the bottom of this story

But it is a scattering of bones and a few faded paintings which now have archaeologists excited. These may contain the final clue as to the identity of the tomb’s occupant — a person who may have direct ties to the legendary Alexander the Great.

It is the idea that the mound is linked in some way to Greece’s greatest hero — Alexander the Great — which has the nation on the edge of its collective seat.

The national hero still inspires great pride and passion, and the pressure on the archaeologists to produce results is immense.

But the amazing artwork has itself inspired detractors: It’s so advanced that some have cast doubt that it really dates from the era of legendary general’s death in 325BC.

Instead they insist it must belong to one of his successors, or may even be a Roman monument attempting to tie their own achievements to that of the legendary general.

Now the evidence is mounting against the detractors. Coins showing the great General have been recovered in the tomb, and heavily faded artwork appear to show scenes reminiscent of Mycenaean fertility cults.

As the penetrating eye of science is turned on the faded images and decayed bones, much of Greece holds its breath: Is this the tomb of Alexander’s mother, Olympia?

The answer, whatever it may be, will no doubt become one of archaeology’s greatest discoveries of 2015.

IT was touted as the biggest, most significant archaeological find in decades: Six months later, what have we learned from excavations at the massive Amphipolis complex?

The first three rooms have been exposed, but we still don’t know whom the tomb was built for, or even if it was a tomb: It could have been a memorial.

But a new scan of the Amphipolis mound, known as Kasta Hill, indicates the massive ancient monument may contain much more.

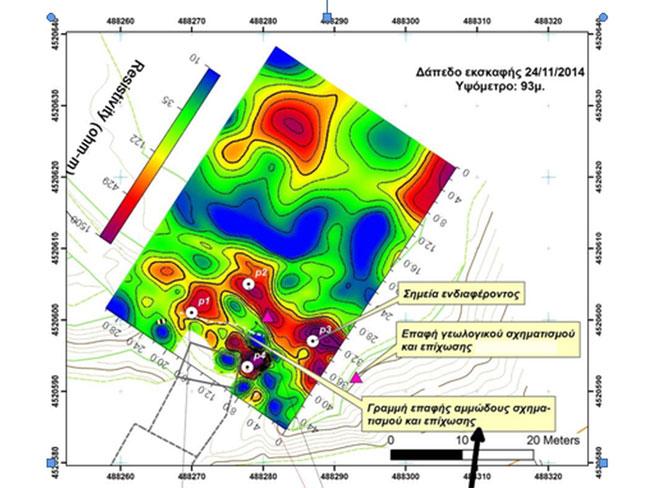

The Greek Ministry of Culture yesterday released the results of a geophysical (ground-piercing radar and electrical) survey. The extensive study, which began on November 11, is still undergoing computer processing.

So far, four areas of ‘especially high electrical resistance’ have been identified, indicating the possible presence of further structures beneath.

These new “hot spots” have been identified as priority sites for anticipated new excavation efforts in the next Northern Hemisphere summer.

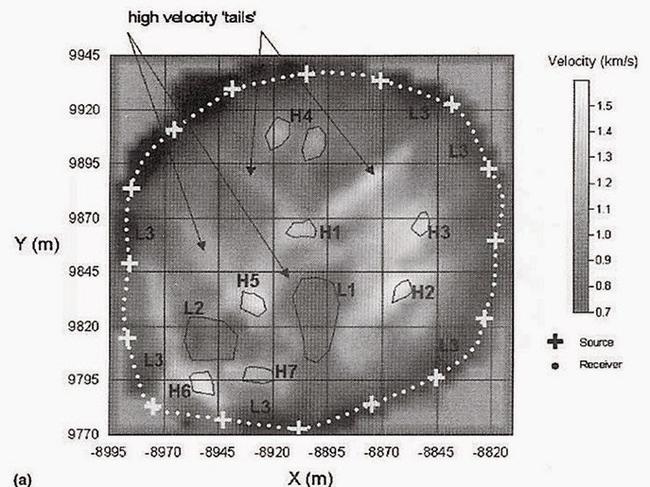

The geophysical survey results follow a 1999 seismic tomography study of the mound — essentially measuring the distortions of sound passing through the earth to build up a subterranean map. This study, abandoned due to lack of funds, also suggests there may be a series of structures underneath the soil and rubble.

If confirmed, such structures will resolve what archaeologists have been suspecting since this year’s dig began: That this remote hill is in fact a complex set of separate constructions — not just an enormous earth-covered mound for a single burial chamber.

The already excavated tomb is also scheduled to undergo further geophysical scanning, the ministry states, in order to discover any further concealed secrets.

The Greek archaeologists examining the Amphipolis tomb complex have expressed their belief that it may have been the work of a single architect.

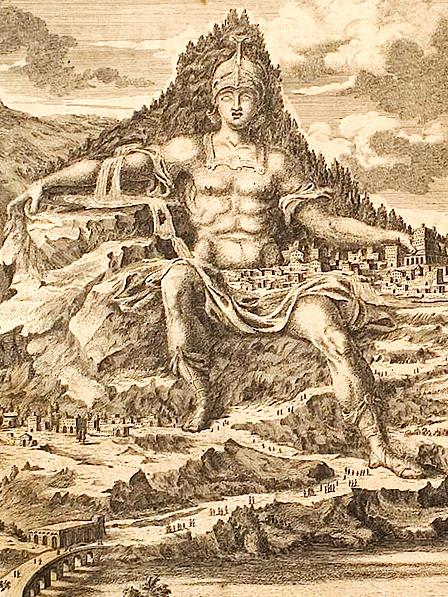

One candidate for the enormously ambitious project is Alexander’s personal architect, Deinocrates (which translates to Master of Marvels). The Greek Reporter argues he had the vision, having already proposed sculpting the whole of Mount Athos into the reclining form of the great general.

The only complication is that Deinocrates primarily worked in Egypt, on the construction of the city of Alexandria. But links have been drawn between the distinct edging of stonework found in both locations, as well as similarities in the local ancient road plan, to support the theory.

Likewise, the imposing mosaic of the second chamber also has declared astoundingly intricate and detailed for the era.

Despite missing a large circular section at its centre (archaeologists say many of the fragments have been recovered), it is clearly the work of a master artist.

Then there are the faded paintings found on the architraves of the third chamber.

Pictures released earlier this month appear to show a man and a woman, wearing red belts or sashes on golden loincloths, dancing among bulls. Another image shows a winged goddess standing between an urn and a brazier. The chamber’s ceilings were covered with rosettes.

According to The Greek Reporter, this imagery has been linked to another royal sanctuary of the era — in Macedon. The Sanctuary of the Great Gods on Samothrace was an island complex associated with bull sacrifice and heavily adorned with stone rosettes. Also found there was the famous statue of Nike — the winged goddess of victory.

It was also a cult strongly associated with Alexander’s mother and father.

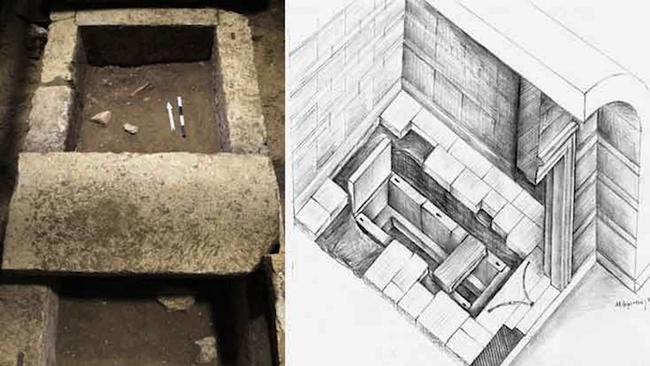

Amid the most significant find announced during the excavation was that of a scattered skeleton and fragments of a wooden coffin decorated with bone and glass in the third chamber.

“The bones were found inside and outside the burial pit,” a Greek government official told reporters in November. “The skull was quite some distance away from the pit, the lower jaw was just outside the pit and the largest part of the skeleton was inside the pit. A close look shows that the legs and arms are almost intact, rib bones and parts of the spine as well as the pelvic bones are in fragmentary condition, therefore it is impossible for archaeologists to say if they belong to a man or a woman.”

Despite the supporting assertion by chief archaeologist Katerina Peristeri that she has no idea as to the identity of the skeleton, speculation is running rampant.

The remains, said to be still covered in earth to ensure their preservation, have yet to be reassembled to a suitable state for the identification of key gender features.

The Greek government again last week sought to dispel rumours that the bones had already been identified as belonging to a 54-year-old woman. Such details would place the tomb squarely in the domain of Alexander the Great’s mother, Olympias.

MOTHER OF A LIVING GOD? The Amphipolis mosaic explained

Speculation surrounds the fact that the skeleton’s pelvic region appears to have been particularly heavily fractured. Olympias was stoned to death at the order of usurper General Cassandros in 316BC

“The study of skeletal material, found in the fourth place of the burial monument on the Casta hill, is commissioned to a team of scientists from the Aristotle and Democritus Universities … The analysis of this material is part of a broader research program, which includes the holistic approach of a sample of about three hundred skeletons, coming from the area of Amphipolis and chronologically cover the period from 1000 B.C. to 200 B.C”

“The results — such as sex, age, stature — the macroscopic study of skeletal material from the fourth place of the burial complex, will be announced in January,” the statement reads.

hief excavator Peristeri has a much more pragmatic point of view: She states that the lion statue which once sat atop the mound was male and that the wall encompassing its base was once covered in engraved shields. This indicates the mound was made for one of Alexanders’ generals, she says.

Others point to a legend recorded by the Greek historian Plutarch which states King Philip, Alexander’s father, dreamt he had put a seal of a lion upon Olympias’s womb. This was interpreted by soothsayers as predicting she would bear a bold and lion-like son.

Placing a statue of a lion above a pregnant belly-shaped burial mound fits this imagery.

But the answer may be amid the remains of the burial chamber itself.

Unreadable traces of inscriptions have been found on the columns and marble plates about the stone tomb in the third chamber. These will undergo ultraviolet analysis in an effort to trace their outline, and hopefully a name. The process is scheduled to start early next year.

Alexander the Great swept through Europe and Asia on a conquest like no other seen before his time. Nothing could stop him — except possibly poison, or more probably a terminal bout of typhoid fever.

His untimely death meant wrack and ruin for his fledgling empire. His generals immediately set about carving out pieces for themselves.

The body of the great general is said to have been preserved in a vat of honey before setting out for his homeland, Macedonia. It would be diverted several times before finding its final resting place, somewhere near the city erected in Egypt in his name — Alexandria.

The location of his tomb has since been lost to history.

Left struggling to hold the strands of empire together was his mother, Olympias. A devoted follower of religious mysteries, she had been divorced by Alexander’s father — King Philip II after a 20 year marriage. She, and Alexander, had been restored to power after his murder.

But the queen frequently clashed with the trusted adviser Alexander left behind as his regent for Macedonia: General Antipater.

On Alexander’s death, Antipater’s son — Cassander — wanted the crown.

Olympia asserted her authority as the regent for Alexanders young son. She then sought to strengthen her hold on power by marrying Alexander’s sister, Cleopatra, to a succession of generals opposed to Cassander.

An attack on Cassander’s corner of Macedonia at first appeared successful with the rout of his army. But a surprise counter-attack toppled Olympia from the throne and Cassander arranged to have her murdered. Alexander’s wife and son, Roxana and Alexander IV, were imprisoned at Amphipolis where they were later executed.

The stunning scale of the new archaeological discovery has inspired recession-wracked Greece, harking back to an era when Alexander the Great ruled half the known world.

This fascination has been seized by a government desperate for any morale-building leverage it can find.

As a result, it has thrown significant funding at the excavation of the monument — and its promotion.

Such is the excitement that full 3-D reconstructions of the tomb was being produced even as excavators advanced.

With digging completed for the season, a full digital reconstruction of the sphinx-guarded entrance, the female caryatids supporting the inner door and the elaborate mosaic of the main room has now been released.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Here’s what you can expect with today’s Parramatta weather

As winter sets in what can locals expect today? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As winter sets in what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.