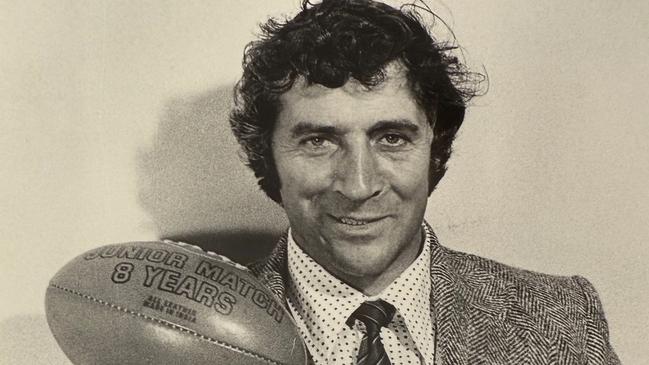

Dad’s final lesson: Tribute to Peter Bevilacqua

His father, former Carlton player Peter Bevilacqua, believed sport was a metaphor for life that taught how to win and lose, writes Simon Bevilacqua

Tasmania

Don't miss out on the headlines from Tasmania. Followed categories will be added to My News.

My father died this week.

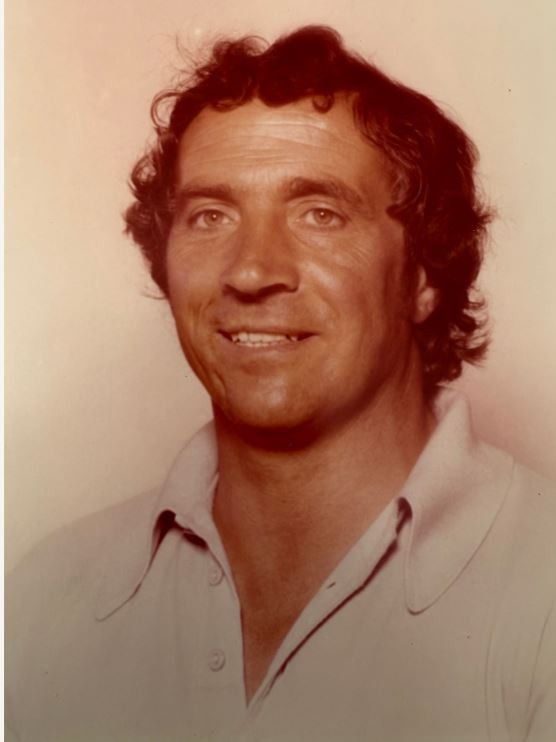

Dad was 91. He led a remarkable life. His achievements are worth celebrating, but this is not an obituary, more a reflection. My loss is at a deeper level than his accolades or successes or failings.

As I sat by Dad’s death bed on Monday, he lay perfectly still. I was not, as I feared, repelled or upset by his lifeless body. He looked dignified and beautiful. He was a handsome man, but in death he had garnered an intangible grace. He looked ancient, older than any person I have ever laid eyes on. And although he was gone, I felt a flicker of his spirit lived on … in me.

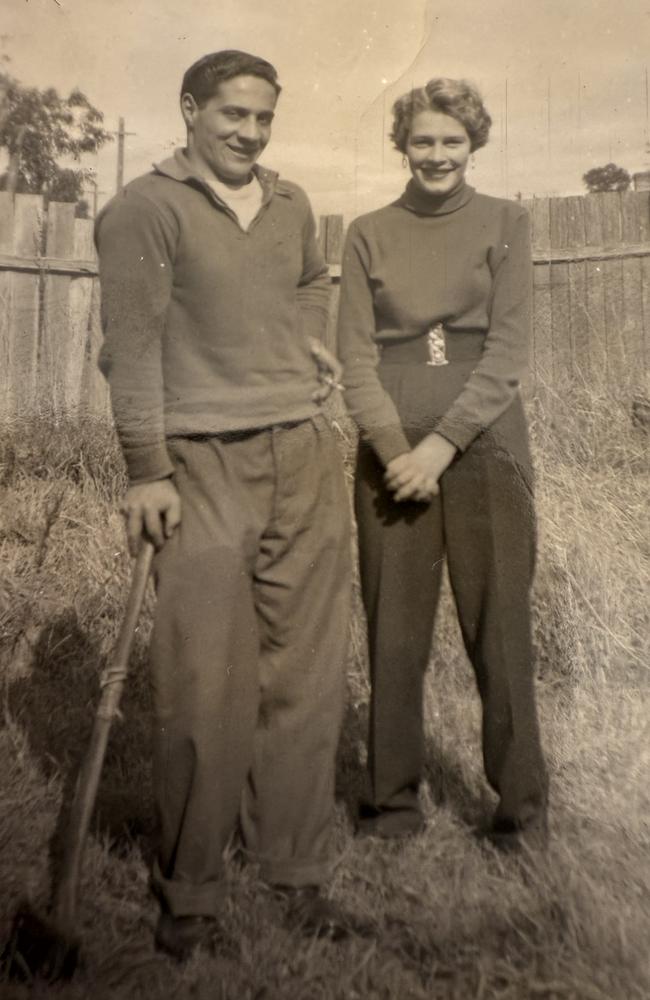

Dad was born in San Marco in Lamis, a small town perched on a mountain plateau in central southern Italy, which is dominated by a 16th century Capuchin monastery. The stone foundations of the friary date back to the year 1000, and there is a written record of monks living the monastic lifestyle there as far back as the 6th century.

Dad’s brother Mick told me that on the morning his mother packed up her four boys to leave their home in Italy and to join their father in Australia, he was taken at dawn to the monastery to be Confirmed. The priest was Padre Pio, who is said to have received the stigmata, where the crucifixion wounds of Jesus appear bleeding on the hands and feet. Pio was canonised in 1999.

I have childhood memories in Melbourne of Dad’s mum counting rosary beads. I recall gilt-framed portrayals of Mary and Jesus and crucifixes on walls and a sombre religiosity hanging like incense.

As a non-practising Anglican, Mum was not allowed to marry in the church and she and Dad had to go outside to make their vows. She had to promise her children would be raised as Catholics. When I was a teenager, I once mocked Dad’s faith in Mum’s presence. She defended him, saying she admired his belief and that I should respect it. Mum does not recall the conversation, but I never forgot it.

Until recent years, Dad never missed Sunday mass. In that sense, he was religious but, apart from teaching me to pray when I was a boy, I don’t recall him proselytising or even speaking of his faith.

He talked sport, not just scores and results; the philosophy, psychology and sociology of games. He preached from the Gospel according to Frenchman Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympic Games. Dad believed sport could channel anger, hate, frustration and aggression into socially acceptable forms of competition governed by rules.

He believed in sportsmanship. Sport was a metaphor for life that taught how to win and to lose; to train and prepare; to focus amid the storm; and to overcome setbacks.

He loved telling the story about John Landy stopping mid-race to check on fellow competitor Ron Clarke who had fallen during the 1956 Australian Mile Championships. After helping Clarke to his feet, Landy rejoined the field 30m behind, sprinted around the outside and won.

Weeks before Dad died, his grandson, Matt, competed in the Shannon Eckstein Ironman Classic in Queensland. Already battling advanced cancer, Dad had suffered a stroke on Christmas Eve that had left him with only the use of his right hand and arm. Otherwise, he could barely move.

He received the last rites in the first week of January, but lived for two months, heavily medicated, and often confused and frustrated. He managed to text Matt’s brother Joel with a simple message: “Just enjoy it and win it.” Joel passed it on to Matt moments before the start. Despite competing with a gash to his foot that required stitches, Matt triumphed. Dad watched the replay over and over again.

The last months of Dad’s life were challenging. He approached death gingerly, avoiding looking it in the eye. He devised strategies to deter it and they worked for a time, until the next blow inevitably derailed his efforts. With each step, his dance with death became more like the final retreating moves in a chess game, piece-by-piece, move-by-move, his options for survival diminished.

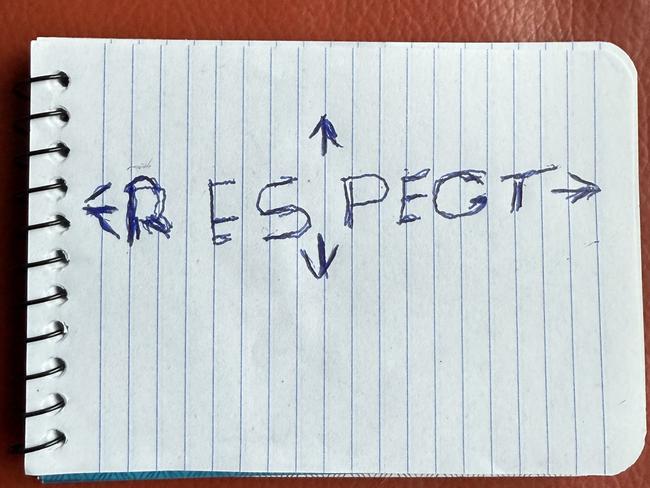

In the final week or so, he became eager to recount his life. He asked me to buy him a notebook and set about writing.

With only one working arm, a hand that could not grasp, a body that was limp, and rapidly diminishing motor skills, it was impossible. Mum told me he tried for most of the day, but achieved just one word. He kept trying for days. I said I would record an interview with him. He said he would continue making notes and we could start next week.

He died the next day.

I took the notepad home and, alone in my study, read it. On the first page was one word. He could not pen a straight line. It was scratched in feathery strokes that made the general shape of each letter. It said “Respect”. Above the word was an arrow pointing up; below it, an arrow pointing down; at the end, an arrow pointing right; and at the start, an arrow pointing left.

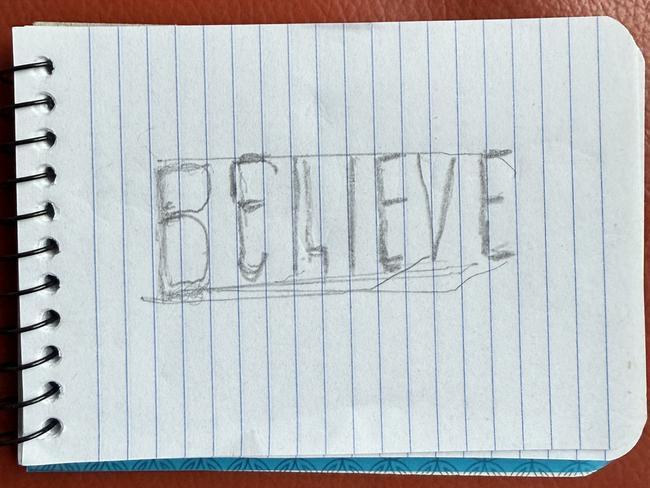

I turned the page. Another word, in block letters almost like calligraphy: “Believe.”

The rest of the pages were blank. I was mystified. There, in two words, was his philosophy – respect all around you and believe. He did not define what to believe nor limit what to respect. It was a prescription for life.

His final words were akin to the Japanese death poems that have been written for centuries by Zen monks in the final days of their lives.

Dad was a teacher.

— Simon Bevilacqua worked in Tasmania as a journalist for more than 30 years.