It’s a dubious title to hold, but Tasmania may just be the diving death capital of Australia.

The “horrifying statistics” paint a grim picture – Tasmania has about four times the national rate of diving deaths per capita, with about one fatality annually among recreational divers over the past three decades.

Among those statistics, a stark line can be drawn: all of those deaths are among recreational divers; no professional divers have died in Tasmania over 30 years.

For the recreational divers, some years are worse than others – like this year.

In a sombre start to 2024, between January and April, four recreational divers have already died in Tasmanian waters.

A paradise for divers

Abalone, scallops and rock lobsters are just some of the treasures that can be collected in Tasmanian waters.

Tasmania is known for its natural beauty, as well as its abundant seafood, with both locals and interstate visitors lured by the prospects of bringing home a premium haul.

Researchers say for its size, Tasmania has a large recreational diving population – with potentially 20,000 non-commercial divers in the water each year.

While it’s easy to see the appeal, the recreational diving industry is largely unregulated – meaning anyone can buy a hookah diving system off Gumtree or Facebook marketplace, and take to the water without any training or a licence.

Even scuba diving, which does require a certificate before a diver can get their tanks filled, can be problematic – with no annual health checks required.

The horror stories are everywhere – scuba divers running out of air after consuming vast amounts of alcohol to “stay warm” underwater, or taking the ocean while on a cocktail of prescription and illicit drugs.

Unsafe hookah equipment has been blamed for multiple deaths.

Free diving, where a diver simply holds their breath while plunging the water to collect seafood, also carries plenty of risks – especially when done alone or without using the tried-and-true “buddy system”.

When something goes wrong, divers can end up with serious – or fatal – injuries.

These include drowning, decompression illness or “the bends”, ear or lung pressure trauma, arterial gas embolisms, or carbon monoxide poisoning.

Dangers of the deep

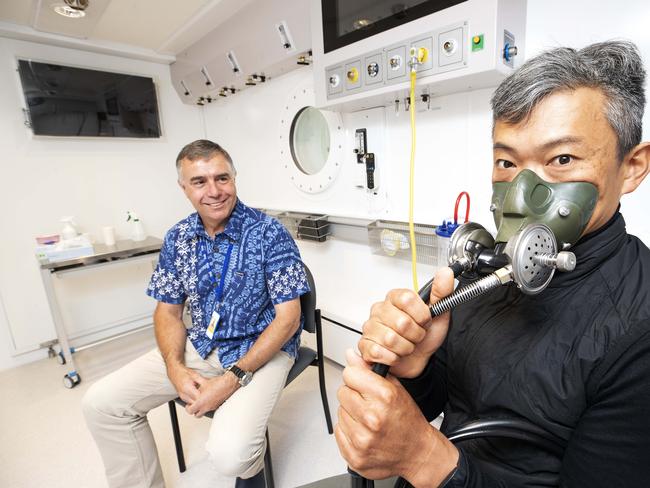

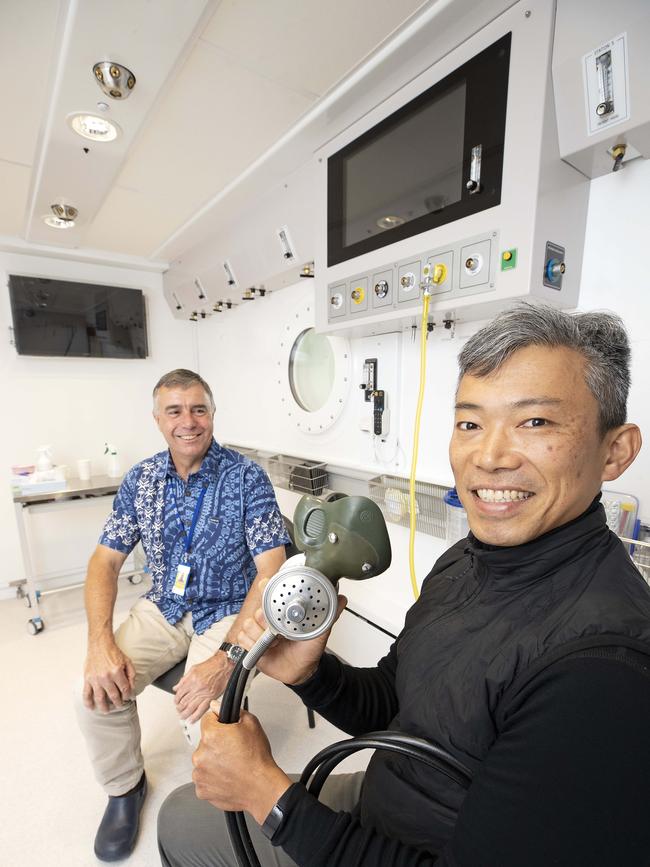

The Royal Hobart Hospital’s department of diving and hyperbaric medicine is one of the busiest of its kind in Australia.

Darren Meehan, staff specialist in diving medicine, said the department treated between 25 to 30 divers a year – both recreational and commercial – for decompression illnesses.

Divers are brought to Hobart for hyperbaric treatment no matter where they are in the state, with the facility open 24 hours, seven days a week.

Because of their injuries, Dr Meehan explained it could be dangerous to airlift people with decompression illnesses – so helicopters have to travel at very low altitudes, below 1000 feet.

He said if someone became ill in a mountainous region, like Strahan, the northwest or near Elephant Pass, it might be better to transport them by road.

“When we treat a person with ‘the bends’, what has happened is that person has been diving for a period of time on compressed air and they’ve absorbed a large amount of nitrogen and that’s in their tissue,” Dr Meehan said.

“When they start to ascend, that bubbles into a solution and goes into the wrong place where you can’t get rid of it.”

He said divers could come to the surface with symptoms either mild or severe, like aches, pains, tingling and rashes.

In more serious cases, divers can suffer a serious, even fatal condition known as a cerebral arterial gas embolism (CAGE).

Dr Meehan said when divers suffered from CAGE, they might come to the surface unconscious, or suffer neurological or central nervous system symptoms like confusion, loss of balance, and changes in hearing and vision.

“That can be a concern that we’ve got air in the brain,” he said.

Embolisms can also overwhelm the lungs in certain cases, or even the heart – particularly for the one in four people who have what is commonly referred to as a “hole in the heart”.

The chamber of treatment

After arriving at the Royal Hobart Hospital, divers with decompression illness or CAGE will be taken into a room where they will be administered 100 per cent oxygen in a pressurised environment.

That’s compared to the 21 per cent oxygen that humans breathe while walking the earth’s surface.

A patient will sit in the chamber, accompanied by a nurse, wearing a hood delivering the oxygen.

Dr Meehan said the pressure in that room would start at the equivalent of about 18 metres underwater for the first two hours of oxygen treatment, with another two hours at nine metres, before “coming to the surface”.

“What we are doing there is we are crushing any bubbles that have come out of solution,” he said.

“We are giving the patient 100 per cent oxygen to give them plenty of oxygen to breathe, and to saturate their body with oxygen. It also provides a gradient for nitrogen to come out of solution and for them to breathe it out.”

He said the patient would receive a treatment a day until their symptoms had plateaued, plus an additional treatment, before they returned to diving.

Later on, and after they have stabilised, a patient can climb inside a “monoplace” capsuled unit alone for exactly the same treatment.

Get a check-up before plunging

Dr Meehan said the Royal Hobart Hospital was now working on a public awareness campaign, in order to get key safety messages through to Tasmania’s recreational diving community.

“Consensus among all my colleagues here at work is we are not frustrated, but more concerned that it is an unregulated industry. So you can go and buy scuba equipment or you can buy hookah equipment and you can jump in the water,” he said.

“Overall recreational diving is safe. But there are risks.

“We’re advocating that all divers, particularly people over the age of 45, should really get a regular GP check or come see a diving doctor for an assessment.”

Dr Meehan said all commercial divers were required by law to have an annual medical, and ideally recreational divers should too.

“Diving is not easy,” he said.

“That exertion underwater, and getting older – the cardiovascular risk increases.”

He said his team was also conducting outreach information sessions at popular locations like Bicheno, particularly working with local diving clubs.

A “dubious distinction”

David Smart is a Tasmanian diving expert, with thousands of hours of experience underwater, and is considered a world leader in diving medicine, having spent 35 years at the helm of the hyperbaric unit.

He said while only a small percentage of the recreational diving community in Tasmania could be considered “reckless”, he also noted that over the past four decades, the culture had changed “very little”.

Professor Smart said while some divers were highly motivated, competent and responsible, others were using unsafe hookah apparatus, even homemade equipment, with “great potential to kill them”.

“A horrifying statistic, per capita, is that Tasmania has about four times the national rate of diving deaths, and probably about 10 times the best (mainland) state,” he said.

“We’ve got the dubious distinction of being the diving death capital of Australia.”

He said it was possible Tasmanians participated in diving more than mainlanders, “because of the fact we can take seafood underwater, such as lobsters, abalone and scallops”.

“The situation from my point of view (is the culture) hasn’t changed, and there’s one white elephant sitting in amongst all of the issues – that recreational hookah diving is an increasing component of the risks and deaths occurring,” he said.

“The use of that apparatus has got me greatly concerned.”

The dangers of hookah

Professor Smart said over the years, he had tried to get the message out about safe hookah equipment, “but we haven’t made any inroads”.

“These are probably more likely to kill divers than any other apparatus,” he said.

“It’s an apparatus that supplies compressed air to divers underwater, and there is no legislation that mandates that recreational hookah divers have to have their equipment well-maintained or producing clean air.”

Professor Smart said the problems were compounded by the fact there weren’t any readily-available hookah diving courses – and many hookah divers hadn’t even done a basic scuba course.

“With hookah, basically someone pulls a lawnmower engine, which runs a pulley, which runs a pump and then the pump sucks in gas around the boat environment and pumps it down to the divers,” he said.

“In that system, there are a lot of areas where it can fail.”

He said lawnmower engines were notoriously unreliable, with an exhaust system that “pumps out dirty gas”.

“That can be pumped straight down to the divers, and kill the divers with carbon monoxide poisoning.”

Splitting air between multiple divers underwater in a hookah system could also prove dangerous, with the person with less pressure – higher up – “stealing” most of the oxygen.

“That can lead to the person down deeper being compromised and having to race to the surface, because they’ve run out of gas,” he said.

“If you race to the surface holding your breath, you can rupture your lungs, which can lead to a chest injury with gas everywhere, or you can get gas pumped up to the brain, with a gas embolism.”

Professor Smart said the same troubles could occur when hookah divers accidentally dropped large catches, sending them rocketing to the surface.

Underwater and under-regulated

Professor Smart noted there were currently no governing regulations, and no specific training, for using hookah equipment.

“It’s still possible for homemade systems to be rigged up with inappropriate air sources, such as paint compressors,” he said.

“The owner of the equipment is totally responsible for all the things that a dive shop would guarantee – that equipment is going to pump safe air down to the diver.”

He said the practice “falls between all the cracks” as it was not governed under occupational health and safety legislation in the same way as commercial diving, it wasn’t covered by the state’s boat safety body, Marine and Safety Tasmania (MAST), and divers would not be apprehended by police or Fishing Tasmania as long as catch limits were followed.

“If the police come to you for checking fisheries, you should (need) to demonstrate that you’re actually a qualified diver to them,” he said.

“(Whereas) if someone is using scuba gear, they have to show their dive ticket to get their dive tanks filled when they go to a reputable filling station. The hookah never has that sort of check.”

Professor Smart also recommended a mandated safety checklist when buying and selling hookah equipment, and that there be a blanket ban on second-hand hookah gear.

“It can be second-hand, third-hand, fourth-hand, fifth-hand. By the time it gets to the lower common denominator, it’s a death trap.”

Risk versus reward

Passionate Tasmanian scuba diver Ken Saville has enjoyed some of the best moments of his life underwater.

The president of Launceston’s Ocean Divers Plus Scuba Club has dived with whales, dolphins and penguins, swam among underwater kelp forests and caves, and witnessed some of the most beautiful sights of his life – such as the underwater beauty at the mouth of the Tamar River.

But he’s also aware of the dangers, which he says can turn fatal in just moments.

“It’s a risky sport. Like everything, you’ve got to respect what you’re doing, otherwise things can go wrong very quickly,” he said.

On one occasion, Mr Saville lost his vision through a carbon dioxide “hit” caused by overexertion at 38 metres deep against a strong current near Bicheno.

“Your body starts shutting down and the first thing to shut down is your vision,” he said.

However luckily, he had a blurter – an underwater horn – that alerted his diving “buddy” that something was wrong.

On another instance, he was run over by a ship in the Tamar River.

Mr Saville recommended always diving with a friend – one who “knows you and knows your gear” – and for divers to dive within their capabilities.

He also recommended divers not try to lift large catches up through the water column, but use a buoy instead.

Mr Saville said going down too deep could cause a condition called “narcosis”, where the effects of nitrogen could “make you drunk underwater”.

He said adding more oxygen to scuba tanks could help reduce its effects.

“Rules, they’re there for a reason – but the main thing I’d say is knowledge,” he said.

“When you do enough courses and learn about the things you can and can’t do, you respect it a bit more.

“You’ve got to be really careful, and not do stupid things.”

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

‘No bias’: Planning Commission boss on Mac Point stadium

The fall out over a draft assessment of the controversial Macquarie Point stadium continues. Read the latest in the ongoing saga.

‘Left to rot’: Hunters slam aerial deer cull program

Hunters call for cheaper, more sustainable solutions to the deer population problem as the aerial culling program begins in Tasmania’s central plateau.