Henry France loved watching the Boxing Day Test cricket. And most other sports too.

He loved all things Christmas, and planned and bought his gifts months in advance. He loved the television show Friends, his family, his french bulldog-chihuahua cross Yuki, doing his own washing and working at Maccas to save money to buy expensive trainers and technology.

He was loyal, funny, kind, generous, an endless source of laughs and energy, and the “frontman” in social situations for his younger brother Zac.

He was a “jack of all trades and a master of none”, loving all sports and throwing himself into a variety of them including cricket, tennis, basketball, rugby union, soccer and gridiron.

His “loud enthusiasm for life” was undeniable, though sometimes it got him into trouble. If he was angry, he didn’t stay that way for long and was always the first to say sorry.

He would often jump into bed of a morning with his mum to talk about her day’s agenda, discussing the latest twists and turns in politics.

At age 18, less than a month before finishing year 12, after having a cold that didn’t go away, Henry France, a strapping, sport-loving, 190cm-tall lad, was diagnosed with leukaemia.

After expecting a cure, after doing everything he was asked to endure, after experiencing the full gamut of emotions from disbelief to frustration to anger, after spending 14 of his last 18 months in hospital undergoing gruelling treatments including chemotherapy, radiation and a bone-marrow transplant, after bone and blood infections and seizures and other endless complications, Henry, 19, succumbed to the disease in February last year.

His death has left a gaping hole in the France family that will never heal.

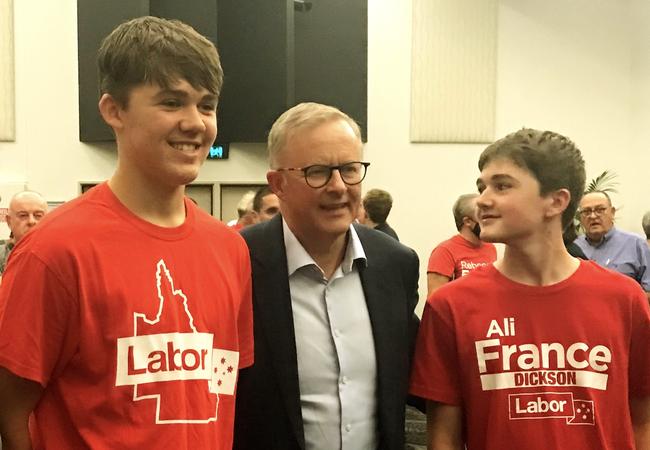

Henry’s mother, Ali France, is no stranger to adversity. A former journalist and communications manager, and now the Australian Labor Party candidate against Opposition Leader Peter Dutton in the seat of Dickson in Brisbane’s outer north, France, 51, came within a whisker of losing her life and that of her son, Zac, in a horrific 2011 accident in which she was pinned between two cars in a suburban Brisbane shopping centre car park.

Zac, then four, was in a stroller that was dragged under the car. Incredibly, he escaped with only deep burns to his leg.

The incident resulted in permanent physical injuries to France, whose femoral artery was severed and her left leg amputated above the knee in a dramatic, emergency operation that was performed without time for anaesthetic to be administered. Doctors later told her she was as close to death as a person could be.

She endured years of operations, infections, failed prosthetics, relentless, intense “phantom pain” in the leg she no longer has, and a surgical procedure called osseointegration in which a titanium rod that connects to a prosthetic was permanently implanted into her femur.

The 2011 incident also left France with deep mental scars, suffering years of post traumatic stress disorder over the experience of almost losing a child, replaying over and over the scene of staring into the eyes of the elderly driver who was pinning her with his car. In a “frozen” state, the man’s foot was pressed on the car’s accelerator, the engine revving and smoke pouring from spinning tyres. All the while, France was screaming for Zac.

The fear of losing one of her sons has never left her and, tragically, Henry’s death has seen this fear realised.

Speaking from her home at suburban Arana Hills, in Brisbane’s northwest, France says Henry’s death is “a constant hurt”.

“My worst nightmare has now actually eventuated, I’ve lost a child,” France says. “Every day is another day away from when I last saw him and hugged him and that’s just so hard.

“I don’t actually see that getting better. I think as time goes on, it gets worse. It doesn’t compare to anything else I’ve been through.

“There’s a fear that some memories will fade. It’s a terrible, really terrible fear that the further away you get from having seen him, the further you get from having that real maternal closeness with him.”

In 2019, France was divorced from her husband and father of her sons, Clive France.

In an added hardship for the family, Clive battled a rare cancer, a sarcoma that began on his leg, and he died in September 2023 aged 54, just months before Henry passed away.

“Zac has lost his father and brother within six months,” France says. “Clive just adored the boys and they adored him.

“We got the call that Clive didn’t have long and Henry was himself exceptionally ill at the time.

“Henry couldn’t walk, he couldn’t move. The hospital arranged a special ambulance to take him to his dad. Clive did hang on for a few more weeks and Henry was able to go in a wheelchair and visit his dad more times in hospital. It was all just terrible.

“It breaks my heart for Zac that it is just the two of us now. There’s no Clive, there’s no Henry.

“Zac has always had Henry at the front. Henry was always comfortable in an adult’s environment, always comfortable chatting to people. It’s hard for Zac without his brother in group situations where Henry would have been the ice-breaker.

“Henry was the person who gets everyone together. In many ways, as the younger brother, Zac followed Henry’s lead a lot.”

In September 2022, France took Henry tothe doctor because he kept getting sick. He had a persistent cold he couldn’t seem to shake, as well as some dizzy spells.

France was told an initial blood test showed nothing out of the ordinary but she took him back to the doctor again a couple of weeks later when he was still no better. A different doctor re-examined his previous blood work and ordered another blood test.

By that evening, Henry was admitted to hospital. The next day he underwent a bone marrow test and about a week after that began chemotherapy.

And just like that, Henry’s teenage plans of going to Schoolies, getting his driver’s licence and starting his Bachelor of Justice and Criminology degree at Griffith University were put on hold.

“He was so angry, it was so unfair,’’ France says. “He wasn’t able to celebrate finishing grade 12 properly and it was hard on an 18-year-old who had to be isolated when his immune system was very low.”

In May 2023, Zac, now 18, was the donor for Henry’s bone marrow transplant. It was an imperfect match but the best option after an exact match couldn’t be found.

France says Henry faced many complications during his treatment including anaphylaxis from chemotherapy, seizures, losing function in his arm, paralysis in his eye, and numerous bone and blood infections.

“When Henry was first diagnosed, we were told he would be cured,” France says.

“But everything that could possibly go wrong, did go wrong.

“He had a lot of really unusual reactions to the transplant and was in hospital afterwards a lot longer than expected.

“The amount of medications he had to take every day was like a full-time management job, it was massive. He had to be on steroids and his body completely changed which he really struggled with.

“In his last 18 months, he just grew up so quickly. He became so philosophical about things and very mature. He told me he loved me all the time. And he’d say things like, ‘Mum, you can only look after me if you look after yourself’.”

A week before Christmas 2023, Henry’s regular blood test was stable. He was using a wheelchair but was desperate to be out of hospital and the family spent a week at Noosa on the Sunshine Coast.

But a blood test on their return showed Henry had relapsed.

France says Henry reacted with anger.

“About a month before he passed, he ran away,” France says. “I mean he couldn’t physically run, but I finally found him in the hospital car park, next to the car just crying and crying, saying, ‘I don’t want to go back in there, I can’t cope with it anymore’. I took him home so he could just be at home for a night and I finally convinced him to go back to the hospital. It was terrible.”

France says she never contemplated her son wouldn’t recover. Even at this stage, he was given a new treatment option but, ultimately, he was too sick to begin it.

“The final week before he died, he had a final lumbar puncture and it showed 98 per cent leukaemia in his bone marrow,” France says. “It just ravaged him.”

The loss of Henry has left France reelingbut it also has compelled her to keep fighting politically, channelling her grief into hard work and “something purposeful”.

As the daughter of Peter Lawlor, a former Labor state tourism and fair trading minister, France grew up with politics. She dipped her own toes into politics in 2016 as a member of Labor Enabled, an association of the Labor Party for people with disabilities to influence and formulate policy, before standing as ALP candidate for Dickson in 2019.

France has been criticised on social media for talking about the loss of Henry – a “disgrace” as someone puts it – to use her grief and circumstance as an attempt to win votes.

Others have been more sympathetic to the family tragedy but question what it all has to do with politics.

And while France says she has “stopped caring” about the online vitriol, she does not apologise for talking about Henry.

“Politics is personal, actually,” she says.

“My whole life is the reason I got into politics. I will never stop talking about him and I don’t care whether it causes people to feel discomfort.

“There’s just never going to be a time where I’m not going to talk about him. I think about him non-stop. I still wake up some days and think he’s still here.

“It doesn’t mean I’m not able to work hard and throw myself into other things.”

Hard work is precisely what France thrives upon and says she is “hardwired” to try and fail, and try again.

“I’m not saying there is a way to get through this grief, I don’t know that there is,” she says.

“But I do know that I’m happiest when I’m working and being productive and being useful. That’s what I know about me and how I get through things.”

France has previously channelled her focus into sport as a way to distract herself from the constant pain she endured following her leg amputation and to wean herself off a “truckload” of pain medication.

As a novice, France joined the Sunshine Coast’s Mooloolaba Outrigger Canoe Club and in 2016 became a world champion para-athlete in the sport, representing Australia and winning two team gold medals and a silver. She also placed third in a solo sprint event and competed in a team marathon event in Tahiti.

France still takes no pain medication, though continues to suffer bad phantom pain in her missing left leg, as well as osteoarthritis in her hips, lower back and right knee – an expected trajectory for above-knee amputees. She will eventually need knee and hip replacements.

“I still have pain, it never leaves, but I’ve become an expert at managing it,” she says.

“And since Henry got sick, I’ve just stopped caring about it.

“I don’t want to ever be pitied or seen as a victim. I’ve just survived the best I can and these experiences will make me a better politician, if I’m elected. I’m obviously a different type of candidate and what you see in public is what you see at home. There’s no performance.

“I can advocate for people with a disability, and for people in the health system through my own experiences.

“I hope others who have been through similar experiences read my story and see that I have got through and I am getting through it. It’s so tough, you won’t get your old life back but you’ll find a new path.”

And so France is committed to running as the candidate for Dickson in this year’s federal election, in what is the most marginal federal electorate in Queensland.

It will be her third attempt at unseating incumbent Dutton in the electorate he has held for 23 years.

And she knows she has Henry’s blessing.

After his last relapse, and only six weeks before his death, France decided she would put a hold on her political career, believing Henry was facing another gruelling year or two of treatment, and committed instead to being by his side.

But Henry was having none of it.

“It wasn’t even a hard decision for me,” France says.

“I needed to be with him every day. But he was furious with me. He said, ‘You can’t do that, you’ve put so much into this, I want you to run, I want to see you up there.’

“It actually makes me feel good running as a candidate because I know this is what he would want.

“Doing the things we talked about makes me feel good. It’s turning that grief and struggle and tragedy into something purposeful and positive.

“And I know that it is something my two boys would be proud of.”

France has made it through her first, difficult Christmas without Henry, who loved the festive season so much.

Favourite memories of him span a lifetime – his “no off-switch”, giving-everything-a-go childhood; punching the air and holding his helmet up to a crowd of cheering parents after scoring 50 runs for Valleys (District Cricket Club) “like he was playing Test cricket for Australia”; watching his maths confidence blossom after working on algebra equations with him during Covid lockdown; conversations around winter campfires while camping at Somerset Dam; watching his last Ashes Test together in hospital and loudly yelling at the television at the suspense and drama.

But perhaps most precious of all, two weeks before he passed away, on a home pass from hospital, Henry asked to sleep in France’s bed with her.

“I just got to look at him like I did when he was a baby,” France says. “I just lay there staring at him for hours, watching him breathing like I did when he was a baby.

“I felt so grateful to have him, I had no idea he wouldn’t be with us two weeks later.

“He was so brave in his journey but he still needed his mum. It’s just a really precious memory and I’m glad I had that moment.”

France is tortured by her son’s final weeks and days, ruminating over what could have been done differently.

Ultimately, she lands in the same place: if the medical profession could have saved Henry, he would have been saved; if love could have saved him, he would have been saved.

“I’m satisfied that there was absolutely nothing more I could have done,” she says.

“There was absolutely nothing more the medical profession could have done. He couldn’t have been more loved and cared for.”

France remembers Henry in all the ways she can. She surrounds herself with his photos, his bedroom remains the same as he left it, she sometimes sleeps in his bed.

On August 20, on what would have been Henry’s 20th birthday, France got a small tattoo of his signed initials, copied from his learner’s permit, on her wrist as another small piece of him, a touchpoint her fingers often find.

She is grateful for the 19 years she had with the boy she calls “pure sunshine”.

She loved, and loves him immensely.

And that is something that will never fade.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Muso sets sights on Glastonbury in bold three-year plan

After leaving music behind, a Sunshine Coast engineer is making a bold return and setting out on a three-year journey to play 100 gigs with hopes to perform at a musical mecca in 2027. See what he’s promising some loyal fans.

Calling all mums and dads: Take the Great Parent Survey 2025

From school standards to screen time, we’re taking the pulse of Australia’s mums and dads – while famous parents like Olympic champion Libby Trickett are also diving in.