Wooley: Long, winding road to honour final wishes

Although I’ve yet to fulfill my parents’ final wish – to scatter their ashes at our ancestral home in Scotland – it remains on my to-do list, writes Charles Wooley

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

For too long I have deferred my responsibility as custodian of family history. When parents die the next generation should step up. But it is always a melancholy business. Hundreds of books, personal documents, military medals, old swords and telescopes, model ships, paintings and even a couple of mouldy old ancient Greek vases. All the miscellaneous memorabilia which beyond mere sentimentality means little enough to me and probably less to my children.

You can’t keep it forever but what to cherish and what to chuck? I should retain those volumes of yellowing memories invested in more than a century of photo albums, once lovingly curated, now stowed in an ancestor’s dusty sea chest and ignored by present generations.

I should also recognise there are my parent’s ashes waiting to be returned to a particular cascading stream which tumbles down a steep heathered hillside to gather and slowly meander among red-berried Rowan trees, through the glen down to a sunless sea, on the beautiful and misty Scottish Hebridean Isle of Arran.

I have yet to carry out that last parental instruction to spread their ashes in those shining highland waters of the celebrated Rosa Burn.

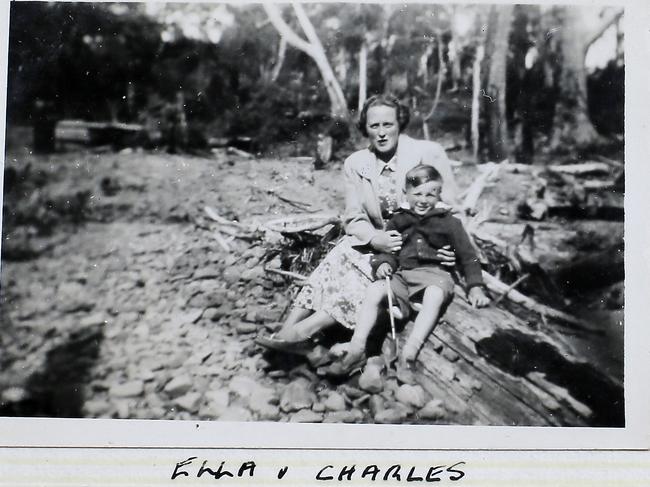

I was wandering the bush recently near Tarraleah in the Tasmanian highlands, taking a walk that my old mum Ella loved, a ferny track among tall timber and imposing man ferns.

As she often does, she stopped me with a word in my ear.

“What have you done with our ashes, son?”

I didn’t tell her that I had fleetingly considered decanting their mortal dust into the canal which feeds the vertiginous silver pipelines charging hundreds of metres down a mighty chasm into the Tarraleah power station which old Charlie ran. The ashes might go through his turbines and down the tossing white waters of the Nive to eventually roll with the Derwent into the Southern Ocean. In time, taking them all the way back to Scotland.

But no, I didn’t share that thought.

But I cannot be alone with this predicament. Substantially we are an immigrant nation. Since World War II more than seven million migrants have settled in Australia.

And a century before there was the Scottish and Irish diaspora which has resulted in an estimated more than a hundred million descendants living in America, Canada and Australia.

Among the old folks of more recent arrival the Scots and the Irish remain most prone to the postmortem romantic call of home.

And the burden usually falls on their ageing children.

“What have you done with our ashes?”

Her haunting ghost might make a book but unfortunately “Ella’s Ashes” sounds too much like an already occupied literary property.

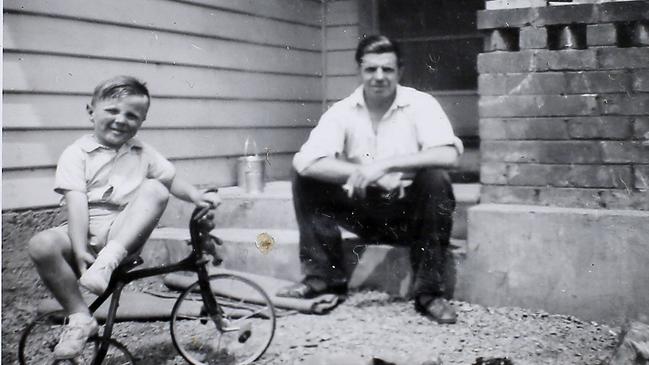

My practical father never makes such appearances nor any demands. On his side I come from a long line of seafarers from the wild western coast of Scotland.

Across each generation they were all named Charles, I suspect in honour of the “Bonnie Prince”. My family were MacGregors, and they fought on the losing side against the English in the 1745 uprising which ended in a calamitous defeat at a grim place called Culloden Moor.

Prince Charlie hotfooted it off to France leaving my clan to face his defeat. They had to change their name when the Crown outlawed the MacGregors along with their tartan. They were liable to be killed on sight for bearing either. They forfeited their lands, and some became wandering cattle duffers, a handy skill they brought to the early Australian colony.

Others went to America, taking with them a hatred of the English which was eventually put to good use during the American War of Independence. And some, like my family, turned to seafaring. They became fishermen and merchant seamen, even serving in the British navy.

That might seem oddly contradictory given how the English slaughtered and persecuted the highland Scots during what was called the “Highland Clearances”. But my old grandfather, another Charlie, once told me. “The fact is son, there would be no British navy without Scottish engineers. We invented the steam engine, and we ran every engine room in the fleet.”

He was born in New Zealand and was a young crewman aboard a troop transport that landed men at Gallipoli. “Lucky for you I was a sailor and not a soldier or you wouldn’t be here,” he would tell me. “We sent those young men off in small boats into a hail of bullets to die. It was a terrible massacre.”

Of course, my grandfather blamed the English. “The Auld Enemy” he called them.

His father was Captain Charles Wooley who also served the crown in Fiji as harbour master at Suva. My branch of the family were known as the “Fiji Wooleys” for their romantic and footloose love of what seemed like exotic travel. But today even the family stay-at-homes in Sydney and Auckland keep their ancestry close. Long dispossessed Scots seem to never let go.

It was certainly strange for me, growing up in Tasmania with people who sometimes seemed from another planet.

They got together with other Scots and Irish and played the strange rollicking music of the Gaels on an imposing highly polished mahogany radiogram. I preferred the Rolling Stones.

Ella would often tell me about the Battle of Culloden, which apparently was the existential reason we were in Australia.

I often challenged what seemed like an ancient fixation, “Gee mum, 1745 was such a long time ago,” and I was always told, “Son, it was only yesterday.”

My daughter Rosie once accompanied me on a work trip to the old country. We visited the ancestral Isle of Arran where, leaning on an ancient moss-covered stone humpback bridge she looked like she had never left the place. Rosie is a second generation Australian of Scots and Irish descent who had never been to Scotland. Yet she told me, “I have the strangest feeling that I really belong here.”

I’m going to give her Ella’s ashes.

Charles Wooley is a Tasmanian-based journalist