The day the ‘Field mouse’ took down the mob

Political advisers have created a network of expertise and techniques for manipulating information and we are all the worse off because of it, writes SIMON BEVILACQUA.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

MORE than 30 years ago protesters circled the government offices in Devonport.

Hundreds of people, many with placards, had heard Labor premier of the day Michael Field was visiting the North-West city and wanted to let him know how they felt about his plan to restructure education, as recommended in a report by Sydney management consultants Cresap.

The boisterous crowd was chanting anti-government slogans and banging with their fists on the doors and windows of the offices, demanding Field come out to address them.

They discovered the doors were actually open and began pouring into the small office. About 60 crammed in the waiting area, with many more pushing to get inside.

No matter the rights and wrongs of a protest, I always feel uneasy with mobs. The adrenalin of a densely packed gathering incites a volatile feedback loop of fervour that leads to otherwise normal people wanting to break things.

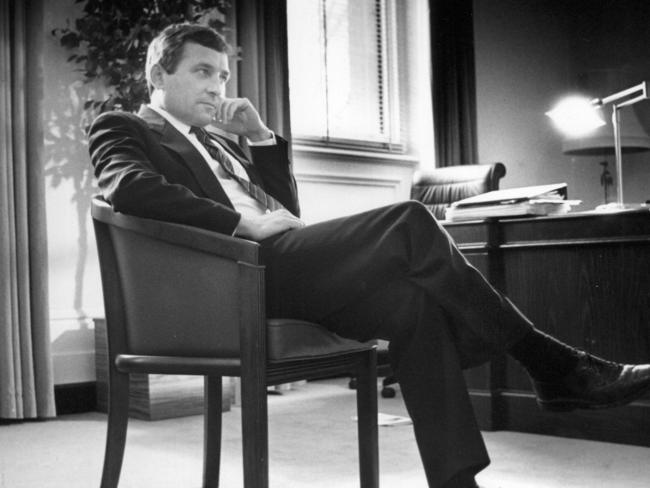

I was pushed against a wall, feeling claustrophobic, when a door near me opened, someone put their hand on my shoulder to usher me aside, and a short man in a suit forced his way to the middle of the throng.

Deep in the thick of the mob, he found something to stand on that lifted him to the average height of those around him and began to yell “oy”, like a farmer berating his sheepdogs for barking at a possum in a tree.

The farmyard tone worked, and the room hushed. A stage whisper circulated urgently from person to person: “It’s Michael Field.”

Field launched a spirited defence of his education reforms, explaining that the budget he had inherited from the previous Robin Gray-led Liberal government was a mess, and that restructuring would enable the department to survive until the state coffers were in a better shape.

Field had the mob in the palm of his hand — hanging on his every word. He had disarmed them with his surprise off-the-cuff oratory and its compelling delivery.

It was inspiring as he cast his gaze around the room, making eye contact and savouring each prolonged moment of silence that he used as dramatic pauses.

Then, just as the mob appeared to have been won over, a lone voice timidly called, “save our schools”, and again, “save our schools”, and by the third repeat, three or four others had joined him, and by six or seven the mob was in full chorus.

Field retreated into his office and the crowd spilled outside to wave placards.

A little while later, Field and I gazed at the protesters from his office window. I pointed out a placard that read “Field is a wimp” and told the premier the mob was chanting the phrase earlier. He chuckled at the puerile taunt, making an aside about the state of our democracy, and turned his back on the crowd to walk away from the window.

“I’m not a wimp,” he said, with defiance, and no longer laughing. “You can say what you like about me, but I’m not a wimp. I’ve faced more hostile crowds than any politician in Tasmanian history.”

It was a big call, but he was right. Few have faced anger like Field after daring to govern with the Greens in 1989.

Field’s performance that day in Devonport changed my view of him, and opened my eyes to the fact that commonly held perceptions of political leaders are often plain wrong.

Field’s opponents seized on his short stature, dubbing him the “Field mouse”, which came with the scurrying connotations of a rodent. He was treated as a turncoat, with the constant snipe that he was “in bed” with the Greens. He was portrayed as small, weak and timid.

But that memorable day in Devonport, I saw a brave man take on a riled-up mob with nothing but reason and walk away with a technical knockout. Field was not a wimp, as so many had chanted.

Nowadays, few reporters are able to get close enough to leaders to judge character. Advisers provide that kind of thing in back-room briefings and in tightly controlled photo opportunities.

I did not approach Field’s minders for an interview in Devonport that day, I just walked in off the street when everything was quiet and luckily found him alone.

Times have changed.

In 30 years, a weal of spin doctors (pardon my collective noun) has swollen up in the bureaucracy to stage-manage every word, every image.

In the late 1980s, the odd political journalist colleague would “cross to the dark side” to work as an adviser for an MP, but this escalated in the 2000s to the point so many reporters were recruited it became regarded as an inevitable career path for journos.

It became the norm for reporters fresh from university to spend a few years in as many roles in the media as possible, and then trade their $60,000 reporting gig for an $80,000-plus junior adviser role and a chance to climb the advisers’ ranks. For some, that was their ambition from the start. Their interest in reporting was just as a stepping stone, and it showed.

Over 30 years, reporters’ pay packets kept at best a half-step ahead of the consumer price index, as senior advisers’ pay rocketed. They are paid big bucks to create and protect an MP’s reputation, which can and does mean they have to try to stop journalists, like me, from finding out the truth.

But, worst of all, advisers have created a national network of expertise and sophisticated techniques at manipulating information.

The PR machine, most paid for by taxpayers, now spans everything from big business to lobbies, footy clubs and community groups — and there are vastly more advisers busy spinning the truth than journos trying to expose it.

Peter Gutwein is our new working-class hero

May 8

INTRODUCING our very own working-class hero, Premier Peter Gutwein.

And it is more than just the Premier’s groovy panther tattoo — as revealed when he rolled up his sleeve for his anti-COVID jab during the election campaign — that has established Mr Gutwein’s street cred among workers.

Mr Gutwein’s Liberals can now quite justifiably claim to be the workers’ party, such was the significance of their stunning performance at the May 1 state election.

The Liberals have won the support of an overwhelming majority of blue-collar workers in the state’s three most working-class electorates — Bass, Braddon and Lyons — at three consecutive elections over seven years.

It is unprecedented, historic territory for the Liberals and is yet more solid evidence of a political paradigm shift that is under way in Tasmania and which I wrote about two weeks out from election day in this column.

For 75 years as a party, the Liberals were only able to win enough support from working-class voters for one term in government at best, and that was quite often due to the support of independents who enabled the Liberals to form a coalition government.

Historically, over many generations, the working class would inevitably drift back to Labor at the next election.

Tasmania, you see, was a Labor state — this political reality helped define Labor’s reputation, down through generations of voters and countless elections, as the party of the workers.

The Liberals were seen as a party of capital, which looked after the interests of the ruling class, the bosses, the powerful and rich — and were epitomised by the generic smiling face of a wealthy Midland grazier.

However, the extraordinary performance by Mr Gutwein’s Liberals at the weekend, which came on top of former premier Will Hodgman’s outstanding results at the polls of 2014 and 2018, suggests very strongly the Liberals have stolen Labor’s historic mantle as the blue-collar party.

This trend, if part of a paradigm shift, could suggest a turning of the tables in years to come where the Liberals become the most common majority government and multiple-term government, and Labor is relegated to the occasional term in power, most often in coalition.

I believe this paradigm change may be upon us, only time will tell.

The only hope for Labor is to recognise the groundswell trend of the past three elections and dare to meet the underlying political paradigm change with an equally significant overhaul of its internal structures and update of its ideological foundations to better fit the 21st century.

Labor, as they say when an Aussie Rules footy team is floundering, needs to find its brand. It’s been dishing up game after game of indefinable dross. It must realign its policies with a strong, modern brand to which the Labor candidates themselves can first commit their hearts and minds, and then lead the Tasmanian community.

This rebranding job will take years of courageous leadership and a willingness to do the right thing, so as to firmly establish a newly minted 21st century Labor brand with its roots firmly in history, but its eyes trained on the future. A host of new challenges facing Tasmania and the world demands it.

A classic example of what not to do was clearly on display in Labor’s pokies policy.

Labor leader Rebecca White was thrown under a bus by the party’s backflip on her bold policy to ban the pokies from pubs and clubs and confine them to casinos, which was aimed at improving the lives of a small but significant number of working-class families ruined by gaming technology that addicts and destroys, mostly in traditional Labor strongholds.

The policy backflip sent a sad message to the public about what matters to Labor — the party had chosen power over people, cold cash over warm hearts, and in doing so had highlighted the party’s lack of principles and ticker.

These are harsh words but reflect accurately how many voters were left thinking.

The revelation that the backflip was recommended by a Labor committee that included former premier Paul Lennon — a paid lobbyist for pokies king, the Federal Group — added another layer of grime to an already ugly mess.

That Ms White was forced to concede in the first days of the campaign that she had signed a deal with the Australian Hotels Association, promising not to upset them again, was the last straw.

I reckon 80 per cent of those who voted for Kristie Johnston in Clark had the pokies in mind as they stood with their pencils in hand in the polling booth.

Labor’s cold, calculating pokies backflip, its arrogant majority government stand and its refusal to speak about the environment, despite loud public outcry against developing national parks, anger at fish farms and existential concerns about climate change, have left the party’s reputation in tatters.

Does Labor still stand for workers? Well, yes, as long as that’s OK after checking with the big end of town and consulting the unions and lobbies who represent those who own the hotels, rather than those whose bums are on the bar stools.

Labor is a mess — back-room deals and clandestine talks have distorted and debased the party’s policies for so long that few can remember what it really represents.

And judging from comments since the election by churlish Labor candidates, the historic extent of Gutwein’s achievement is being underrated and any consideration it is part of a broader paradigm shift that could plague Labor for decades is being ignored.

No state or federal government is ever elected to a third term without losing some support. Long-term governments always face voter disgruntlement. However, for the third election in a row the Liberals achieved roughly 50 per cent of the primary vote. It’s a tad down on last election, but a huge result.

What is more, the Liberals in 2018 benefited from an unprecedented multimillion-dollar pro-pokies campaign.

Gutwein’s performance — just as decisive and I would argue much more significant — was achieved without anywhere near that campaign support. That’s astonishing.

At this point in time, if he wins majority government this time around, the likelihood of Gutwein extending the Liberal record to a fourth term at the next state election is more probable than Labor pulling off an unprecedented landslide swing to win majority government — and, if a fourth term came about, history would dub Mr Gutwein the hero of the Tasmanian working class and the Liberals as the party of the worker, something inconceivable just 10 years ago.