There are around 1500 First World War cenotaphs and memorials in communities across Australia, you’ll find them in the cities, in villages on the coast, in far-flung outback towns - austere, reverential, classically-proportioned monuments made of granite, marble and sandstone, often with a central obelisk atop a simple, heavy plinth.

Every Anzac Day these stone sentinels become the focal point for the Dawn Service - a tradition that is unique to Australia and New Zealand - reminding us of those terrifying moments the original Anzacs experienced in the pre-dawn darkness of 25 April 1915, waiting for first blood-red line of dawn to crack the horizon as they rowed ashore to an unfamiliar Turkish beach.

Yet the true purpose of a local cenotaph is to illuminate the names inscribed on the monument’s honour roll - the names of boys and men who grew up in the district, heeding the call to volunteer to put their lives at risk and fight for Australia.

Each cenotaph tells a story - a record of who served in a time of crisis, who returned home - and who did not.

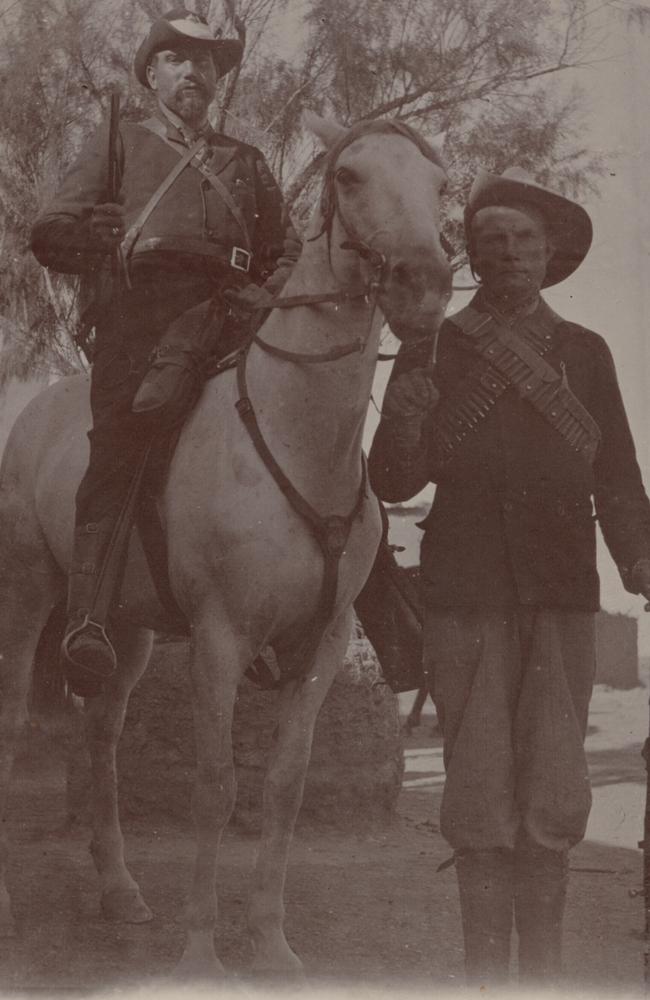

The polished stone memorial at Emu Plains on the western outskirts of Sydney is a prime example, in 1914 the pioneering settlement on the edge of the Hawkesbury River and the Blue Mountains was a simple, rural riverside farming community.

Yet when it was announced in August of that year Australia was at war with Germany, Emu Plains - like countless small country towns across Australia - had no shortage of eager men aged between 18 and 44 clamouring to volunteer for active service, indeed during WWI Australia with a population of under five million saw a staggering 416,000 men enlist.

It’s almost impossible to comprehend that in the space of four years some 60,000 young Australian servicemen would never return to Australia - killed on foreign battlefields - the grief and horror of such unprecedented death tore exponentially across Australia and plunged entire communities into mourning and incalculable grief.

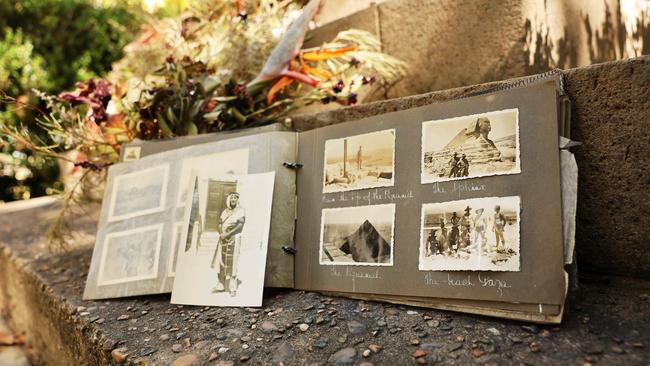

For the suffering families, relatives and friends there was no physical gravesite for where they could possibly grieve or express their sorrow - the remains of loved-ones killed in action were buried in cemeteries or lost forever in the countries where they fell.

To raise money for Emu Plains’ memorial, social days were regularly held where competitions such as Ladies Catching ‘Roos, horseback events, Ladies and Mens’ Throwing at Wicket generated important funds.

Paul Dukes’ family has been in the Emu Plains district since the settlement was founded in the early 1800s - Dukes Oval at which the memorial is located is named after his great-grandfather Percivalle Dukes who served in WW1 with his two brothers.

Percy returned from the war to become something of a local sporting hero, his brothers less fortunate - one killed in action and another surviving only a few years after the war ended before succumbing to what we would now call post-traumatic stress.

Paul is looking forward to the Anzac Day service held here at 11am, “It’s such an important day and it’s great to see families and kids attending - it keeps getting bigger and bigger.”

Wendy and Paul Cattell’s two great-uncles’ are both remembered, their names inscribed on the memorial - Reginald and Walter Cattell, both returned from The Great War, Reg even re-enlisting for WWII as a Gunner in the Royal Australian Artillery.

Indeed, the Cattell family were instrumental in organising the construction of the memorial a century ago, collating reports and helping to decide on the monument’s design.

Standing before the obelisk Wendy stresses to me the importance of what Anzac Day means to her, before her eyes well up and her voice falters.

“I’m sorry” she explains. “I just get very emotional about these things…”

Indeed some of the stories behind the names on the honour roll are heartbreaking.

Emu Plains carpenter George Clissold was considered old when he joined the Australian Army at age 42 in 1915.

He’d been married to his wife Mary for precisely 20 years and was renowned as a loving father to his son Charles and two daughters Mary and Bessie before making the decision to leave the farm and family at Emu Plains to do his bit for Australia - join up, give the Germans what for and see the world.

In a letter home from France young Charles described how he’d spent his 18th birthday “at the front in a very different atmosphere to that of the peaceful surroundings in Australia of my previous birthdays.”

In Flanders on 7 June 1917, the Australian 36th Battalion engaged in the Battle of Messines where 18 year-old Charles Clissold was killed on the same day.

Today, you can find the names of George and Charles Clissold - father and son, one above the other - on the Soldier’s Memorial at Dukes Oval, Emu Plains.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Why Minns is tackling WFH with carrot rather than a stick

The Minns government has now decided on a carrot instead of the stick approach in its long-running war on working from home.

Amy Shark lets far north haven go

ARIA Award-winning singer-songwriter Amy Shark and her husband and business manager Shane Billings have sold their retreat at Casuarina on the Tweed Coast.