The rise and rise of Northern Territory identity Mick Burns

Australia’s largest saltwater crocodile farmer is streetwise and shrewd, not unlike the prehistoric animal he farms

Northern Territory

Don't miss out on the headlines from Northern Territory. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Australia’s largest saltwater crocodile farmer is streetwise and shrewd, not unlike the prehistoric animal he farms.

A day in the life of Mick Burns starts with an early morning three-hour helicopter flight from a Bees Creek helipad that backs on to his main farm. Bees Creek is roughly 35km out of Darwin.

Our destination is the East Arnhem community of Ramingining where ‘Burnsy’ has spent the last three years putting in place a major community farming project.

If the trip to ‘Ramo’ is a long one, then the path to this moment for the former Territory cop has been longer and just as spectacular.

Our trip takes us into the deepest parts of Arnhem Land and the largest swamp in the southern hemisphere. Breathtakingly beautiful, Burnsy has an office to envy.

Michael John Burns was born in 1963. He has no formal education qualifications other than what he has learned on the streets and through the trial and error of business. Today he deals with the world’s famous fashion houses and mixes with the elite through the sport of kings — horseracing.

“As a bloke I can talk about crocodiles with a passion, anytime else I need a few drinks to get two words out of me,” the husky voice says through the thumping noise of the helicopter headphones. A 600-hour veteran, he bought the R66 Turbine to commute in. He waited for a strong Australian dollar before investing in this $1 million piece of equipment, symbolising his shrewd approach to acquisitions.

Burnsy has built his business empire over the last four decades. It started managing a pub at Daly River, progressing to a seafood wholesale business in Carey St. He then expanded into pubs and clubs operating at various times landmark hotels and turning them into the “it spot”. Each time he backed himself a bit further.

The pub scene drove him to shape the Mitchell St strip and a nightclub called Discovery. The single largest venue in the city, it stands as a monument to Burnsy’s investments.

He still keeps a finger on the hotel scene through Monsoons, The Tap Bar and The Cav, the original site of Darwin’s first legal casino.

To survive and thrive in the nightclub market you need to be fairly shrewd, not too unlike the saltwater crocodile.

“Crocodiles have a pretty small brain and have survived thousands of years, and you have to be pretty streetwise and cunning to do that,” Burnsy says with a touch of admiration.

In 2000, with Discovery up and running and his first Darwin Cup winner under his belt — Star Bullet, a gutsy grey owned with business partner Brooke David — he was asked to enter the crocodile industry.

The approach came from two of the Territory’s highest-profile businessmen — Leo Venturin and Neville Walker — to reinvigorate the flagging Darwin Crocodile Farm. Burns, with no history or understanding, was called in to turn it around.

“In those early days I had to do a lot of research and learning about the industry, so I went and talked to every stakeholder I could about the industry,” he says. “I talked to station owners, traditional owners, scientists, other industry people and fashion houses. I built relationships to strategically plan and build the business.”

In 2012 he took majority ownership with Porosus Pty Ltd, the entity which is his flagship.

The talk of crocodiles is an on-switch. Burns wants to be a world leader in best practice and this is what drives his approach.

“I don’t think anyone can really criticise the conservation outcomes of crocodiles in the Northern Territory,” he starts.

“It has been very good. One of the most successful conservation programs of any species anywhere in the world over the last 20 to 30 years.

“We rely on crocodile populations and we have a vested interest in crocodiles. We want to make sure that whole sustainable model has good crocodile populations in the wild — no question.”

Burns is pouring an enormous amount of money into animal welfare research to enhance the industry and spread the benefits. As we close in on Ramo he says the future of the industry is not guaranteed without this work.

“We are making sure we have got good WHS, good environmental concerns and good animal welfare. We are trying to farm smart — we’ve got vets, we’ve got good water people and we’ve got 11 institutions for research purposes,” he says.

“We are doing a lot of work understanding what stresses crocs and what doesn’t, so we are not sitting there speculating on whether the animals are happy or not. We are doing science-based tests.

“This research adds a lot to the sustainability of our industry. We are looking for a long-term industry.

“We have to have long-term relationships with the markets so they are relaxed that we are growing crocodiles with the right techniques, with the right science, supporting what we are doing. We have to continue to manage and monitor so it can be approved by CITES, signed off by the Federal Government and signed off by the Territory Government.”

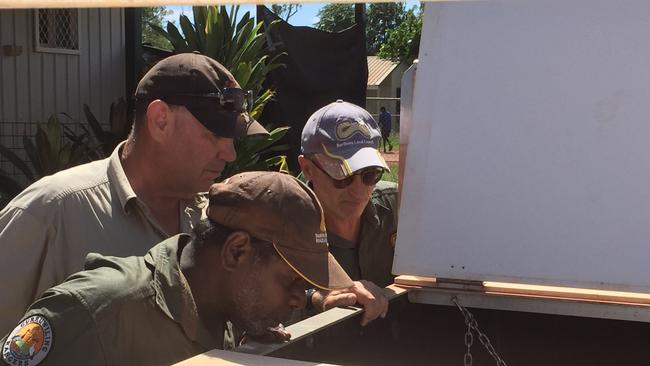

We land in Ramo after a quick stop to inspect hatchling pens in Maningrida and are met by his number one man, Otto Campion. The Ramo crew has already supplied two years’ worth of crocodile hatchlings.

“Otto is the boss out here,” Burns says. “He makes sure everyone is doing their job. Last year’s crocs were beauties.”

At 49, Otto is one of the local rangers who manages the homelands. Management includes water buffalo, mimosa and controlled burning. His experience has taught him how all the aspects of their land management is interlocked.

“We culled a lot of wild buffalo and we found that the following crocodile nesting season we had more nests,” he says. “The buffalo trample the nests or destroy the areas where they nest.”

The meat of the water buffalo is used to feed the hatchling crocs. Fire is also important.

“When we have an uncontrolled fire it takes away all the material crocodiles use to build nests, the same with mimosa,” Burns says.

This appreciation has meant a new realisation of the opportunities for farming crocodiles at Ramingining.

Otto takes us to the purpose-built hatchling pens.

Immediately Otto starts talking to the hatchlings, now 40cm in length, they respond by crowding around expecting food. He mimics the noise of a baby hatchling and they scamper more.

“We normally go and collect the eggs with the traditional owners and the ranger groups,” Burns explains. “We then buy the eggs from them and incubate them in Darwin. We put them into what we call hatchling pens and we grow them up and put them through the farming system. What we are doing at Ramingining is we’ve got some makeshift incubators and we’ve got some hatchling pens. We’ve been working on this project over five years now.

“The first two years we developed at the Croc Farm (Bees Creek) and it was all about the practicalities of water in, water out, about the practicalities of cleaning and what we did after that was we moved the two hatchling pens out to Ramingining and we actually farmed them two years ago.

“So the eggs go down December, January, February and sometimes March. The incubation period is about 90 days and it depends on temperature. Last year we upgraded the pens and the rangers at Ramingining produced absolutely cracking babies — the biggest one was about 97cm. There were 127 and almost no mortalities, and they averaged over 80cm.

“We buy them per centimetre as opposed to per animal. The farms actually guarantee to buy them, so that underwrites the risk factor. The community is growing the crocs and are able to sell them.”

Burns admits he can grow the crocs a lot cheaper than what he can buy them through this system, but his relationships developed over decades go well beyond the cost efficiency of this.

Also at Ramo is a consultant from the NT Government Department of Business. Burns asked the NT Government to stump up $400,000 to turn the two pens into 20, so they can turn out 2000 crocs and generate about $400,000 in revenue for the community.

The business model must have stacked up, because the NT Government announced the money in its Budget this week.

“We’ve been working together since 2002 out at Arafura Swamp and we have gradually started to get a closer and closer relationship ... we’ve got a very trusting relationship and we decided we’d start to explore the opportunity to start growing babies out here,” Burns says.

“The NLC has been working with us. It has got real ownership. The local people own it and operate and they get the funds from it.”

Otto sees plenty of ‘other’ potential in the system, including channelling the waste water from the daily cleaning of the hatchling pens to fresh produce fields. They have plans to grow mangoes, watermelons and bananas for local consumption, either selling the produce to ALPA, who operates the local store, or to others.

We leave Ramo for a quick fuel stop at Arafura Swamp. It is the main collection ground.

It is majestic; 700 sq km that expands to 1300 sq km by the end of the Wet.

In one strip Burns points out they found 20 nests. He also says a bushfire through the region may affect this year’s collection. It is a reminder of the fiscal nature of the environment and highlights the fact that the collection of crocodile eggs is guaranteeing the animal’s existence rather than diminishing it.

We refuel at an eco lodge on the edge of Arafura Swamp. I’ve just added it to my bucket list.

The flight home canvasses what we’ve seen in the day and we talk a bit more about horse racing, Aussie football and his daughter Arley.

“Mate, she’s the best thing ever. I love her dearly. And she has got me wrapped around her little finger,” a doting dad gushes. It is nothing like the former half back, who is now President of the Tiwi Bombers — another example of his association with indigenous communities that goes beyond business.

This association started during a discussion about croc collecting and a request from Cyril Kalippa Rioli, the father of the famous footballing family. The Bombers, who have started to combat youth suicide on the islands, are at a crossroads in their 10th year and Burns knows it is time for the community to retake ownership of the team.

His commitment to them goes beyond man hours and stretches into tens of thousands of dollars — none of which he wants credit for.

But before we can explore this further our conversation is interrupted by a waterfall and Burns tilts the chopper to give me a better view.

For more stories like this, subscribe to the NT News and other News Corp Australia metropolitan newspapers and websites, such as the Herald Sun, by visiting ntnews.com.au/subscribe.

Originally published as The rise and rise of Northern Territory identity Mick Burns