‘People are dying’: Suicide crisis in regional Aussie city

At just 21, she had the world at her feet. But Kitana’s tragic suicide, months after her “protector” brother took his life - has exposed an “alarming” crisis.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are warned that the following article contains images of deceased persons. Distressing content.

Community leaders in a regional Australian city say they are burying too many young people as “alarming levels” of trauma leads to a mental health and suicide crisis.

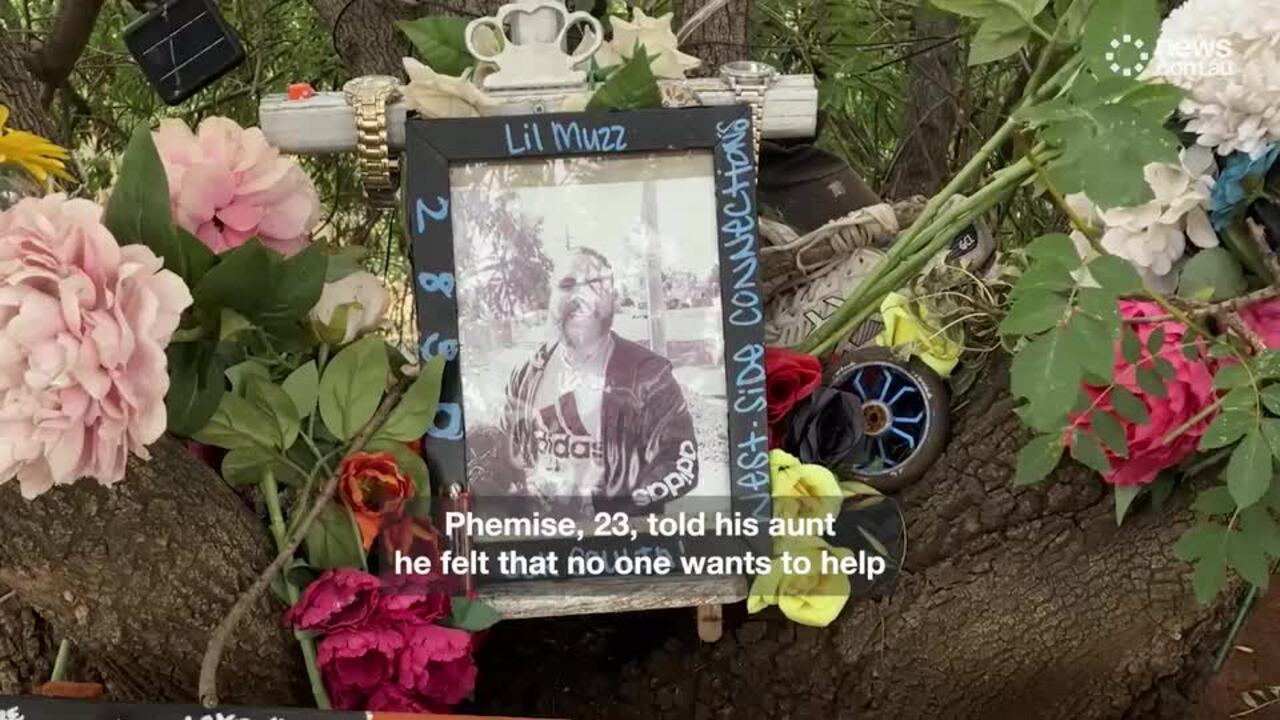

The deaths of siblings Phemise and Kitana Murray last year, both to suicide, highlighted the devastating reality of life in regional hubs like their hometown of Dubbo, NSW.

Family of the brother and sister, who were aged in their early 20s, say both had been let down by local services as they desperately tried to get help in their finals weeks and days.

Locals have told news.com.au too many young people were dying in the region, which has a significant Indigenous population.

Elder Riverbank Frank Doolan said mental illness and suicide has been a major issue for the area “over a sustained period of time”.

He said efforts to bring in services like Headspace amounted to “moving deck chairs on the Titanic” and a lack of access to housing and intensive treatment “has fatal outcomes for our young people”.

“What has happened is what I would call window dressing,” he said.

“It’s not giving these young people and our most vulnerable access to real psychologists in real time.

“That needs to be addressed and it needs to be addressed urgently.”

‘Help us stay alive’

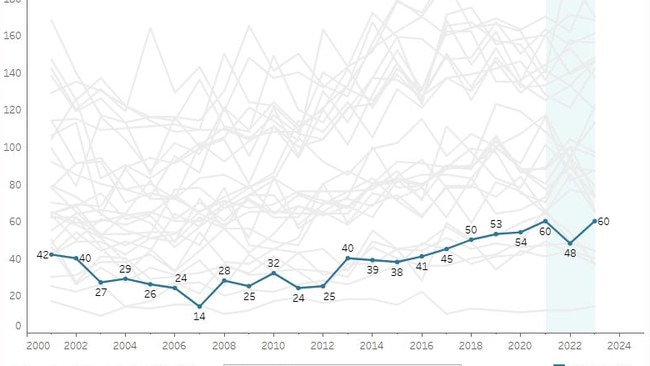

Data from the Australian Institute for Health and Welfare shows 65 people died by suicide in the Dubbo statistical area between 2019 and 2023. AIHW data also records 60 suicides in the Western NSW health district in 2023 alone.

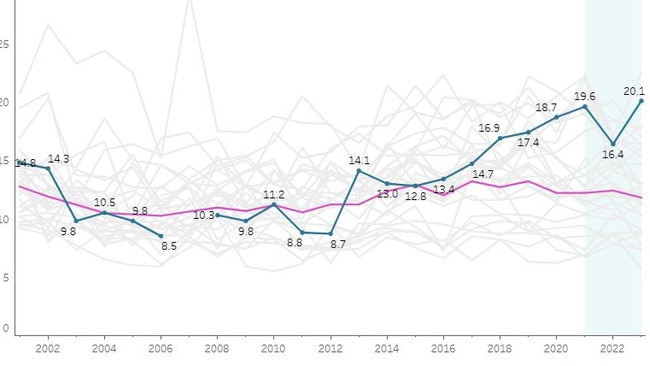

Suicide is the leading cause of death for young people aged 15 to 24 in Australia, and First Nations peoples are three times more likely to die that way than non-Indigenous citizens.

The region has a population of 75,188 people – 15.7 per cent of which are Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander - with the city of Dubbo itself having about 43,000 residents

Nationally, the rate of suicide among Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander population (29.9 per 100,000) is about two and a half times higher than it is for non-Indigenous peoples.

Uncle Frank said the trauma young people experienced in regional areas was “at alarming levels”, adding that mental health did not discriminate along racial lines.

He called on NSW Mental Health Minister Rose Jackson to visit the community: “Help us to help the young people stay alive”.

One Dubbo resident Stephen told news.com.au in the eight years his family had lived there, they knew 17 Aboriginal friends or neighbours who had killed themselves.

He believes there is a “culture” at Dubbo hospital that dismisses Aboriginal patients who go for help.

Another elder, who asked to speak anonymously, said the impact of intergenerational trauma was significant in isolated areas like Dubbo and the Western Plains.

Despite the funding being pumped into the sector, it was difficult to see any significant impact, they said: “We’re going backwards.

“We’re burying up to 30 young people every few months. There’s drugs and alcohol, there’s suicides.

“People are dying from alcohol abuse young. You can’t tell me that’s not mental health.

“It’s people numbing themselves.”

‘A lot of disadvantage’

Dubbo Mayor Josh Black has been highly critical of the NSW government’s decision last month to scrap plans for a $48 million indoor sport centre in the city.

Mr Black said it made “no sense” to cut the sports hub project, which would have included an expanded PCYC, gymnastics and basketball facilities.

The mayor said there was a youth crime problem in the district, and such facilities were crucial to providing positive pathways and role models.

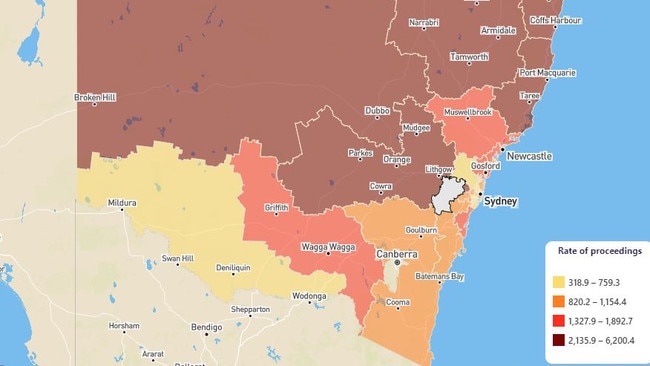

Data from the Bureau of Crime Statistocs and Research shows the number of youth offenders in the Far West and Orana area in the year to December 2023 was 726.

That figure came from a 10-17 population of 11709, and was more than double the rate of inner and southern Sydney - which has a higher population of young people.

“It just shows that in the Dubbo region there is a lot of disadvantage,” Mr Black said. “But one thing we really do need is investment in local programs that really make a difference.

“The state government needs to invest in diversion programs.

“We need a big investment into social programs to break the cycle of offending and reoffending so people don’t go down that path in the meantime.”

Tara Moriarty, the Minister for Regional and Western NSW, said in a press release in December the project was “no longer viable” following delays and cost blowouts.

The plans were first announced in 2018 by the former NSW Coalition government but works never began.

It’s estimated the proposal, which was to be wholly funded by the government, would now cost in the region of $70m.

Hospital in the spotlight

The treatment of Aboriginal people at Dubbo Hospital has recently come under scrutiny during a coronial inquest into the death of Kamilaroi-Dunghutti man Ricky Douglas Hampson in August 2021.

Mr Hampson had presented to the emergency ward complaining of feeling a pop inside his stomach, telling staff his pain was “10 out of 10”.

He told them he’d smoked cannabis earlier that morning and was misdiagnosed as suffering from Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome – characterised by nausea, abdominal pain and vomiting.

Hours later he was dead from the real cause of his agony, burst stomach ulcers that were left unnoticed and untreated for hours while he was under the hospital’s care.

A discharge summary was also wrongly sent to a Justice Health doctor at Wellington jail, despite Mr Hampson having been released from prison almost a year earlier.

Two experts told the inquest they were concerned Mr Hampson’s treatment had been influenced by “institutional racism”. The inquest heard the doctor’s CHS diagnosis was based “merely on him seeing Dougie being wheeled into” the hospital.

Deputy State Coroner Erin Kennedy accepted the doctor who misdiagnosed “Dougie” had a “cognitive bias that was created by his first impression”, but was not satisfied it was racial bias.

“I accept therefore as submitted that the part it did have to play was, on his own evidence, one of the reasons that (the doctor) reached his erroneous diagnosis was that he had seen plenty of Aboriginal people in the ED with CHS,” she wrote in her findings last year.

She referred the doctor who misdiagnosed Mr Hampson to the Health Care Complaints Commission and recommended a review of staff training and First Nations consultation in the local health district.

‘People are dying’

Former NRL player Joe Williams has become a campaigner for better mental health outcomes after struggling with suicidal ideation and bipolar throughout his life.

Mr Williams, who lives in Dubbo, said the city’s issues with mental illness and suicide had been “magnified” by recent events but stressed it was not new or an outlier.

Many communities across the country, particularly Aboriginal communities, faced the same struggle despite record funding and new services being rolled out.

“Yet people are dying more than they ever have,” Mr Williams said.

The Wiradjuri-Wolgalu man said it was time Australia was “brutally honest with ourselves” about why people aren’t accessing current services.

“There’s just too many services that just aren’t culturally safe.”

He said Aboriginal staff should be involved every step in the care of Aboriginal patients from presentation to follow ups.

He understands health staff are often “under the pump”, but said the story of the Murray siblings and death of Mr Hampson spoke of the problem his community was confronted with.

“These things keep coming up,” he said. “Where there’s smoke there’s fire.

“We need to be better because people are losing their lives.”

Western NSW Local Health District operates the largest rural mental health service in the state with acute services in Dubbo and Orange.

There are a range of mental health services available to Dubbo residents, including a suicide prevention outreach team and crisis centres.

“NSW Health recognises models of respectful, culturally safe and appropriate mental health care are critical for ensuring the best possible mental health and wellbeing outcomes for Aboriginal people,” a spokesperson said.

Ms Jackson said the state government had committed over $40 million over four years to Closing the Gap programs and Aboriginal mental health workforce development.

“We will continue to work towards reducing suicides in regional and rural locations and a vital part of that work is improving the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in NSW,” she said.

Mr Williams said $40 million was a lot of money, but said the suicide rates would continue to rise if fundings keeps going to the same places.

“Clearly if what they were doing in the first place was working, we wouldn’t be having this conversation,” he said.

“The same organisations get funded, the same programs fail to impact, the more people unfortunately we’re seeing losing their life - it needs to be better.”

Originally published as ‘People are dying’: Suicide crisis in regional Aussie city