‘Devastating’ proof Australia is broken, with the rise of the ‘working homeless’

The average income in Australia hit six figures this year, but new data reveals a job is no longer a safeguard against financial ruin.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Startling new data has revealed a “devastating” emerging trend from Australia’s continuing cost-of-living and housing crises, which experts say governments are failing to address.

It’s a scenario that shouldn’t be playing out, with inflation and rent rises easing in recent times and the average salary hitting a whopping six figures for the first time ever this year.

And on paper, Australia has the second-richest population in the world.

Despite that, the number of people who are gainfully employed but forced to access homelessness support rose in almost every state and territory in 2023-24.

“This is a humanitarian crisis and these shocking new figures must be a wake-up call for governments across Australia,” Homelessness Australia chief executive Kate Colvin said of the Institute of Health and Welfare’s annual report.

“We are failing people at every turn – more families, workers and older Australians are being pushed to breaking point by skyrocketing rents and a broken housing system.”

MORE: Half of renters experiencing financial difficulties

Across the board, rough sleeping and persistent homelessness has increased to “devastating levels”, Ms Colvin said.

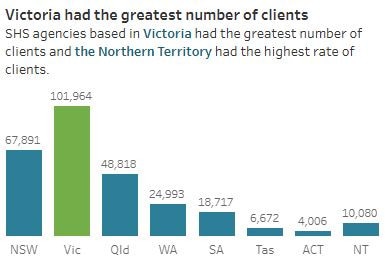

The latest data shows some 280,000 clients were supported by specialist homelessness agencies in the past year, up 33 per cent in two years.

But alarmingly, almost 35,000 people who needed emergency accommodation were turned away because there was none.

“We knew it was bad, but this data shows us it’s getting even worse,” Ms Colvin said.

A job is no longer a safeguard

The days when earning an income meant being able to put a roof over one’s head and food on the table are a thing of the past for a growing number of Australians.

At a national level, 23,794 working people sought help for homelessness in the last financial year, up 7.2 per cent on the previous 12 months and almost 27 per cent in the past five years.

The ‘working homeless’ trend is particularly dire in Victoria and Queensland – states that have seen particularly sharp increases in rent and home prices.

In Victoria, the latest data shows 10,105 people earning a wage were forced to reach out for help from homelessness services – up 9.4 per cent year-on-year and 20.8 per cent on 2019-20 figures.

The figures marked a record high and revealed an “alarming” trend, Deborah Di Natale, CEO of the Council to Homeless Persons, said.

“This sharp surge in the number of working Victorians forced to seek homelessness help shows the state desperately needs more ambition in tackling the housing crisis,” Ms Di Natale said.

“Having a job is no longer protection against homelessness, which is an alarming reality that we can only fix by investing in more public and community housing.”

MORE: Home loan trap taking years to escape

Meanwhile, in the Sunshine State, the number of working homeless hit 3494 in the last financial year, up 7.3 per cent on the previous 12 months and a staggering 48.2 per cent in five years.

New South Wales recorded a modest decrease, but 5704 people earning an income still sought help.

The number of employed people needing support in Western Australia grew by 8.3 per cent to 1887 in a year.

Increases across the board

The increase in ‘working homeless’ aside, broad demand for homelessness support has risen.

In too many cases, demand is so high and services are so stretched that the number of people turned away is also on the rise.

The state which saw the biggest increase in rough sleeping over the past two years was Queensland, with a shocking 51 per cent spike, followed by WA, with a 35 per cent jump, and Victoria, with an 18 per cent rise.

Today’s bleak data also reveals a rise in the number of people experiencing persistent homelessness as well as indications of a jump in the proportion of Aussies seeking help for the first time.

Across Australia in 2023-24, there was no housing support available for the 70 per cent of people who needed long-term accommodation support, Ms Colvin said.

That equates to 76,688 people asking for help but forced to fend for themselves.

It’s unsurprising, given finding an affordable home to rent has become a virtually impossible task, “grim” data from research firm PropTrack has revealed.

Housing costs hit home

Exploding demand for leased dwellings has collided with plummeting supply over recent years, seeing record growth in prices across much of the country.

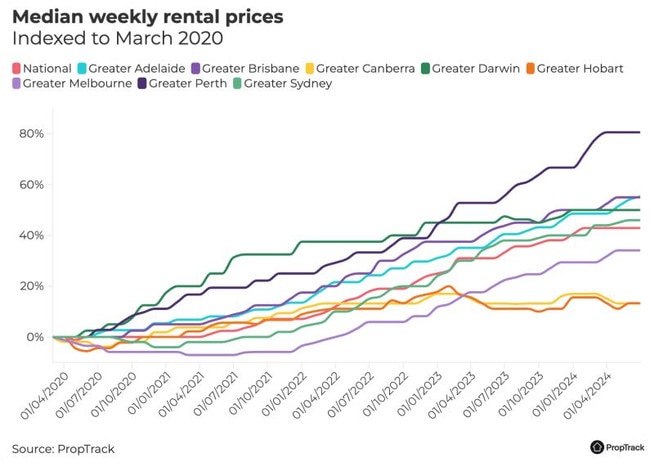

Karen Dellow, senior data analyst at PropTrack, said median weekly rents across all capital cities are “considerably higher” than they were at the start of the Covid pandemic almost five years ago.

As a result, the quest to find a rental that doesn’t break the bank has become tough.

“Nationally, the proportion of rental listings of $400 per week or less decreased from 43.1 per cent in March 2020 to just 9.3 per cent in October 2024,” Ms Dellow said.

“This represents a stark 78 per cent reduction compared with pre-pandemic levels and a 27 per cent year-on-year decline.”

In Victoria, the proportion of affordable rental properties across Greater Melbourne has collapsed by 28 per cent in the past year and 81 per cent since the onset of Covid.

In Greater Brisbane, the proportion of leased homes under $400 per week has evaporated by 16 per cent in a year and 84 per cent since the start of the pandemic.

And the Queensland Council of Social Services revealed in its latest Living Affordability Report that households are bleeding about 37 per cent of their income on keeping a roof over their heads.

The correlation between high housing costs and an increase in homelessness is clear.

Homelessness Australia said the number of people seeking help from support services as a direct result of housing affordability has leapt by 15.74 per cent in the past year.

Slowing growth a small comfort

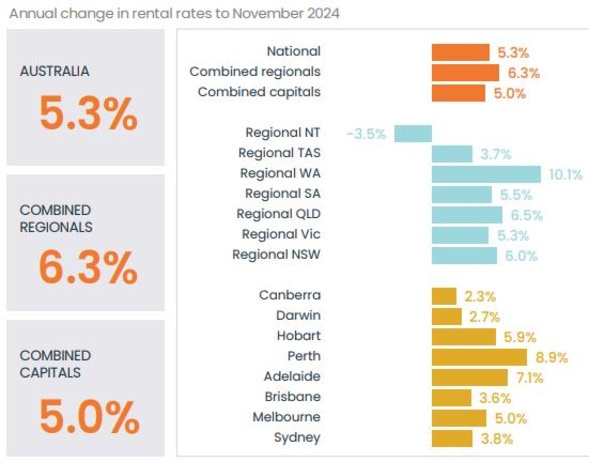

The latest data from research firm CoreLogic shows rent price growth continues to slow nationally, with the 5.3 per cent year-on-year increase in November the smallest since April 2021.

“Rental growth may rebound a little through the seasonally strong first quarter of 2025, but beyond any seasonality, it looks increasingly like the rental boom is over,” CoreLogic economist Kaytlin Ezzy said.

But prices are still painfully high.

SQM Research figures show the national average cost of renting a house is $707 per week, while for a unit it’s sitting at $618 per week.

And slowing growth aside, the extent to which prices have grown is eye-watering.

Over the past year, median rents have surged by 8.9 per cent in Perth, 7.1 per cent in Adelaide, five per cent in Melbourne, and 3.6 per cent in Brisbane, CoreLogic data shows.

That follows more than four years of sustained growth.

Those in the market to rent a home in major cities at the moment can expect to pay on average $833 per week in Sydney, $627 per week in Melbourne, $727 per week in Perth, and $661 per week in Brisbane, according to SQM Research.

More action needed

Homelessness Australia has called on governments to dramatically increase funding to tackle the “deepening emergency”.

“While the Federal Government’s increases to Rent Assistance and [its] social housing investment have made a difference, more must be done to address the crisis,” Ms Colvin said.

“We need an immediate injection of funding to stop the crisis from worsening. This is no longer a challenge for just the most vulnerable – working Australians and families are becoming homeless. Governments need to step up before the emergency spirals even further out of control.”

The group has called for governments to deliver an emergency funding package for homelessness services to prevent more Aussies from becoming homeless.

It also wants more funding for Housing First programs that stop people cycling in and out of homelessness, as well as an expansion of social housing stock, she said.

“The figures we are seeing today represent a failure of policy and lack of political will. It’s time for leaders to step up and ensure no one in Australia is left without the support they need to keep a roof over their head.”

Originally published as ‘Devastating’ proof Australia is broken, with the rise of the ‘working homeless’