Being stalked: How to know if it’s happening and how it leaves victims feeling confused

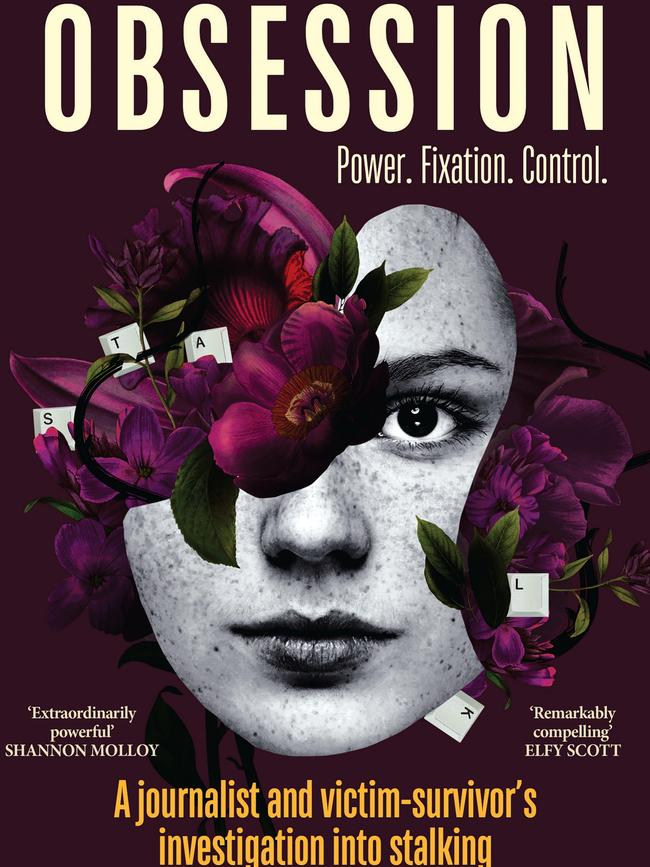

Stalkers are not limited to the reclusive or the delusional. In an extract from her book, Obsession, journalist and victim Nicole Madigan explains how to recognise if you are being stalked.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

I was around 14 years old when I found an envelope addressed to my mother in the letterbox of my childhood home. My eyes were drawn to the brightly coloured letters on the front – four in total, spelling out my mother’s name.

Reminiscent of a ransom note in an old-fashioned movie, each letter had been individually cut out of a magazine or newspaper and stuck to the envelope. Mum took a single folded sheet of paper out of the envelope and opened it. A slight frown, then a shadow of concern cast over her smiling face. I moved closer to her and peered over her shoulder.

Rose,

You are so beautiful.

XOXO

These words were also formed of individually cut-out letters. At the time, Mum was working

as a real estate agent, based at an office located around 10 minutes from our home.

About a week after receiving the letter, she received a phone call. The following week, another.

My parents called the police, which didn’t amount to much, and after a lengthy discussion, Mum decided to resign. Whoever had sent the letter and made the phone call knew what she looked like; they knew where she worked, even where she lived – and they wanted her to know about it.

When I look back on it now, it’s chilling; the sort of stalking scenario we might see play out in the movies. It was a totally different scenario from what I experienced years later – being harassed via text messages, DMs, and social media posts – yet both situations constituted stalking.

Much like the false narrative of the rapist being a monstrous stranger when the more likely scenario is that they are known to their victim, the deranged image most of us conjure up when we hear the word “stalker” amounts to little more than a caricature. We think of a man lurking in the bushes, watching in wait as his victim walks to her car. Or a stranger on the other end of the phone line, breathing heavily into the receiver. A friendless loner, a raging psychopath, a lunatic. Perhaps.

In reality, stalkers are not limited to the reclusive or the delusional. They are accountants and cleaners and dental nurses and teachers. They are fathers, mothers, grandparents. They are your neighbour, your colleague, your friend. And so are their victims. Quietly suffering, often unable to put a label on what’s happening to them. The range of behaviour is broad, their motivations are vast, and it’s happening right under our noses to an extraordinary number of people.

Accurately measuring how often stalking occurs is difficult. Reporting numbers are low; conviction rates even lower. Modern technology has made stalking rates even harder to quantify. Around 25 per cent of Australian women will experience stalking at some time during their lives, with around 8 per cent of Australian men impacted.

So, what is stalking?

Put simply, stalking is repeated unwanted communication or contact, in a way that would cause apprehension or fear in most people. The key word here is ‘repeated’. Stalking is less about the specific action, although behaviours are certainly an indicator of safety risk, and more about a pattern of behaviour. A single threat to harm another person, even a one-off physical attack, isn’t stalking.

This is where things get confusing, especially when it comes to the reporting process, says behavioural investigative Adviser Professor Cleo Brandt.

Demonstrating a pattern of behaviour, which is necessary to prove stalking, is difficult. As Brandt points out, ‘Even seemingly simple questions like “When did it start?”

can be difficult to answer. When exactly did the behaviour change from weird and annoying to frightening? What behaviours should be considered part of the stalking and reported to

police?’

Further complicating matters, she says, is the fact that most Australian police officers haven’t undertaken specific training around the nuances of stalking behaviour, and therefore don’t ask the questions required to ascertain that what has occurred is in fact stalking.

Identifying stalking is difficult enough, even when the actions are stereotypical of stalking, such as loitering outside someone’s home, incessant threatening phone calls or abusive messages. But when it comes to behaviours outside the stalking stereotype, the waters become even murkier. There lies a vast area of grey, where repeated unwanted actions that may seem inane to the outside observer create significant fear and distress in the target.

“That’s probably the reason why some people have such trouble recognising stalking,” says Brandt. “Because, as a stalker, the only thing that’s limiting you is your imagination.”

It’s this insidiousness that leaves so many victim-survivors unable to identify their own experience as stalking, let alone prove it. Despite the very real fear and anxiety, despite the mental anguish and paranoia, despite what, to them, may be incredibly clear and direct threats, they are still unable to properly define what is happening to them.

It took almost three years and an official police charge before I recognised what was happening to me as stalking. In the beginning, I believed it was something I could – and

should – handle myself. I thought ignoring it was the best approach, and while I was clearly wrong, the longer the stalking went on, the less I felt I could do anything about it.

In some cases, it’s nearly impossible to illustrate how particular behaviours constitute stalking outside of the context of the experience itself. It’s only after hearing others’ stories first-hand that I’m able to truly appreciate why certain behaviours instigate fear, and the extent of the short-term and long-term repercussions for victim-survivors.

Book pre-orders: Obsession, A journalist and victim-survivor’s investigation into stalking by Nicole Madigan | 9780645476712 | Booktopia

RSVP Sydney launch: Obsession Launch: Nicole Madigan in-conversation | Better Read Events

RSVP Brisbane launch: Nicole Madigan - Obsession (avidreader.com.au)

More Coverage

Originally published as Being stalked: How to know if it’s happening and how it leaves victims feeling confused