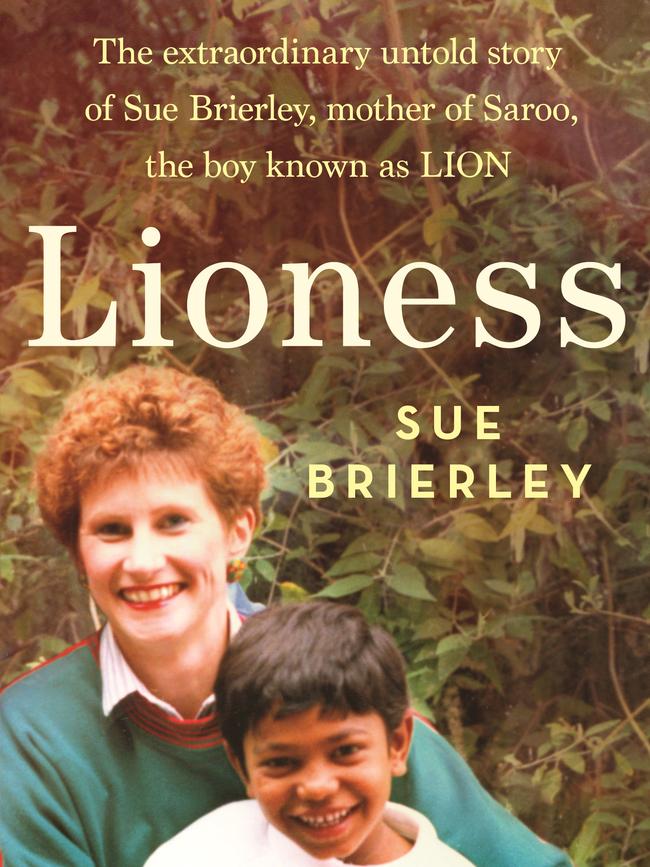

Through the film Lion, the world fell in the love with the story of Saroo Brierley, who found his birth family via Google Earth. Now it’s his Hobart mum’s turn to share her heart-rending story.

As a mother, Sue Brierley is a lioness.

And now, for the first time, the woman played by Nicole Kidman on the big screen is revealing the story of her difficult childhood and the ways it shaped her attitudes towards motherhood.

It is not by accident that the steel-willed Tasmanian became such a fiercely dedicated mother, protector and provider to Saroo, whose lost-boy life story inspired the film Lion, and his younger brother Mantosh.

Because she is usually such a private person, Sue thinks her new memoir, Lioness, may shock even longtime friends, especially when they confront details of her squalid childhood living in a car-wrecker’s yard in the state’s North West.

In the book, the 66-year-old also reveals what really went on when Saroo’s best-selling autobiography, A Long Way Home, was filmed in Hobart five years ago.

If you are thinking it was one big happy family comprising the Lion film makers and the real-life Brierley crew, think again.

The release of Lioness this week was timed to coincide with Saroo’s new children’s book, Little Lion, an illustrated version of his astonishing mission to find his birth family.

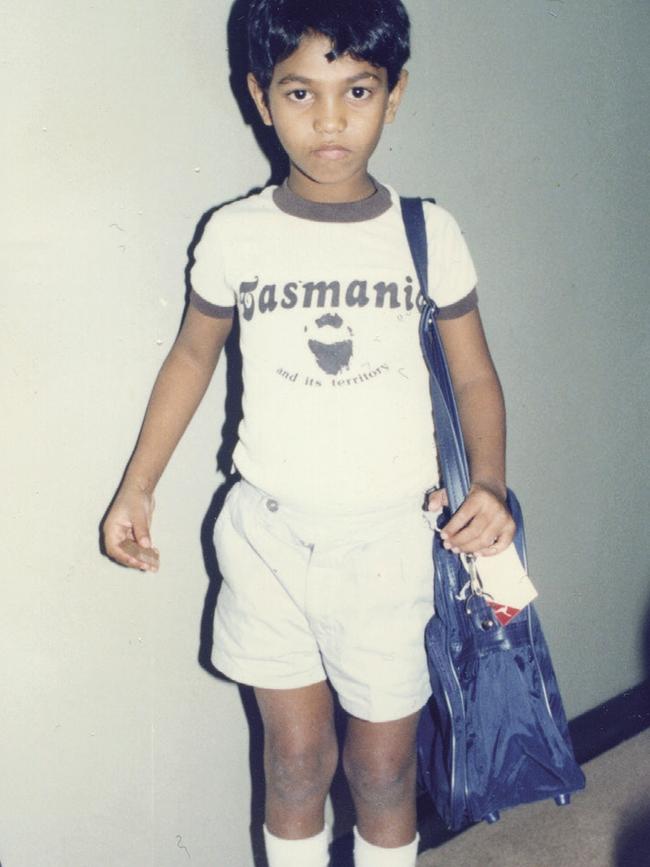

It was in 1986, aged five, that Saroo was separated from his elder brother Guddu at a railway station and became hopelessly lost after catching a long-distance train. Surviving on the streets of Kolkata until he was taken to an orphanage, Saroo was eventually adopted by Sue and her husband John, growing up in a close-knit family before embarking on the life-changing virtual odyssey on Google Earth that made world news.

The pivotal point in Saroo’s story is when he manages, after years of night-sleuthing, to correctly identify his birth family’s village from a few scant details, including a water tower, leading to a profound reunion with his birth mother after 25 years.

In Sue’s life story, a transformational moment is her prophetic vision of a brown-skinned child coming across a field towards her.

The incident may be too ethereal for some readers to grasp its defining quality, but for others Sue’s demonstration of trust in female intuition and the universe and its sometimes cryptic messages will resonate strongly.

“Tears still wet on my face, I looked down by my side and saw a dark brown face …” 12-year-old Suzanne Stelnicki wrote in her diary.

“Could this be meant for me? Oh, how happy I would be!”

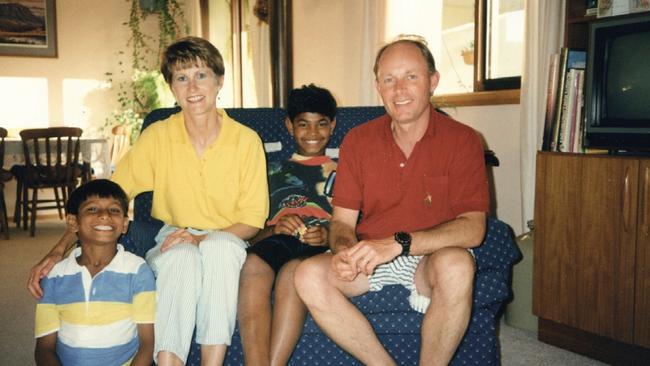

We meet at Sue’s Eastern Shore home, where she has lived for the past 15 years with her beloved husband John.

It’s just a block and a half from the home where they raised Saroo, now 39, and Mantosh, whom they also adopted from India.

It takes a few minutes to adjust to Sue’s unusual energy.

Astute and intense, she is not given to small talk.

Seated in her lounge room, we get straight down to the business of the day.

I find myself less thrown than fascinated by Sue’s demeanour.

Having just read her book, I have more than a glimmer of what exists beneath the former pharmacy beautician’s expertly applied make-up, perfect nails and neat-as-a-pin clothing.

Over a long conversation in armchairs overlooking the River Derwent and the mountain, Sue’s reserve drops away and I realise she was probably just wary.

She tends to hold herself a bit apart from others, she says at one point, and to some degree it’s self-protective.

She knows she’s not your typical go with the flow Aussie mum at a barbie – and that people don’t always like or get where she’s coming from.

Today she is nervous, she confides, wondering what she’s got herself into by signing on the dotted line with Saroo’s publisher, Penguin, to spill her beans.

It was Saroo’s idea, she says, and she feels his absence keenly today.

She wishes he were here to metaphorically hold her hand; but when we meet he is stuck in COVID quarantine in Brisbane.

One of Sue’s goals, she writes in her book’s introduction, was to answer more of the “why” in their story of overseas adoption, her vow to become a mother only through adoption, and the reasons it took decades to fulfil that desire.

Saroo’s story in A Long Way Home was all about searching: his initial search for a place of refuge after he became separated from his family and lived on the streets of Kolkata, which brought him across the world to John and me, and then his virtual and physical search that took him back to India to his birth family.

“Lioness also tells of a search: the years I would spend finding my sons through overseas adoption and creating our family, a life far removed from the one I’d had as a child of European refugees living on the poverty line and living in the long shadow cast by family violence.”

Sue Stelnicki was born in Burnie Hospital on May 14, 1954, six years after her Hungarian mother, Julie, and Polish father, Josef, immigrated from Germany to Australia aboard the SS Castel Bianco with Sue’s older sister, Maria.

“Given that my parents had requested to travel to Canada, they were shocked to learn, halfway through the arduous, slow voyage, that the ship was bound for Australia instead,” Sue writes.

“Somehow in the bedlam of exodus and translation the ultimate destination was confused.”

Family life for the Stelnickis was dominated by her father’s erratic behaviour, flawed business plans and growing brutality towards the rest of the household.

The family’s Somerset farm cottage was surrounded by Josef’s car-wrecking yard, and life was not much better inside the home.

“Rusting hulks of cars covered acres and acres of our land, teetering precariously on each other amid broken glass, tyres, engine parts, wild blackberry brambles and overgrown weeds,” Sue writes.

“For a certain kind of DIY enthusiast or car restorer, the wrecking yard was a goldmine. But for Joe’s wife and daughters, it was an eyesore, a fire risk and a death trap. It looked like some type of post-apocalyptic graveyard.

“The fact that my childhood played out against the backdrop of a wasteland is not lost on me. (It might explain my fanatical love of gardening: outside my house today is a beautiful, vast rose garden, a far cry from the outlook of my childhood home.)”

The only blessing of Sue’s childhood seems to have been the arrival of her younger sister Christine two years after her.

The girls, who remain close, were best friends and allies, inventing games and entertaining themselves however they could in the absence of positive parental attention.

Mentally unstable Josef was beset by chronic grandiose fixations that kept the family on the poverty line.

“My father was not a good provider for his family,” Sue writes.

“He managed all of the finances with an iron fist, always prioritising his own needs over ours, even though he lacked the education necessary to be successful in his business pursuits.

“Mum, my sisters and I survived on any crumbs that might be dropped by him, supplemented by the small amounts of money my mother earned from selling the milk from her two jersey cows.

“From a very young age, I was made to believe that children were incidental — that their purpose was to work hard and support their family, rather than the usual situation where parents work hard to provide for their children’s needs. Even so, I sensed my parents had everything the wrong way around and I knew that this was not how I wanted to treat my children if ever I had my own family one day.”

Over time, her mother’s wretchedness fuelled her father’s violent rage.

“It was a terrifying time for all of us,” Sue writes. “And when he did explode, Maria, Christine and I would descend into panic, not knowing where to hide to escape the horror of what would inevitably eventuate as he would stand menacingly over our mother. Trying to pull a huge man away from his wife led to many bruises for us as well.”

When he was not terrorising them, Josef would undermine them in other ways. To keep his wife trapped on the farm, he sold the car Julie was learning to drive in. And, Sue writes, he even made the bike she and Christine cobbled together to ride among the car wrecks disappear.

“As soon as he realised one of us was trying something new and gaining a little pleasure and independence, he would come and destroy it. There seemed no way to escape Joe and his life-wrecking dreams.”

On one bitterly cold night, 12-year-old Sue stood on the back porch, a place to which she sometimes retreated to try to clear her mind, gazing out at the moon and stars. The night was so clear, she remembers, that she could see a far distant glow of Melbourne across Bass Strait. When she squeezed her eyelids shut, colours and patterns danced before her eyes.

“In the middle of this teary-eyed kaleidoscope I saw a vision of a child,” she writes. “The child had brown skin and a glowing face, and was coming straight towards me. I could not tell if this was a boy or a girl, but within seconds I felt the calming presence of my child beside me, sharing the most wonderful warmth with my shivering body. Beautiful dark eyes looked at me with love and happiness. Was I seeing my future?

“Within a few moments I decided I had, in fact, seen that something wonderful would come of my life. I felt I should shout my thanks to the heavens. I now had a precious secret to hold within my heart.”

In that moment, lost and frightened little Sue Stelnicki was somehow reborn.

“Though I’d seen my father destroy everything I held dear to me — my family home, the pristine wilderness around us, our family bonds — slowly but surely, with the vision of the child of my dreams, I was beginning to believe that new life would be possible.”

Today, Sue still has some of the household items she began to collect for her glory box from that time on, bought with pocket money she earnt working after school at a shoe-repair shop.

“They are precious reminders,” she writes, “of the time I was on the cusp of my old life and the brand-new life opening up in front of me. That box became a kind of family nest in miniature, as I acquired new little treasures, imagining the marriage and home I would one day have.”

Forced by her parents to leave school and start contributing to household income after Grade 10, Sue found a job as a trainee sales assistant and beautician at a Burnie pharmacy. With the care and kindness of the chemist store owner and staff, Sue began to gain in confidence and hope as she developed a sense of self-pride and agency and found solace in friendships and great literature. When she received a pay rise, the 16-year-old thought all her Christmases had come at once.

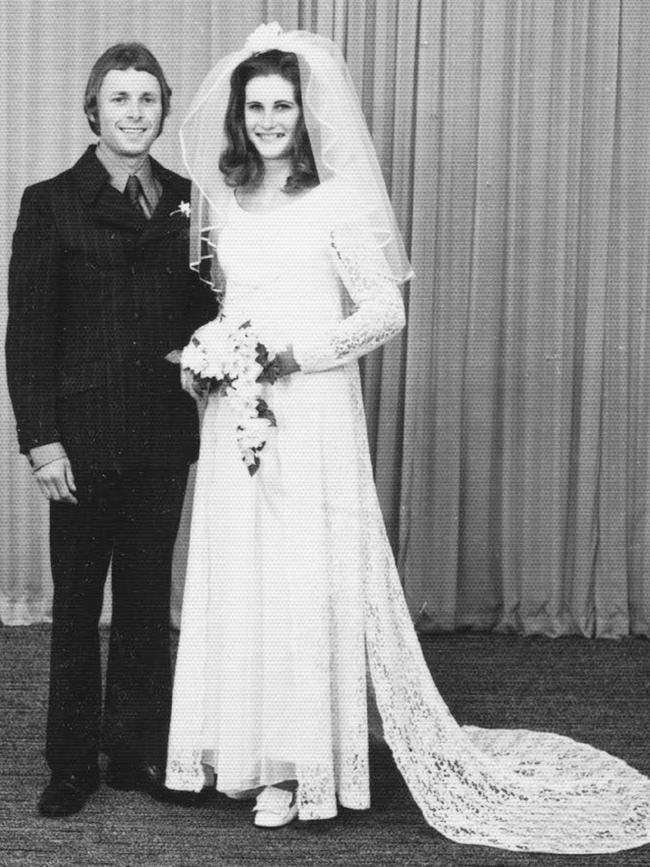

“Little did I know that soon, one day during my lunch hour, my life would improve even more dramatically,” she writes of meeting husband John, a young department manager at the town’s Coles variety store.

One evening, Sue was about to go on an after-dark tip run with her father and Christine when the phone rang.

“Despite my nerves, I listened calmly as John introduced himself in his distinctive English accent and asked if I was free to go and see a film with him that evening,” she remembers.

Adopting, Sue says, was always her only plan for motherhood.

In John, she found a fellow traveller. And that, she says, has made all the difference.

“I’m not one to change my mind,” she says with a little laugh. “In life, it’s not that easy to stick to your vision and not be manipulated and controlled by society, life and time. All those factors really contrive to change one’s mind, but I was fortunate in that I had someone by my side who was also very committed.

“Let’s face it, if I’d met up with any other guy, it would not be likely that I could have kept my soul promise. So it’s not just me. It’s also my husband John — and we’ve just not long celebrated 50 years together. I often thank the heavens he came into my life when I was 16. While the rest is history, it would not have happened without said union.”

In 1987 Sue and John had been married for 16 years when they decided to look into overseas adoption once more, having been put off some years previously. Now a few small policy shifts gave them renewed hope.

When they heard they were indeed eligible to adopt a child from overseas, Sue began to write a journal.

“I was determined to have my own version of an expectant mother’s diary, just like pregnant mothers, while we waited so I could share every detail with our child in the future.”

In that first diary, she describes Monday, July 27, 1987, as “a most exciting day!” A case worker had rung to tell them about a six-year-old boy named Saroo who needed a new family.

When they saw a tiny passport photo of the little boy the next day, Sue says she and John knew he would become their son. “At that moment, Saroo surged into our hearts and souls as truly as if he were born within and for us,” Sue writes.

Five days after our interview, I catch up with Saroo by phone after he flies back into Tasmania from interstate.

He’s in good spirits, having just seen Little Lion in print for the first time.

When I say his mother’s commitment to wait, however long it took, for her Indian sons to come into her life reminded me of his doggedness searching for his birth family via Google Earth, he laughs in agreement.

“We share that strong trait of determination,” he says. “Once you have it you are like a dog with a bone. You are never to let go. It’s not something simple to you. You are thinking about [your goal] continuously and it becomes apparent that you are entranced with it. It’s all or nothing at the end of the day.

“There is no one on this Earth who could pay you out diamonds, gold, platinum, money [to change course] simply because they want to see you with a freer mind, a better day … Once you are determined you cannot stop.”

Like the film, his children’s book Little Lion takes its title from his original name, Sheru, which means Lion in Hindi (“Saroo” was the way he spoke his own name as a child). He says he loves the book’s illustrations of butterflies throughout, which symbolise his eternal bond with and the spiritual guidance of his adored elder brother Guddu, who died after being hit by a train on that long-ago night they became separated.

“As you probably know the movie was dedicated to him, and the first book, too,” says Saroo. He says he will honour and grieve Guddu forever. “I will never let it go, but I am not taking it on as a burden. Back then he was the father figure I looked to, the man, and I saw kindness and guidance, and somebody who could lead.”

Little Lion is dedicated to Sue. “The world has recognised me for what I’ve done and my story became an inspiration to people around the world,” Saroo says, “but you’ve got to understand that to a son or daughter there is a keystone.”

He says Sue’s guidance has had a profound impact on his life, paying tribute to her conscientiousness as a mother in trying to meet every special need of her boys.

“I had the will and power to learn from her and create who I am,” Saroo says. It was a gift “to have such a powerful woman bringing in a child to love and accept and be in her heart forever, and also acknowledge he has baggage and impurities in him against his wishes”.

A strong sense of their deep connection emerges; it seems mother and son are not only entwined in a shared history but bonded by a shared metaphysical approach to life, their beliefs tending towards a kind of spiritual fatalism.

Saroo thinks readers will take his mother’s book to heart.

“I think it will be nourishing to people,” he says. “It is so wholesome and contains so much wisdom. It is so emotional. And it is very confronting.”

Though he knew bits and pieces about her childhood and knew it was hard and formative, this is the first time Saroo has seen the jigsaw put together. He is full of admiration for her.

One thing Saroo has always known about his parents’ lives is that adoption was not a fallback position for them because of infertility.

It upsets Sue that this was not conveyed in the film.

In a memorable Lion scene, “Sue” (Kidman) is all cried out and at her wits’ end over Mantosh’s troubled ways as a young man.

Trying to comfort her, “Saroo” (Dev Patel) says he’s sorry she couldn’t have her own kids, that she had to adopt children that were not “blank pages”.

“What are you saying?” the actor says, slowly turning her head to look at him with great intensity.

“I could have had kids. We chose not to have kids. We wanted the two of you in our lives. That’s what we chose.”

While acknowledging Kidman’s powerful performance, Sue was upset by the scene.

“The way you saw it in the movie was actually not authentic because my boys always knew they were first choice,” she says.

“But with the whim of movie makers, it was shown that Saroo was not aware of this situation.

“That was my power and it was lost because it wasn’t a truthful rendition of the fact — and I’m very pedantic about truth and fact.”

She says that in Lioness she attempts to correct the record. The film’s dramatic liberties have caused her no small angst.

“Really, I just wanted to tell the truth, my truth, make corrections to what was being put out there,” she says. “I thought long and hard about it, and John and I talked … and Saroo thought it would be good for me to let it all out.”

She had hoped, perhaps naively, that the family might somehow be part of the filmmaking process when scenes were filmed around Hobart, but the film had a momentum and direction of its own and the crew rarely called on the family.

“We thought that would be a healthy thing and secondly we thought it would be damn fun,” Sue says. “’Hey, aren’t we entitled to a little bit of pleasure out of our story and the sharing thereof?’”

Having been treated “like royalty” when 60 Minutes filmed Saroo’s story previously, Sue says the family felt cold-shouldered by the makers of Lion.

“Anything that happened for us, anything we enjoyed, was basically because we forced ourselves into it,” she says.

The family attended both the world premiere of the film, and the Academy Awards, when Lion was nominated for eight Oscars. But Sue still smarts over the experience.

“It was such a disappointment and such an insult,” she says. “Really, if Nicole Kidman hadn’t embraced me as part of the process, I don’t know how we’d have endured that.”

The pair became friendly during filming, with Kidman — also an adoptive mother and Sue’s first choice to play her in the film — still keeping in sporadic touch.

Penguin sent the actor a copy of Lioness.

“I’m sure she will read it,” Sue says. “She has been very encouraging to me through the process. Nice, kind, words, ‘Don’t worry Sue, it’ll be fantastic, like you are’.”

Sue laughs. “She really is a nice person.”

Over the years, Sue has tried to lay some old ghosts to rest.

Writing the book has helped that process — when it hasn’t hindered it, she says. The reprocessing of her childhood sometimes felt as traumatic as it was cathartic.

“It wasn’t a pretty picture,” she says. “They were terrible early years, don’t get me wrong, but they were an opportunity to learn how to be better and how things could be better.”

She says her spiritual beliefs and esoteric reading are great sources of strength. “Through all that time I’ve been a very avid reader,” she says. “We’re a little bit tail-end hippie. We’ve got a different perspective. I would hate to think I’ve lived my life as a victim.

“I do consider myself a recovered Catholic, but my reading and belief in this other spiritual world has been a great resource for me and supported me in everything I do, really …

“Sometimes I feel the gift of an energy and an understanding. Not like voices, but I do get a feeling of ‘hey, chill, this will be all right’.”

Something she cannot abide is the suffering of children. Though doubtful it will happen in her lifetime, Sue wants to see adoption and foster systems overhauled in Australia.

“There’s a whole bunch of people who should never be parents, and it’s quite liberating that I feel free to say that sort of thing now,” she says.

“We now know what profound effects that has on a child if they are lumped in a bad family … As we speak, children are dying because of the lack of good parenting. I feel that very strongly and it’s a shameful thing.”

She wants to see more children who are in need of long-term care permanently adopted into families rather than passing through sometimes numerous foster homes.

“We can’t just store children in foster families perchance that their parents might lift their game and be worthwhile enough to parent their children again,” she says.

“We need to start lifting the profile of adoption and thinking of it with respect, not as a second-choice thing primarily as a service for people who are desperate to have a child through infertility.”

Sue does not expect to sell a million copies of Lioness, following in the padded footprints of A Long Way Home.

“I don’t know where it will go,” she says. “I’d like to sell enough so that it wasn’t a waste of my time. If it sells, it’ll mean that people are awake to a different perspective on humanity and that would make the project worthwhile.

“If it’s a flop, well, it’s just been a very traumatic and difficult three years of my life.”

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Lauderdale FC hold fundraising event for Ryan Wiggins

Lauderdale Football Club is holding a special fundraising event to raise funds for footballer Ryan Wiggins following a tragic accident that left him with a spinal injury two weekends ago. LATEST >>

Removalist company goes bust as Tasmanians wait for belongings

A national removals company who has left Tasmanians waiting weeks for their belongings has been placed into liquidation. LATEST >>