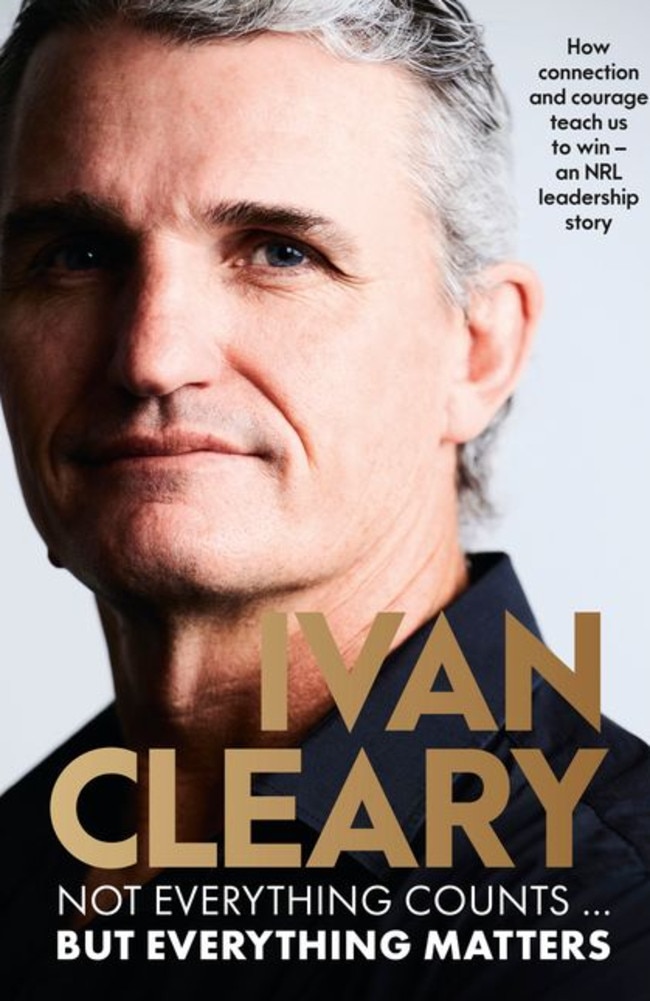

Ivan Cleary: Not everything counts but everything matters | Book extract

Ivan Cleary is not just the history-making coach at the heart of Penrith Panthers’ stunning success – he’s also the father of star player Nathan. In this exclusive extract he opens up on his son’s high-profile relationship with Matildas star Mary Fowler.

Ivan Cleary is not just the history-making coach at the heart of Penrith Panthers’ stunning success – he’s also the father of one of its star players, Nathan. In this exclusive edited extract from Ivan’s new book Not Everything Counts ... But Everything Matters, the two go head-to-head on being a team, on and off the field.

IVAN ON NATHAN

Even though my eldest son had the potential to be a good footballer, I assured him that he didn’t have to play professionally if he didn’t want to. He could be whoever he wanted to be. He would always have his family’s support.

But he just loved the game – and he loved playing it.

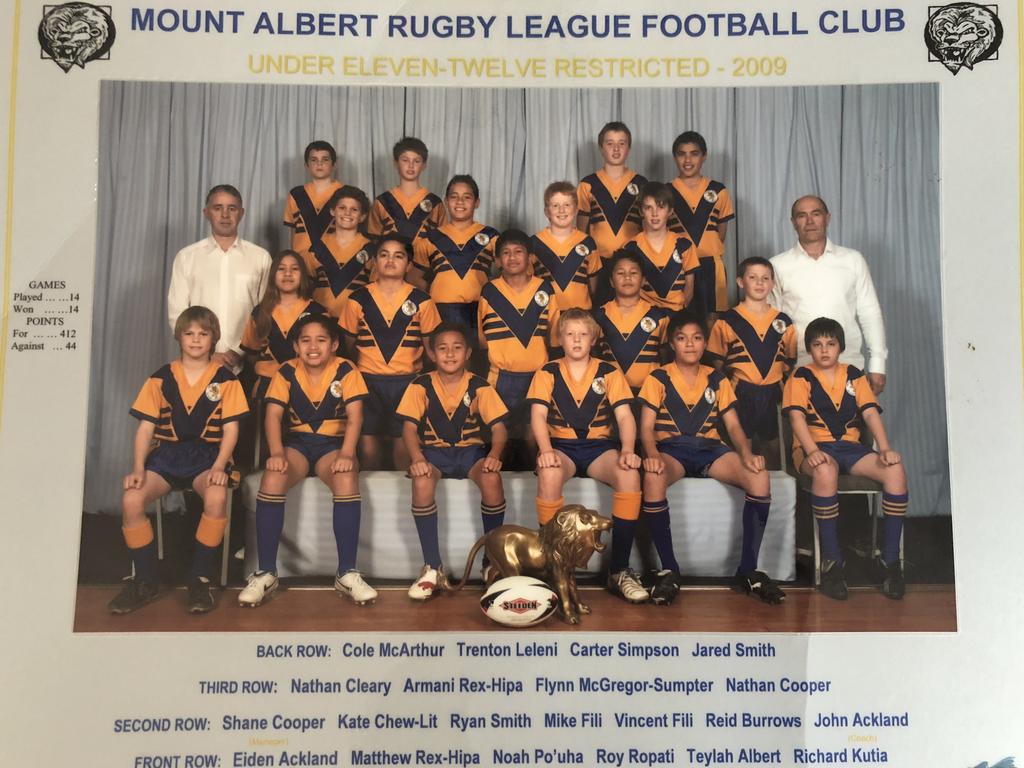

We lived in New Zealand for much of Nat’s young childhood, and it was a great place for him to start playing rugby league. A few years of restricted-weight footy was the perfect start; and just a handful of years later he would be an NRL player.

When he was rising through the junior ranks, I let his coaches coach him. I was a silent father on the sideline. About the only things I would discuss with Nat and his younger brother, Jett – also a halfback – were the fundamentals: be a good teammate, tackle hard, compete strongly, be accurate, and, if you do that, your talent will take over.

As the Warriors’ head coach, and having my sons in junior grades, the last thing anyone needed was me being overbearing, awkward and intimidating. I was always mindful of being that guy.

A young player’s career can take off so quickly. When Nat was 17, he was picked at five-eighth in the Australian Schoolboys’ team for the 2015 international series against New Zealand. The Australian side included quite a few stars of the future: Melbourne’s Ryan Papenhuyzen, North Queensland’s Scott Drinkwater, South Sydney’s Cameron Murray and the Cowboys’ Reuben Cotter.

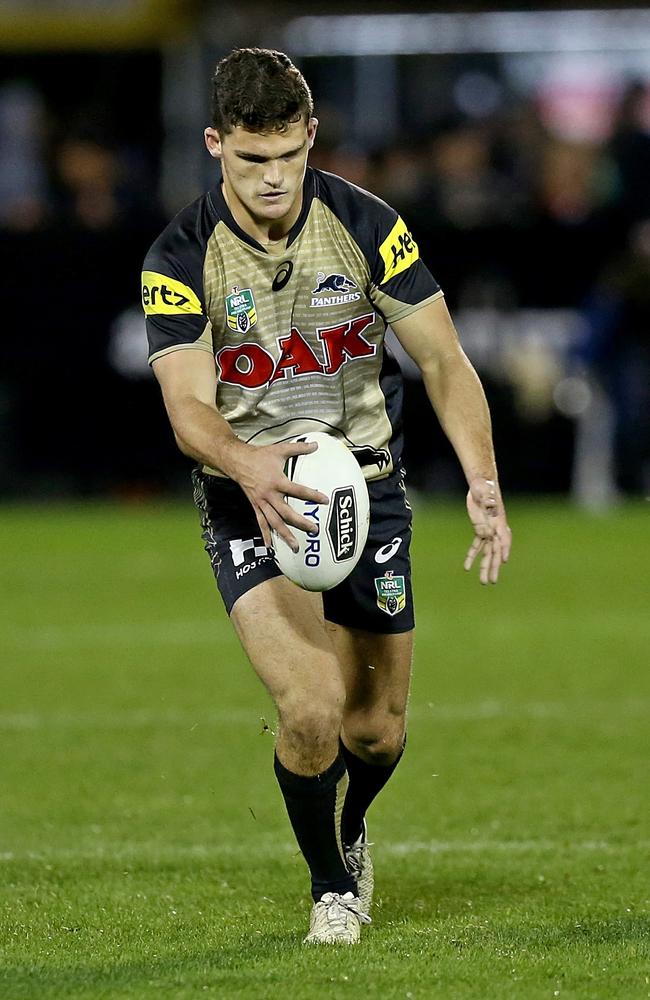

By this time I could see Nat having a good professional career, but I didn’t expect him to make his NRL debut for Penrith at the age of 18. As it happened, one silver lining of me being sacked by the club in 2015 was that it opened the way for Nat to make his debut.

At the time I was shown the door, Nat was playing under‑20s. We’d spoken about him debuting in first-grade when he was 20, which I thought was a realistic timeline.

I would never have debuted him at 18. He still ribs me about that.

The coach who replaced me, Anthony Griffin, wanted him in first grade straightaway, even though Nat had only played one game of reserve grade. And so, in June 2016, he selected Nat for the Panthers’ Round 13 clash with the Storm in Melbourne.

Really, Nat couldn’t have been given a tougher debut.

He was playing at five-eighth and the Storm ran at him all night, forcing him to make 38 tackles. I remember seeing Storm halfback Cooper Cronk talking to him at the end of the game, giving him a few tips. That was classy of Cooper, even though he’d just sent traffic at him all night.

I helped Nat manage his contracts and his money. My advice to the parents and managers of young players is not to seek a big-money contract too soon. They all look at me like there’s something wrong with me, but there’s a reason I say this.

While these offers can be very tempting, in my view they aren’t always best for a player’s development. As soon as a player gets a certain amount of money, they feel pressure to live up to that number. They have to produce or they’ll consider themselves a failure. And if they don’t have instant success, the pressure can be overwhelming.

That’s especially true when the player is a young halfback or five-eighth, with the responsibility of leading the team’s attack. The increased expectations can be a heavy weight to carry.

Early in his career at Penrith, Nat took less money than he could’ve got elsewhere.

‘Isn’t he worth more than that?’ my wife Bec asked me.

‘He is,’ I said. ‘But I know what it’s like to have the pressure of a big contract.’

Everyone at a football club knows roughly what you’re getting paid. The board, the coaches, the other players. You need to be mature enough to handle that. That’s why it’s better to start small. If you’re good enough, the money will come – and if you’re patient and set a sound foundation, you’ll earn a lot more over the long term than you will from one big contract as a youngster.

Not many have taken my advice, I have to say – but how many players have you seen sign a massive contract early in their careers and then fail to live up to it? The pressure can become too much for them.

By April 2017 I was in charge of the Tigers, and having to coach against my son pained me. It happened once that year, and then again in 2018. Penrith won both times but I hated it. Bec and our kids hated it too.

I would never have come back to Penrith as head coach if Nat was a fringe first-grader. That would have been too difficult for me, and I’m not sure how I would have handled the inevitable accusations of nepotism. But by the time I returned, he’d established himself as one of the NRL’s best players. In 2018, he had been part of Brad Fittler’s new-look New South Wales team that won the State of Origin series against Queensland. He was already a permanent fixture in Penrith’s best side before I arrived, which made things easier for me. At no stage did I ever think, ‘I can’t pick him.’

While I’m coaching Nat, he’s usually just another player, but there are brief moments from time to time when he becomes my son.

A friend of mine has a business in New Zealand, and all his children work for him. ‘Of all my employees,’ he once told me, ‘they’re the only ones I truly trust.’ That’s so powerful. It doesn’t matter who you are or what you’re trying to do, there’s nothing like having absolute trust in someone. That is what Nat and I share.

During our rough season in 2019, some outside the club were suggesting that I should drop Nathan. That was a really tough time for him, as he had ‘FOPO’ – ‘fear of people’s opinions’. When he was playing, he worried about what people were thinking, trying to anticipate how they’d judge whatever he was about to do, wondering Am I playing shit? In his own words, it was ‘paralysing’.

After matches, it would get worse. Nat was constantly going on his phone, reading comments people made about him on social media. He’s grown beyond that now, through

conscious effort. One of the most important things he did was to work out who his circle was, and to tell himself that their opinions were the only ones he respected. If you weren’t in the circle, your opinion didn’t matter. That made sense to me: if you don’t take advice from someone, why take their criticism?

If Andrew Johns criticised Nathan – which he has done in the past – that would sting him. But if a commentator or journalist he didn’t respect said something negative, he wouldn’t care.

These days, Nathan coaches the rest of us on how to shut out what other people say about him. ‘Don’t read it,’ he tells us. ‘And if you do, remember that I don’t value their opinions.’ His aunties are the type to fire back on social media. They never want to see him cop any sort of abuse.

I’m not on social media, but I’m the same – the criticism he gets from mainstream media still stings me. I try to take his advice, though, and ignore it. His courage helps the rest of the family navigate a way through that noise. It’s pretty cool to see your kids mature and teach you such great lessons.

At Origin time, the pressure and scrutiny reach another level. It’s the time of year when I go from being his coach to being his dad. At the Panthers, he’s just another player. In Origin, I’m his dad. I spend most of the match watching him.

I like that Nathan plays tough. He’s carried plenty of injuries in big matches. In the 2023 grand final, he did the posterior cruciate ligament in his knee in the 10th minute, but you wouldn’t have known. That’s an injury that can take players out for as much as six weeks.

In 2021, he dislocated his shoulder early in the second Origin match, at Suncorp Stadium. He played out the match, played strong and the Blues won 26–0. That’s real Origin stuff.

I see the influence Origin has on players at club level.

As at Origin level, it took Nat a little time to feel comfortable playing for Australia, especially taking over at halfback from a champion like Daly Cherry-Evans. Nat’s the kind of guy who really respects the older players in his team.

At the 2021 Rugby League World Cup – which, because of Covid-19, was played in 2022 – Nat needed to feel his way in the Kangaroos. He’s always been like that: he’s often needed

a game at each new level to find his feet, and then he takes off. He had to adapt to a new lifestyle on tour, too, where there was a bit more going on in between games. The longer

the tournament went on, though, the more Mal Meninga, the Kangaroos’ coach, let Nat take control of the team. When they beat Samoa in the final, and he played well, it was a relief.

Bec and I feel the pressure when he plays. The whole family does. We feel the nerves because Origin is win or bust, especially for the halfback. If New South Wales loses, it doesn’t matter how he went – he’ll cop it.

Nat also owns his mistakes. In 2022, he dumped Parramatta’s Dylan Brown on his head in a dangerous tackle. He was sent off, and later suspended for five matches, but he knew straightaway that he was in the wrong.

He gets more public attention than any of the rest of us because of what he does. He doesn’t get distracted from his job by taking on too much outside of football, even if it costs him money.

Nat has three contracts outside of footy: his beer company, Drink West, Channel 9 and Adidas. He was once offered a large sum of money by a car dealership to post an endorsement on social media twice a year, including during the Origin series if he was selected. He only did it for one year, then pulled out of the deal. Most people would have seen it as easy money, but he didn’t want any unnecessary distractions as he prepared for one of the biggest games of his life. I understood that.

I’ve also been impressed with how he’s handled the media frenzy that’s come because of his relationship with another high-profile athlete, the Matildas’ Mary Fowler.

She’s impressive, too. Their relationship has been on their terms, and I think that’s really cool. I’ve heard a lot about how these things work now: hard launch, soft launch, Insta official.

My mates keep asking me what it all means. I don’t know.

NATHAN ON IVAN

There are times, even now, when I find it strange listening to Dad address the playing group. This is so weird – that’s my dad up there talking! When we’re around the football team I call

him ‘Dad’, but if I’m talking about him to someone else, or calling out to him from a distance, I’ll call him ‘Ivan’.

Over time, our relationship within the football environment has found a good balance. He treats me the same as every other player. If anything, he’s reluctant to praise me for the good things I do, leaving that to the assistant coaches. He’s cautious about favouring me in any way – and I love that. What helps is his relationship with the rest of the players. He treats them like they’re his sons too.

The defining characteristic of Dad’s coaching is his authenticity. He’s true to himself and his values, and he’s created a safe environment in which everyone else can do the same. People can be who they are. They can be vulnerable. That vulnerability takes a team’s culture to the next level. Dad is caring and shows his players respect, and they feel that. He doesn’t care about what those outside the club think, or worry about the spotlight and accolades. His focus is on creating a winning team culture.

He also doesn’t give much away. I wasn’t aware in 2019 that he was thinking about walking away, or that he was suffering depression. It’s not in his nature to open up about these things, but Mum has played an important role in drawing him out and helping him show that vulnerability.

And that’s been important. It’s allowed him to connect with people in a new way – including me. I’ve been able to see him in a different light.

When he was offered the opportunity to return to Penrith, we were amazed it even happened. We didn’t really take on what the repercussions would be if we didn’t win matches.

It was just awful, really. When he arrived, Dad thought it was all going to fall into place, but I was in the worst form of my career. We lost against the Warriors and I was pretty much in tears. I looked at him, and he looked back at me with a blank face I’d never seen before. It was a tough moment for our team and our family.

But that 2019 season, when Dad was struggling so much with his mental health, was a defining moment in our relationship. When you’re a kid, you see your dad as a superhero. It’s only as you get older that you realise he’s vulnerable like everyone else. We got through those tough times and now we talk more about what we’re really feeling. It’s made our relationship stronger. I didn’t know about his depression then, and I probably don’t know all there is to know about it now, but I’m proud of him for getting through it, and even prouder that he’s speaking out about it.

I think it was this difficult time that drove Dad to create the culture that turned our club around. We realised our actions off the field were just as important as those on it.

It wasn’t hard for us to buy into the cultural change Dad introduced in 2020. There was some player turnover, with a younger generation coming through. It was a fresh start. We knew, after what had happened in 2019, that we had to buy in to what Dad was telling us, otherwise there would only be more of the same.

From the first day of pre-season, we locked in. From the get-go, everyone was heading in the same direction, which is so important in a football club: we all knew what we wanted, nobody was pulling the other way, and everyone gave themselves over to the team.

Even so, we could never have imagined that it would work out as it has. If you’d said to me during that 2020 pre-season that we’d win all these premierships, I’d have laughed at you.

Yet Dad instilled a belief in all the players that if we followed the path he set for us, good things would come. I still pinch myself every day. I try not to look back too often, though, because we’re always looking ahead to the next game, trying to be better. There’s time to reflect when you retire.

Taking on the co-captain’s role has been interesting. I always wanted to be a leader but didn’t know if had the right qualities. I just knew I wanted to work hard at being someone who could have a positive influence on the group.

I’m introverted, like my father. The hardest thing for me is feeling something but not having the skills to say it to the group. I get that nervous feeling in my gut. But I’ve worked on that and now I’m more confident speaking up. We’re all mates. We all want the same thing. What I’m feeling might not be the perfect thing to say, but if you’re feeling something and you don’t say it, you’ll regret it.

It helped that Isaah Yeo, James Fisher-Harris and I started our leadership journey together. Dad said he didn’t want us to do it – he needed us to do it. He wanted us to be the bridge

between players and coaches. He told us that the role we had to play was important to the success of the organisation.

That’s another thing I appreciate about Dad’s leadership: he collaborates, working with everyone in the club. He’s the boss, and he’s firm on how he wants things done, but others

have a say. It’s not his way or the highway. We’re a big, happy family when we’re moving in the same direction, but we can go to him if there’s something we disagree on and discuss it openly.

I once looked at leadership as something individual, but now I understand that we all need people to lean on. You can’t do it all yourself. That’s something Dad models well.

He allows his assistant coaches to coach and wants them to get as much credit as he does. We have a strategy meeting once a week, where the players’ leadership group meets with

the coaches. We discuss what they want from us, and what we think is working and what’s not.

Building relationships is the most important part of leadership. To understand how to get the best out of the people you’re playing with, you need to understand who they are. Some players need a spray on the field when they’re not performing well; others prefer to be pulled aside and asked questions.

The most satisfying part of everything we’ve achieved at Penrith is how we’ve become a source of community pride.

When I was a young player, Dad told me that you could make someone’s day by how you played on the weekend.

These days, when I walk around town after a win, I can see it on people’s faces. That brings pressure with it, but it’s a privilege to have such an effect on people.

Connecting with our community is our superpower. We represent so much more than ourselves.

As a team, we try never to look back at what we’ve achieved. We look forward instead, as the next thing is always rolling around. But you can only look forward when everyone parks their ego, and no one’s resting on the achievements of the past. We drive each other so hard to be better every day, no matter the result on the weekend. We’re always finding ways to get better – and we enjoy it. Why wouldn’t we keep growing as players and as a team if we

can? We want to stand out from the rest.

The way we train is the way we play. The right preparation gives us confidence for the game, and it means we don’t have any excuses for our performance. Sometimes it’s our day, sometimes it’s not, but we can live with that because we’ve done everything we can to put ourselves in the best position to succeed.

I’m proud that, on the biggest day, when we were under the most pressure, facing the greatest adversity we’d ever faced, that preparation paid off. When we were down 24–8 against the Broncos in the 2023 grand final, we still had the belief that – somehow – we could win. That came from our culture of not giving up. The work we had done on the mental

side of our game meant we were always in the moment. We all trusted in the player next to us and fed off each other’s energy.

Each time I play a game of football, I want to make Dad proud – as a coach and as a father. But I know he’s proudest of me when I’m putting in the work, preparing hard, doing the best I can.

This is an exclusive edited extract from Not Everything Counts ... But Everything Matters, by Ivan Cleary. It will be published by HarperCollins on October 16 and is available to pre-order now.

Ivan Cleary will launch Not Everything Counts ... But Everything Matters with a free in-conversation event at Penrith Rugby Leagues Club on October 16, 5;30-6:30pm. Get your free ticket here.

Catch Ivan and Nathan on Mark Bouris’ podcast Straight Talk, wherever you get your pods.

More Coverage

Originally published as Ivan Cleary: Not everything counts but everything matters | Book extract