Andrew Rule: Hughie Wilson’s violent death lingers over Colac and Victoria Police

Hughie Wilson’s ugly end is not well known outside the district where he lived and died. What happened to the World War II veteran still hangs over Colac and Victoria Police, a shameful chapter in the history of both.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

This is what some people believe happened the night Hughie Wilson was killed.

Hughie, a lean figure in shabby pants and a gabardine overcoat, is walking along a bitumen road with paddocks on one side and an old brickworks on the other. It’s after sunset and he’s heading for the bush where he lives in a rough camp.

A police car approaches at speed. The driver doesn’t see the slow-moving walker and Hughie doesn’t dodge quickly enough.

The car hits. His body is flung high in the air and comes down, crumpled and broken. The driver brakes and jumps out. The wounded man is alive — and perhaps that panics the driver even more.

If he tries to save the injured man by taking him to hospital or by using the police radio to call an ambulance, it will expose him in too many ways:

As a potentially culpable driver, especially if he has been drinking.

As a wandering husband in the wrong place and the wrong time.

And if local rumours are to be believed, as the unauthorised driver of a police car that’s supposed to be parked overnight at Colac police station.

The suspected driver is a hard man, say those who know him. He has to act fast, before witnesses appear. If the victim is conscious, he might know it’s a police car that hit him and that’s a risk the driver won’t take.

The inescapable suspicion is that he grabs a heavy tool such as a jack handle or tyre lever and approaches the wounded man …

Hughie Wilson, war veteran and bushman, is discovered dead beside the road early next morning. His body, stiff with rigor mortis, is laid out neatly with the legs together and arms beside his sides. On his forehead is a long, oddly straight indentation.

That’s how a young constable found him when called to the scene by a motorist who first saw the body just after dawn on September 12, 1976.

That young policeman never forgot the way Hughie Wilson’s body was laid out, and what it might mean. He knows bodies of people killed by cars are smashed up with crooked limbs, like rag dolls.

Something else: he also sees a side mirror sitting near the body, remarkably undamaged and with no sign of blood.

The odds against anyone ever being charged for killing Hughie Wilson have always been long — much like the chance of charges being laid over the Easey St murders committed in Collingwood just four months later.

But when an arrest was made over Easey St last September, it proved that even after five decades things can change fast.

Death, divorce, DNA matching and time can loosen tongues tightly held for a generation, as loyalties fade but consciences don’t.

Hughie Wilson’s violent end is not well-known outside the district where he lived and died. But people there still talk about it behind closed doors, to those they trust.

What happened to the World War II veteran still lingers over Colac and Victoria Police, a shameful chapter in the history of both.

Local rumours are that there was a cover-up involving former police, many still living, in a conspiracy to protect one of their own. A conspiracy that cynically smeared the good cop who tried to find the truth about Wilson’s death and was hounded for it.

The good cop was Peter Michael Goonan. When he died unexpectedly last month, it marked the end of more than 48 years of his trying to shed light on the ugly death of a man who deserved better.

As the Saturday night of September 11, 1976 turned into Sunday morning, Goonan was a 23-year-old constable in charge of the Colac watch house overnight.

Some time earlier that evening (Goonan and other police later surmised) another officer took car keys from the key cabinet and drove off in a marked police car, a Valiant sedan.

Where that off-duty policeman went and what he was doing is hard to know but the assumption is that it was a private affair, not police business. The station’s “divvy van” was already out on routine patrol, driven by another constable, Gary Thayer.

The man who took the Valiant was known for driving fast, something that came with the territory in a “highway town” where local police had to cover the main road in and out for a long way in each direction.

But Colac has other roads besides the Princes Hwy, such as the one that heads south into the Otways.

Between the town and the Otways bush is the district of Barongarook. These days, it’s dotted with farmlets and lifestyle blocks but in 1976 the population was sparse and traffic light.

It was up here, in the bush beyond the paddocks, that Hughie Wilson had camped alone for close to 30 years. One of a big local family, he was a silent casualty who returned from war service in the mid-1940s to find that life had moved on.

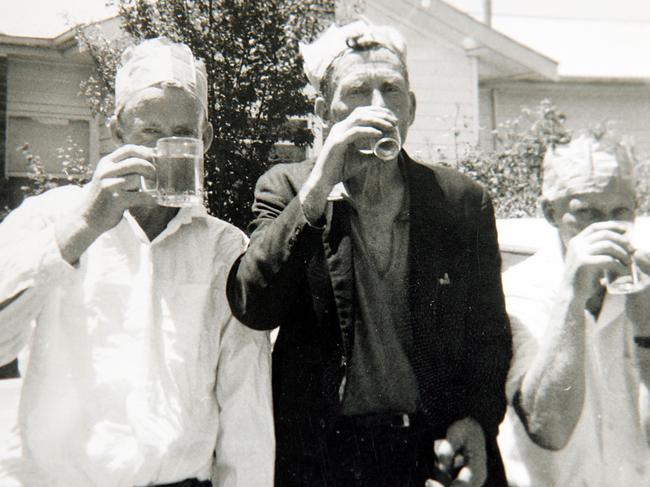

In his case, his girlfriend had married someone else. His life quietly unravelled. He was not a “derelict” or a drunk or notably eccentric. He was something of a swagman, except he had a permanent camp and the road he tramped was into Colac to pick up supplies in the hessian bag he always carried.

He had relatives in town and saw them regularly. He was a kind, gentle man with no enemies.

Peter Goonan was a local boy, too. He’d grown up on the family dairy farm out of town, as did the “school bus” sweetheart he married, Heather Middleton.

There are still Goonans and Middletons around Colac, respected and active in the community.

When Peter Goonans’s mother Pauline died in 2020, she was mourned by members of her parish as the cheerful volunteer pianist at every function since the 1950s.

As a young man, Peter played football instead of piano. He played in the Hampden League before returning to Colac and was known as a staunch defender, which was the key to his character.

Three years after Hughie Wilson’s death, Goonan quit the force and he and Heather ran a business in Colac. Ten years after that, they moved to Queensland to start another business — and to avoid lies spread by people desperate to discredit him.

Goonan didn’t tell his wife and their two daughters everything about the fallout from his ongoing campaign to uncover the truth about Hughie Wilson’s death.

“He kept me fairly separate from it,” Heather recalled this week from the Hervey Bay home they shared until Peter died in early February.

“It was quite traumatic,” she says of the backlash against her husband. “Peter was always one to get the right thing done. But he felt he didn’t get support from his colleagues.”

That’s an understatement. When Goonan fought to revive investigation of the case over the years, he was targeted with renewed rumours and allegations blaming him for Wilson’s death — a brazen bid to deflect attention from what locals see as the Colac cop conspiracy.

Colac police didn’t have a good name in 1976. Some of the officers had already been sprung running a racket, selling driver’s licences to migrants. There were other rackets. A favourite in any regional centre was for police to have a cosy relationship with a panelbeater and a pub.

Police would alert the panelbeater’s towtruck driver to car crashes, in return for cash and beer “slings” and free panel work. While a favoured publican, with free beer and meals, would avoid prosecution for licensing breaches.

In Colac in the mid-1970s, Laneway Panels was so close to the police that locals called it “Colac West police station.” Cops went to the panel shop after hours, drinking or working on cars.

In 1976, Laneway Panels was on the south side of the highway on the west side of town. Its main entrance, big enough for a loaded tow truck, fronted on to the busy road. But the premises has a rear yard opening into a quiet dirt lane that leads hundreds of metres south to a back street leading, in turn, to the Otways road.

In other words, at night a vehicle could come or go in virtual secrecy, idling down the back lane with headlights off.

Laneway Panels was run by one Herb Craddock and a business partner. Craddock died in 2014, after denying at an inquiry that his workshop secretly repaired a damaged police sedan the night that Hugh Wilson was killed. His business partner and various police, serving and retired, also denied knowledge of such a thing.

But a panel beater who’d been called into work on a Saturday night in September 1976 gave sworn evidence at an inquest in 2011 that seemed to contradict his former employers. Colin Blake said he’d worked on a white Valiant police car late at night.

Blake the honest panel beater still lives near Colac. But when the Sunday Herald Sun came asking questions about the case recently, he did not want to poke the bear.

Neither did Pauline Langdon, a local woman who’d seen a police car near where Wilson’s body was found that night. She made a statement later but the part that mentioned the police car was missing, according to a former Colac policeman who sympathised with Goonan.

This ex-policeman, who now lives far from Colac, says there are other witnesses, or potential witnesses, still nervous about talking. He, too, is careful. When he meets the Sunday Herald Sun, he stays indoors and cuts out details that might publicly identify him because he doesn’t want to be persecuted the way Peter Goonan was.

He names one man who saw a police car on the Otways road that night. He mentions a security guard who saw a truck bringing the damaged police car into Laneway Panels later that night.

Other details also intrigue him.

One is that the side mirror found at the death scene was not the type fitted to a Valiant, and showed no sign of being in a collision. It was clearly hurriedly planted as a “throw off” to suggest an unknown car was responsible for the hit-run, he says.

Another memory is of watching the rumoured killer, a policeman he knew well but tried to avoid.

In 2012, a Victorian coroner found there was no evidence to suggest police were responsible for Hughie Wilson’s death. The inquest heard a police car had been repaired around the time Wilson died but police were cleared of any involvement as the coroner found the damage to the car was not consistent with Wilson’s injuries.

Peter Goonan never forgot, either. When he died unexpectedly last month, his family chose this song lyric for his death notice: “Cause It’s A Bittersweet Symphony, That’s Life.”

Goonan the honest cop will get a headstone but Hughie Wilson hasn’t. More than 48 years after he was buried the first time, and 18 years after his remains were dug up for re-examination in 2007, his grave in the Colac cemetery is still bare gravel.

The RSL takes $2bn a year from poker machines in Victoria but doesn’t waste it on a headstone for a returned soldier.

Originally published as Andrew Rule: Hughie Wilson’s violent death lingers over Colac and Victoria Police