Spanish flu epidemic of 1918-1919: How Australia fared better than most

Public events cancelled. People wearing masks. A pervading fear of infection and death. The Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-19 bears many eerie similarities to today’s Australia.

Health

Don't miss out on the headlines from Health. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Walt Disney and Greta Garbo both caught it. Donald Trump’s grandfather Frederick Trump died from it. The Spanish flu outbreak of 1918-1919 killed somewhere between 50 and 100 million people across the globe, dwarfing the death toll from the ‘Great War’ it sprang from, and transforming an already shell-shocked world in ways that few saw coming.

Such was the impact of the virus, average life expectancy in the US dropped by an entire decade because of it, says Melbourne based historian Mary Sheehan, who is researching a PhD thesis on the outbreak.

Unlike COVID-19, Spanish flu had the most deadly effect on adults in their prime, mainly those between the ages of 20 and 40. The first reported cases were soldiers on the Western Front in April 1918.

The Australia hit by Spanish flu in January 1919 was a radically different place to the nation we know today. Antibiotics were yet to be developed. There was no internet pumping out minute-by-minute news headlines; no social media to stir fears. International travel was by ship. The (all male) federal parliament sat in Melbourne.

The country was not spared. Some 15,000 people are estimated to have died from what they mainly referred to at the time as ‘pneumonic influenza’, although the exact number is far from certain. Many deaths would have been ascribed to other causes such as heart failure. The death toll in some Aboriginal communities was reportedly as high as 50 per cent.

And yet: Australia did not cop it as bad as some.

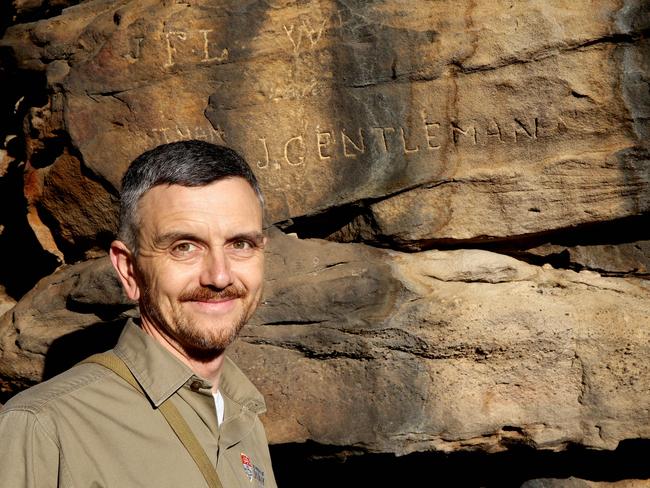

Dr Peter Hobbins, Adjunct Fellow in History at the University of Sydney, says the disease tore a swath through New Zealand, killing an estimated 2 per cent of the population, whereas the death rate in Australia was about half of one per cent.

The difference between the two countries was in their approach to quarantine. Tight controls in Australia delayed the virus coming ashore and made a huge difference to the scale and severity of the eventual epidemic.

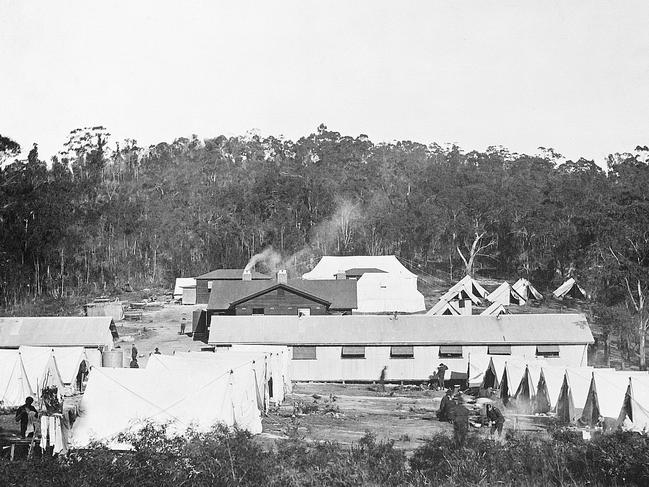

“By October 1918, when the first ships carrying cases of pneumonic influenza arrived in Australian quarantine stations, we were very aware of how dangerous it was, and we had a very rigid quarantine system to keep those ships under observation until everybody on board was all clear,” Dr Hobbins says. “That gave Australian health authorities time to prepare for what would happen should the disease come ashore.”

Warnings poured in from around the world, especially from the US and South Africa, where port cities like Philadelphia and Cape Town suffered massive fatalities.

“We were well aware of what was going on around the world, both through the media and also through military medical channels and high level government channels, which were sending reports of infected Australian soldiers and nurses, but also how it was affecting other armies and populations around the world,” says Dr Hobbins.

The messages coming from across the Tasman proved to be especially crucial.

“(New Zealand) sent a lot of urgent messages across, saying once it gets in, you won’t be able to control it; be prepared; get all your measures in place,” Dr Hobbins says.

Quarantine was eventually breached in January 1919 – probably because somebody deliberately circumvented it, says Dr Hobbins.

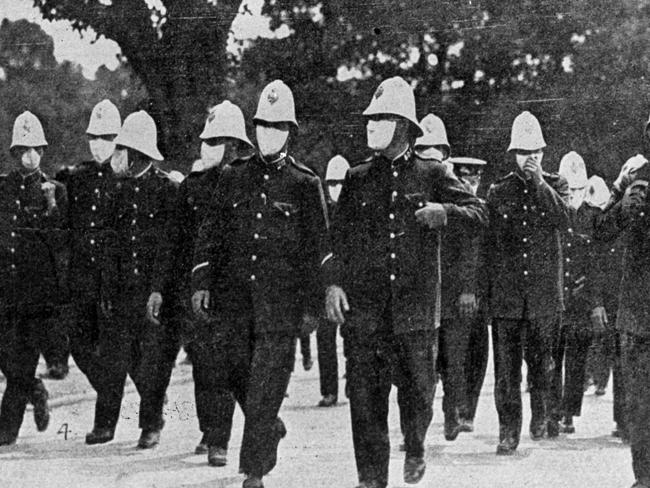

The measures put in place to deal with the crisis were drastic, although they varied from state to state. Schools did not open until March. Theatres, sporting fixtures and even libraries were shut down and mass events such as Brisbane’s “Ekka” were cancelled.

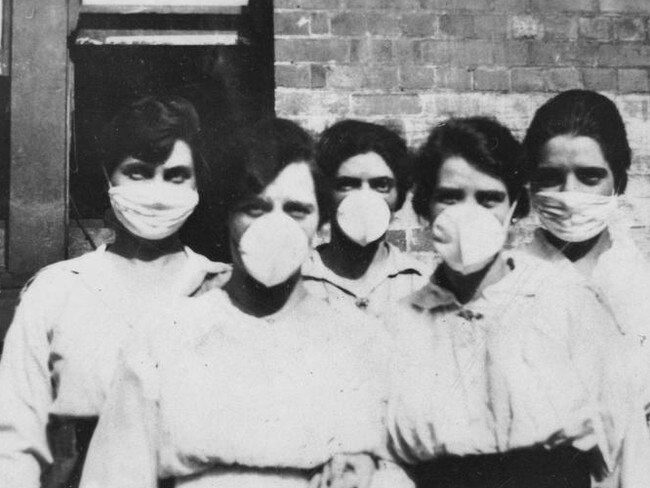

In NSW, the wearing of masks in public was mandated, with a government decree stating that those who refused to wear facial coverings were “showing their indifference … for the lives of others”.

In Victoria, pubs were closed, only to be reopened, after mass protests, on the proviso that they had no more than 20 people inside.

The impact on workplaces was immense. Dr Hobbins says a survey of several hundred companies in NSW at the end of 1919 revealed about 36 per cent of employees had needed to take time off work for influenza that year.

In Melbourne, says Mary Sheehan, “the police were seriously affected [by absences], and many people were taking advantage of the lesser police presence”.

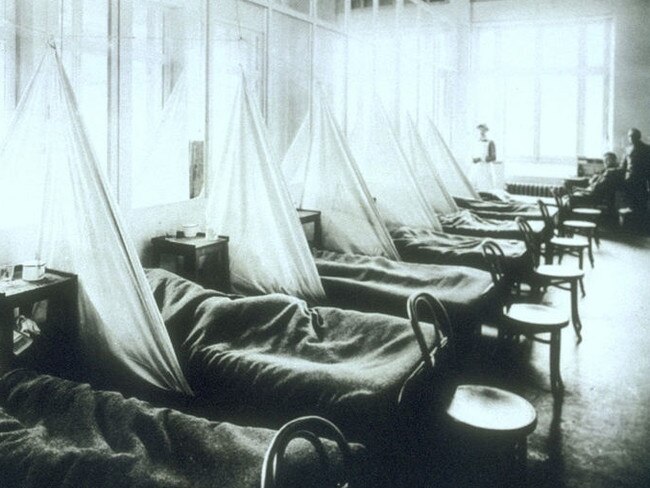

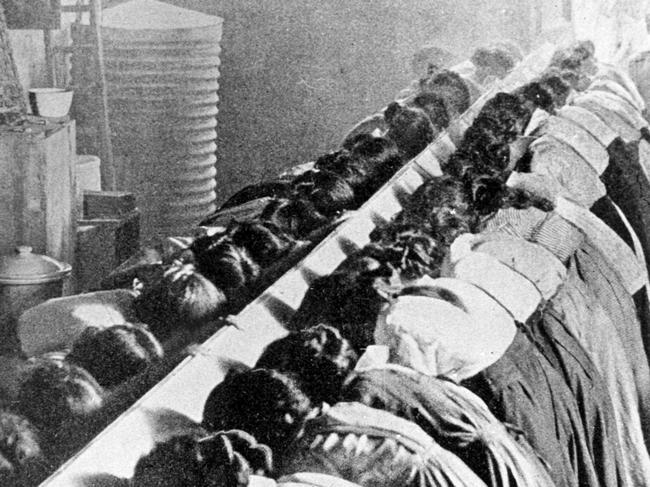

Quarantine stations were established throughout the country, with a major camp near Adelaide University reportedly having a markedly convivial, picnic atmosphere.

But for those who got sick, treatment was grim. Little could be done for them except good nursing care and keeping them hydrated to avert fever.

Health authorities in Melbourne made a critical early mistake in shutting 15 makeshift community hospitals in March 1919, believing that the virus was petering out, Ms Sheehan says.

“There were three waves of the virus in Melbourne. The first, which was a little bit milder, started in January but it began to peter out in March.

“The government thought it was all over. They closed a lot of the emergency hospitals and no longer required mandatory reporting of cases, but then it really ramped up again in April, and that really tested the whole health system,” she says.

“There were also limited numbers of doctors and nurses because many were still overseas, so there were huge challenges.”

Related News:

Tasmania announces border control measures

The celebrities with coronavirus

Supermarkets overwhelmed by panic shopping

Differences in approach eventually led the states to shut their borders for the first time since Federation.

“In November 1918 the Commonwealth and the states agreed that they wouldn’t close the borders, and that the Commonwealth would have responsibility for all quarantine decisions,” says Dr Hobbins.

“Unfortunately that agreement didn’t last long. By mid January in 1919 there were cases in Victoria but they weren’t definitively diagnosed as pneumonic influenza, because of course normal flu was still doing the rounds as well.

“So Victoria didn’t announce that they were infected, but several cases travelled from Melbourne to Sydney … and so in response New South Wales closed the border with Victoria and broke the agreement with the Commonwealth. Then they also closed the border with Queensland and South Australia, so there was a bit of tit for tat closing of borders. There were internal quarantines along the Murray River and along the Queensland border, and they operated through a lot of 1919.”

The crisis may have breathed new life into old suspicions between the states, but it seems most ordinary Australians resisted the temptation to break bad.

Ms Sheehan says while there were some reports of disturbances at inoculation sites, where people rushed to get to the front of the line, most people were well-behaved, and there were many examples of community-mindedness on show.

“There was incredible spirit,” she says. “These groups had formed during the war, so you had women’s groups who would provide food for their local emergency hospital. People would put ’SOS’ signs in their front door if they needed help, and women would go in and nurse them and clean and wash. It was really very impressive.”

And there was no panic buying of grocery staples, she adds.

“People didn’t have the money or resources to panic buy; I haven’t come across any evidence of that,” she says. “People were living hand to mouth, many of them, particularly after the privations of the war. They had stopped wage increases, but that didn’t stop price increases on goods, so that made it even harder for people to stockpile.”

The virus “became progressively less fatal as it moved across to South Australia and Western Australia and into Tasmania,” Dr Hobbins says, but it hastened some significant changes in how the country was run.

“The Commonwealth Department of Health was established in 1921, and that is not an accident,” he says. Previously, health services had been provided through local governments, churches and volunteer organisations, but the arrival of Spanish flu “led to political pressure and popular support for a more overarching system of Commonwealth health provision.”

The Spanish flu crisis has been underrated for the role it played in helping shape Australia’s national character, Dr Hobbins believes.

“The community had spent four years fighting this foreign war, and then in the fifth year, in 1919, the fighting was over but there was a new war, except it was on Australian soil and it was the same sorts of people who pulled together yet again to provide welfare and community support,” he says.

“Many talk about how Australia was born in the First World War … but I think that the way local communities, families, church groups, voluntary organisations and local councils pulled together in 1919 in the face of this overwhelming crisis, also confirmed a newer sense of national community, and that went right down to the levels of individual neighbourhoods.”

Mary Sheehan says it is a curious thing that the Spanish flu became a forgotten part of our history.

“I don’t really have any clear reasons for it,” she says. “It was retained in the memories of individual families who had known someone who died, but it’s never been acknowledged in Australia, even though it was devastating.”

Originally published as Spanish flu epidemic of 1918-1919: How Australia fared better than most