Book extract: The Morning They Came For Us

WHEN Nada was taken from her home she was tortured until she broke. Then terrible things happened - things she can’t say out loud.

Books & Magazines

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books & Magazines. Followed categories will be added to My News.

SYRIA, JUNE 2012

WHILE I was lying on the floor, they stood over me, kicking me in the teeth and punching me and using their hands and feet. One man put his military boot in my mouth.

I lay there hiding my face as they kicked and thought: “They are using my body to practise their judo moves.”

And the entire time they were beating me, they kept saying: “You want freedom? Here’s your freedom!” Every time they said freedom, they kicked or punched harder.

Then suddenly the mood changed. It got darker. They started saying if I did not talk, they would rape me.

The morning they came for her, Nada was still in her pyjamas. The air was cool from the night before, so she judged it to be about 6am. She heard the servant of the mosque call out for morning prayer, and heard her father — a welder who always got up in the early light — rising to pray.

For a moment, just when Nada opened her eyes, she tried to forget what the day might bring, imagining that her life was normal, as it had always been — before 2011, before the uprising.

Two days day earlier, Nada had received a strange phone call. The number did not register on her caller ID. She stared at the monitor on her phone, then pressed the green button to accept the call.

“It’s me,” he said, “I’m in prison.”

She recognised the voice. It was a close friend, a colleague. Someone who also called himself an activist like her. He had been picked up by Syrian state security and taken to the Central Prison in Latakia, Syria.

“Why are you calling me?” Nada asked, sitting down on the floor, the phone pressed to her ear. But she knew the answer, feeling her stomach turn over in fear.

“Can you get here right away?” he begged. “Can you come to the police station? They want to talk to you, too.”

It was a signal they had practised since the war started.

It meant the police had caught him. He was probably being beaten, and was told to hand over the names of any fellow activists who were working against the Assad regime. Maybe they had smashed the bottom of his feet with a club, or attached his testicles to wires and turned on the electricity; maybe they had held his head under water until he thought his lungs would burst. Nada tried not to think of him, vulnerable, exposed, in pain. Crying.

Whatever had happened, he had probably cracked and given up Nada’s name. But he had done her a favour by calling: it meant she had time to run.

She pressed the red button, ended the call, and drew herself into a tight small ball. She had nowhere to run. All she could do was wait.

***

The lowest depth that a human being can reach is to perform or to receive torture. The goal of the torturer is to inflict horrific pain and dehumanise another being. The act not only destroys both parties’ souls — the victim’s and the perpetrator’s — but also the very fabric of a society. By subjecting men or women to enforced violence, sexual violation, or worse, you transform them into something subhuman.

How does someone return to the human race after such brutalisation?

By early 2012, reports began emerging of mass rape in Syria, on both sides of the conflict. In January, the International Rescue Committee’s report included surveys from Syrian refugees in Lebanon and Jordan identifying rape as ‘the primary reason their families fled the country’.

The number two in charge at the UN’s refugee agency, UNHCR, using the IRC report, claimed: ‘Syria is increasingly marked by rape and sexual violence.’

While the crimes have been cited by both sides of the conflict, they seem to be perpetrated predominantly by President Bashar al-Assad’s men, largely paramilitary agents known as Shabiha, or ‘ghosts’.

Although Assad’s own government troops were not always the perpetrators, the Shabiha did most of the dirty work when it came to sexual violence. Their tactics were largely to incite fear within communities — to enter towns or villages after the government troops had been fighting nearby, and spread the word that they would rape the women — daughters, mothers, cousins and nieces.

Frightened, people would run, leaving scorched earth behind. It’s a convenient way to ethnically cleanse an entire region. Fear can be generated so easily.

Sexual violence was not reported to be only against women either. There are many accounts of male rape, particularly in detention. Although prisons and detention centres were usually the most susceptible places for the crime to occur, it happened at checkpoints and when houses were being ‘cleansed’ as well.

Following the IRC report, videos began appearing on YouTube, as well as on Twitter and blogs, translating confessions of various captured Shabiha. The danger of such confessions is that some — such as that of the admitted rapist below — could not be verified as not having been given under great duress.

But the testimony given by a captured Shabiha is still chilling documentation.

Question: How long have you been with the security forces?

Response: Since the beginning of the revolution.

Question: What is your aim?

Response: To quash the revolution.

Question: And what else?

Response: We were induced by a certain amount of money.

Question: How much?

Response: 15,000 Syrian pounds. ($AU88)

Question: Weekly? Monthly?

Response: Monthly.

Question: Do you go out to carry out raids?

Response: I go out on a security purpose.

Question: On a security purpose?

Response: Indeed, on a security purpose.

Question: With the army?

Response: Yes, and we raid the houses on the basis we are the security forces.

Question: Security forces?

Response: Indeed. We enter the houses to search. If there are men we push them out of the houses for a few hours. We take all the money and jewels we find. And if there are women, we rape them.

Question: How many women did you rape?

Response: Seven cases of rape.

Question: Seven?

Response: Indeed.

Question: Where did these rapes happen?

Response: Some at the village Al Fawl. First cases at the school, we raped them for six continuous hours. Then we entered another house as security forces on the ground that there are terrorists inside. We entered the house, we have tied the man, stolen jewels and money, and we raped women. One of them is from Knissat Bani Az. And we were four to rape her (me and three shabiha) and she committed suicide following her rape. The other case is a girl, we entered to search her house as security forces and we have stolen money and raped her. And there is another rape in Damascus. We entered her house on the ground we are security forces elements. We entered the house and raped the girl.

***

Nada’s time had come.

The police (or perhaps the secret service or intelligence, she was not sure who they were) entered the room, sat down and looked at her as though she were a dog. One said abruptly: “Talk or we will strip you!”

Nada, however, remained huddled on the floor, shaking with terror. “I was like one of those little dogs, you know the kind that shake and shake and cannot stop shaking?”

She had never thought this would happen to her, never considered the potential consequences if she got caught working with the opposition. “I just did it. I did not think — maybe I did not let myself think — of what could happen.”

Still, Nada did not cry, at least not at first. She just lay on the ground wishing she were dead.

Eight months and three days is a horrifically long time to be held captive and tortured. And the pain wasn’t just physical.

Perhaps the worst part was that her jailers delighted in telling her that her family had been notified she was dead.

In fact, Nada spent her days and nights in a dirty cell not far from her childhood home, but the people she loved most in the world were grieving for her. They believed her body was no longer of this earth. She felt invisible. She felt alone.

The psychological torture was more terrifying than the physical abuse.

“To think that the outside world, the people that love you think you are dead when in fact you are alive …”

A small, dark cell became Nada’s home for eight months.

Nada’s cell was not even big enough for her already small frame to stretch out in; she remained curled up. The jeans she wore throughout the entire ordeal are still creased in the areas of her body which she was unable to move.

“I kept them,” she says. “To remember what they did to me.”

In one corner of the cell, there was a hole — an Arabic toilet — and a water tap. “I kept the water running all the time because I was afraid of rats coming up the drainpipe and biting me.” She could not sleep, and when she did, she dreamt of those same rats covering her body. She would wake up crying and screaming, clutching her body to protect herself from the imaginary rodents.

Other men and women were kept in the cells next to her own. She did not know who they were, but they too would scream out, crying, pleading for mercy, for an end to the torture. Some cried for their mothers.

“This was part of my torture,” she says.” To hear other people begging, and to know they were coming for me next. When they would stop in front of my door and turn the key — my heart would stop.”

She tried to keep track of time, but it was impossible as her body wasted away. She imagined herself disappearing.

Her family too. She had no news of them, nor of her friends, nor of her other captured colleagues. They told her that other activists had betrayed her, that Assad had won the war, and that the opposition was dead. “I sunk into a dark place.”

When she asked for water, they would bring a male prisoner, make him urinate into a bottle, and try to force her to drink it. When she spat it out, they would throw it back in her face. The male prisoner, equally humiliated, would avoid her eyes.

“I remember every single one of their faces,” she says bitterly of her tormentors, of that memory. “I will look for them. I AM looking for them.”

The stripping led to beatings. The beatings led to further abuse.

She was relentlessly interrogated for names, dates and occasions where she met her fellow Syrian Youth Union colleagues.

There was always at least one interrogator, sometimes more. She would sit; they would circle her like wolves.

She was continually threatened with rape.

“They would say ‘Talk or we will strip you’,” she says, covering her eyes with the swipe of a hand. “That was their line, their threat.”

One day, when she was not telling them what they wanted to hear, they brought her to an all-male cell where the prisoners were in their underwear.

The men stared at her lustfully. She was one of them, but they were men, and they had been locked up a long time.

“It was horrible,” she says. “Humiliating. They told me they would leave me with these hungry men and they would take care of me.” She felt like a rabbit surrounded by wolves.

“I am a conservative Muslim woman, I thought I was being given to these men for them to rape me,” she said. “And so I started screaming. I think I screamed for three hours. Until my throat was stripped raw. They wanted to break me. And they did. Finally, I said, ‘Okay, I will tell you the truth’.”

She said she talked. She told them things. But what she told them was not enough. After several hours, they moved her — the first of many moves — and brought her to a place that she calls “the horror room”. The room was only as wide as “a man’s body”. They tied her hands to an iron bar behind her back.

Then a man entered with a whip. “Every time I said something he did not like,” she says, beginning to break into sobs, “he whipped me.”

Her bloodied and bruised body was then handed over to another interrogator, who was told, “Okay, now really take care of her.”

“Now the real beatings began,” she says sombrely, “and the terrible things.”

***

For more than four years, I roamed refugee camps, safe houses, cities and towns in Lebanon, Egypt, Turkey, Jordan, Syria, Kurdistan and Iraq, talking to women who had been raped during the war.

Initially I did it as a journalist and analyst; later I worked for the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) working on reports about Syrian women who were left alone owing to the war, and were susceptible to sexual prey.

When I met Nada in a safe house in southern Turkey, she had been out of prison for some months. But she still had the reflexes of a prisoner, of someone huddling in a corner, protecting her face and her body from blows.

Sudden movements made her jump; she would frequently get lost in her thoughts, and stay silent for several minutes, or well up with tears.

She was minuscule in size, thinner than when she had entered prison, which made it hard for me to believe that anyone could beat her with a stick or a whip.

She looked as though she would break in two if you touched her. Her body was the size of a 12-year-old: no breasts, no hips, shoulders hardly wide enough to carry her frame. She wore a lavender hijab and a tight red sweater. The childish clash of colours seemed to emphasise how young she looked.

When we first met, she cowered when I touched her hand in greeting. She seemed broken, vulnerable. She would not use the word rape. She told her story in staccato. But after a while of sitting quietly, her face changed into a myriad of emotions — sadness, pain, then the heavy flood of memory, and finally revulsion. She told of the day they brought in a male prisoner and forced her to watch him being sodomised. As she talks, her voice deadened, she opens and closes her hand mechanically, clutching at the straps of her backpack. She starts to cry. It very quickly turns to a raw sobbing.

“The things I saw ... the things I saw ...” she spits out.

“It is unbearable to explain what I saw ... I cannot forget … I saw ... another prisoner being raped ... a man being raped. I heard it ... I saw it ... Do you know what it’s like to hear a man cry?”

She abruptly gets up from the chair where she is sitting, claps a hand over her mouth, and runs into a nearby bathroom. She turns on the tap and begins to vomit.

A friend, who is with her, is also close to tears.

“Yes, Nada was raped,” she says. “But she can never admit it, even to herself.”

Her friend goes to console her. She comes back. “She cannot even say the word aloud. When she talks of others and what they endured,” her friend says, “she is talking about what happened to her.”

There are no words to say to her, no more details to extract.

What has happened to Nada cannot be undone. What she has seen and heard cannot be forgotten. It cannot be erased.

A few days later, I offered Nada and a friend a ride in my car to a class in Antakya. They were studying English together, taking a course that Nada hopes will eventually get her a job, and maybe a chance at a new life. When her friend talks about this, Nada offers a fleeting smile, and looks, if only for a moment, like any other young woman her age setting out into life — confident, happy, free.

Then something crosses her mind, and her eyes go grey and dead once again.

“I changed a lot when I was in prison,” she says quietly.

Then she smiles. “But you know, even there, I was the revolutionary.”

In between beatings and interrogation sessions, she confronted her jailers. She chastised them for small things, for prisoners’ rights. It gave her a feeling of having some control.

“I made them get plates for the other prisoners!” she says proudly. “I made them realise we are not just dogs to be kicked and used, but people. I made them put plastic over the broken windows.” She looks faintly triumphant. “Before we had nothing, then we got plates!”

Small victories for a broken spirit.

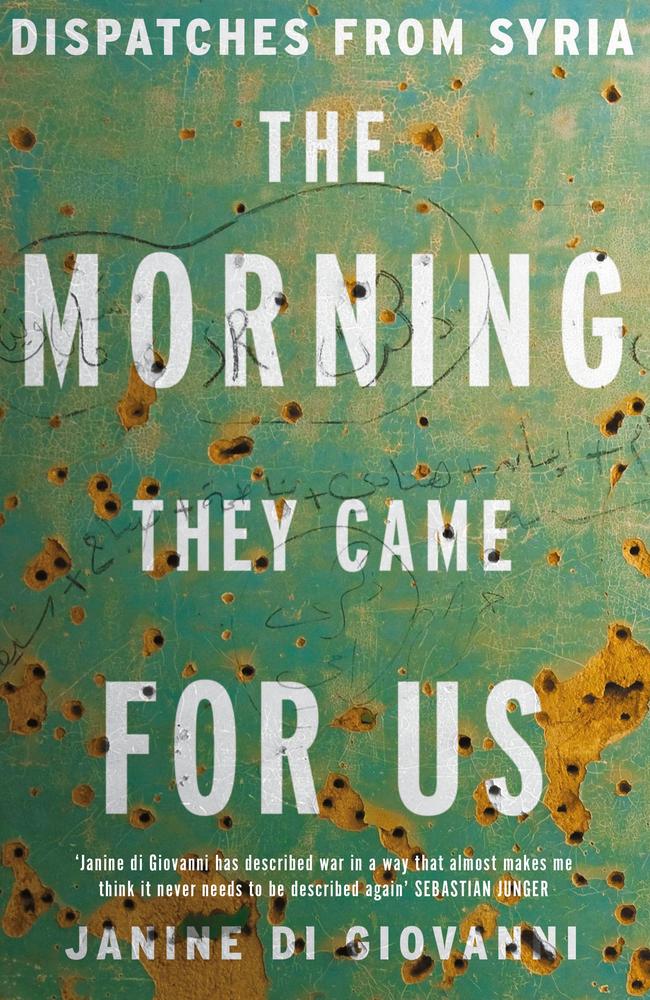

This is an edited extract from The Morning They Came For Us by Janine Di Giovanni, published by Bloomsbury, out now. RRP: $27.99.

Originally published as Book extract: The Morning They Came For Us