Book extract: Bomb disposal expert’s finest hour

KIM Hughes has seen horrors we can’t comprehend but one day stands out for Britain’s most highly decorated bomb disposal operator.

Books & Magazines

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books & Magazines. Followed categories will be added to My News.

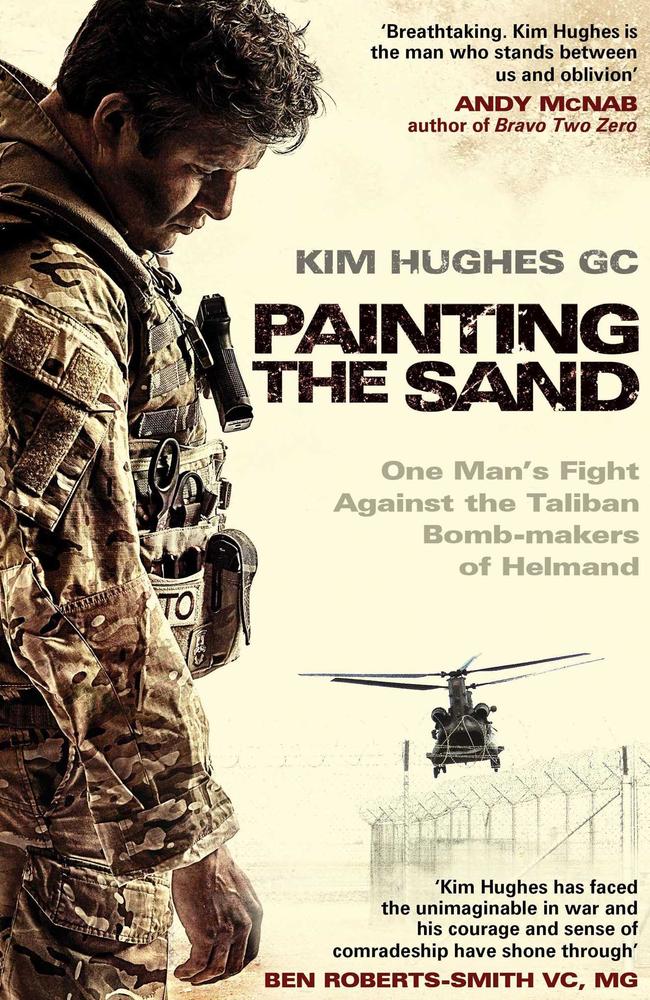

GROWING up, Kim Hughes was the “fat kid with the girl’s name who could barely read or write”. Today, he’s the most highly decorated bomb disposal operator in the British Armed Forces.

During his six month tour of Afghanistan in 2009 he defused 119 improvised explosive devices and saved countless lives. But one particularly devastating day stands out.

In this extract from his book Painting The Sand, he explains what happened.

***

SOMEONE once said when you’re in a minefield tread carefully and try and get to the other side. It was sound advice and something that flashed across my mind as I began formulating my plan.

Dead, dying and wounded soldiers were trapped in an area of hell about a third of the size of a football pitch. It was always advisable to assume that where there was one IED there could be two and if there were two, then ...

“Fully (Lance Corporal James Fullarton) was lead search man,” the sergeant said, breathing heavily and breaking my concentration. “He stepped on an IED. Both legs gone above the knee. We tied tourniquets around what was left of his legs and got him onto a stretcher. As we started the evacuation, one of the two stretcher-bearers triggered another IED. They are both Fusiliers and we think they are dead.”

As he spoke the haunting sound of the Muslim call to prayer echoed around the valley. The sound of the explosions would have already alerted the Taliban. There was time to get the dead and injured out but not much.

“That’s one of the lads,” the sergeant continued, pointing at a soldier who was clearly dead. The young Fusilier had lost both legs and an arm and the force of the blast had bent what was left of his body in half.

“We think the other stretcher-bearer was blown into the reeds.” He pointed at a piece of ground about twenty metres away.

“We haven’t been able to make any contact with him and no one has been any further forward than this since the second blast.”

The sergeant’s eyes were wide and empty. His hands were trembling and his white, mournful face was spotted with dirt and blood.

“We have three more casualties,” he said. “The medic who has sustained a bad leg injury and two other soldiers with unknown injuries, but they’re conscious and don’t appear critical. No one is moving. The sergeant major has ordered everyone to stay still.”

The brief took no more than thirty seconds. It was a shocking scene but I felt no real emotion, just a sense of appalling waste.

Fully’s condition was critical. Still alive, but only just. “We need to get him out of here ASAP!” the medic shouted.

“Fully, Fully. Can you hear me? We’ve got you, mate. We are going to lift you out of here and take you back to Bastion.” Fully was barely conscious. He was slipping away.

More soldiers arrived and Fully was placed on a stretcher for a second time before being carried out of the killing area to the HLS for a rendezvous with the MERT.

Paddy had by now made his way to the injured medic. He was trying to keep her calm and pleading with her not to move when Sapper “Foz” Foster, who was clearing the ground around Paddy, shouted: “Kim, we’ve got another IED!” He was pointing at the ground near where Paddy was kneeling over the casualty.

“Right, come back to me. Then clear me to the device and I’ll deal with it,” I said, ensuring that my voice sounded calm.

The bomb, buried in the gravelly bottom of the dried riverbed, was less than an arm’s length from Paddy.

He was hunched over the casualty, sitting on his ankles and tying a field dressing around a horrendous, gaping leg wound. When I reached him, he looked up at me as though saying: What am I supposed to do, I’m not trained for this.”

The female medic was in a bad way. The muscle hung from her shinbone and the bottom half of her leg was barely attached. She had lost a lot of blood and was going into shock. “You’re doing fine, mate. Stabilise the wound so we can get her out. Do what you can,” I said before getting to work on the IED.

It was a Category A scenario — meaning there was a grave and immediate threat to life. There was no time to conduct the usual EOD procedures of clearing devices remotely. The rules had to be ignored.

I had to conduct what’s called a “manual action” — get inside the bomb, cut the wires and pray it wasn’t booby trapped. It was a risk but a calculated one. I had trained for this very situation.

Back in the comfort of the Felix Centre you wished for the chance of dealing with a Cat A scenario; now here it was as real as the sun in the sky.

I dropped down, lying flat on my stomach and slowly ran my Hoodlum — a small hand- held metal detector — over the ground and almost instantly got a metal hit. A high- metal pressure plate buried just below the surface of the dried riverbed.

The injured medic’s screams had become a whimper. She was slipping away. I looked up at Paddy and he mouthed the words “Not good”.

I searched around for part of the device, a wire that I could attack. It didn’t take long. I allowed myself the briefest of smiles as I uncovered a length of white twin-flex wire. I pulled my snips out from the front of my body armour, held my breath and carefully cut one of the wires.

There was something reassuring about the snip sound and I felt totally in control. I quickly taped both ends of the exposed wire. By cutting the wires I had effectively put a ‘switch’ into the system, making it safer than it had been a few minutes earlier.

Digging deeper, I found a pressure cooker filled with explosives and pieces of scrap metal, whatever Terry could throw into the mix. The bomb, although still a threat, was now safe and the evacuation of the injured medic began.

Just as I began to feel that we were getting a grip on the situation one of the searchers announced that he’d found another IED. “Christ. Right, mark and avoid. I’ll deal with it.”

Over the next fifteen minutes, four more IEDs were found bringing the total to seven. The size and design of the main charges varied. Five of the charges were contained in pressure cookers and two were in plastic containers.

The bombs were all impregnated with pieces of scrap iron and steel, such as nails, nuts and bolts. They were designed to kill or at the very least cause horrendous injuries — on both counts the Taliban had succeeded. The design and layout of the minefield was quality. Someone had really done their homework and my gut told me that the Taliban’s top bomb team in Sangin must have designed the ambush.

Within thirty minutes of the first explosion the four wounded soldiers had been evacuated and we prepared to move the dead. Time was now running out and it was surprising that the Taliban hadn’t turned up to take us on.

As I surveyed the area I felt something wasn’t quite right. I’d been so focused on the mission that the obvious hadn’t occurred to me and then the penny dropped. No power packs. Pressure plates, main charges, wire and dets had all been located but no power packs. Not one. But the bombs were live. So what was going on?

I retraced my steps to the site of the earlier explosions and began to sift through the rubble in the craters. No batteries, just wires everywhere. I traced a wire to see if it was connected to a battery somewhere in the distance but discovered that the wire had been spliced onto another wire.

Initially I was baffled, then I realised that the wires from all the devices were connected to a central power line. Each device had its own main charge, pressure plate and detonator but they were all powered from a central source.

The IEDs were wired in such a way that one could explode while the others could remain intact — exactly what had happened earlier that morning.

The Taliban could arm or disarm the entire IED belt or minefield by disconnecting the battery. Once disconnected a tank could literally be driven over the pressure plate and it wouldn’t function. This gave the Taliban freedom of movement right across the wadi without fear of stepping on one of their own devices.

The minefield wasn’t something the everyday Taliban could throw together on their own. Its design required a detailed understanding of electronics as well as talent. The Taliban were getting help. But from whom? The Pakistanis? The Iranians? If anyone knew they weren’t going to tell us.

Following the casualty evacuation, the pace of events began to slow down a little. It was now time to retrieve the dead.

I stood for a second, just a few feet from one of the fallen, trying to take in what had happened, the carnage and loss. What a f**king waste.

The platoon sergeant, who’d first led us to the scene of the explosion, shouted over to me. “Kim,” he said getting my attention, “I need that lad’s dog tags.” My heart sank and Lewis’s head spun round, his eyes caught mine and his expression said it all. I stopped and paused, steeling myself for the inevitable trauma.

“Just get on with it,” I said silently and cleared a path to where he had fallen. The bomb had caused appalling injuries. What was left of his body was battered and torn beyond recognition and stripped of all dignity. His was not a soldier’s death.

“Your guys don’t need to see this. Move them back,” I told the sergeant. I dropped down so that I was kneeling by his side, grabbed his body armour and rolled his torso onto one side, holding part of his body with my legs to prevent him from rolling back.

The Rifles’ standard operating procedure stated that dog tags should be placed inside the body armour. I unzipped the pocket on the front, containing the ballistic plate, retrieved his tags and threw them over to the sergeant. I breathed a sigh of relief and prepared to stand when the sergeant said: “Hang on, Kim, they’ve got to stay with the body. I needed his number for ID purposes so that I can confirm he was KIA.”

I lay with the dead soldier by my side, hoping that his death had been quick and painless. I thought of home, my son and vowed at that moment that I would survive this shithole.

After what seemed like an age, the sergeant, who had taken a note of the soldier’s name and Army number, threw the tags back. I placed them back in the pocket and made sure they were secure, knowing all too well the value these have to bereaved parents back home.

Parents who within a matter of hours would have their lives blown apart and broken forever.

I was trying to do the best job I could for him and bring some dignity to his passing. I pulled my legs back and very gently rolled his body back and patted him on the shoulder as if to say, “Rest now. Your job is done.”

This is an edited extract from PAINTING THE SAND by Kim Hughes GC, published by Simon & Schuster, RRP $32.99, on sale today.

Originally published as Book extract: Bomb disposal expert’s finest hour