From ‘working for the bad guys’ to creating a magic pub: Jock Serong’s journey to Cherrywood

Jock Serong saw the worst side of corporate law from within, when he was told to “just hammer” church victims – and realised he was “working for the bad guys”.

Lawyer-turned-author Jock Serong found out quickly that the high-flying corporate legal life was not for him – but at least it provided him with some good material for his new book.

Early in his career, and between stints volunteering with the Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service and then working in the Western Desert building a native title claim with the local Martu people, he had a couple of brushes with the high-stakes, cutthroat environment where time is billed in six-minute increments and winning is absolutely everything.

When he’d graduated from university he got “sucked into the clerkship system” where aspiring lawyers cut their teeth through hard work and long hours in the hope they’ll impress the powers-that-be so they will keep them on.

“Then they keep you, so you stay on and then before you know it, the salary has got you handcuffed to them,” Serong says in a back room of Fitzroy’s The Napier, another inspiration for his seventh book, Cherrywood.

“I was in a few years of that then I threw it in and went down the coast for a couple of years.”

After his time in the Western Desert, he had six months to kill before he could undertake the Bar Readers’ Course to become a barrister, so he carpet-bombed the major firms in Melbourne saying he had his practising certificate and asking if they had any work going.

The way he tells it, one came back to him saying, “There’s a vacancy in stapling or hole-punching or something” – and there he was in 1998, performing menial tasks in the basement, when the acrimonious waterfront dispute broke out between the Maritime Union of Australia and Patrick Stevedores over productivity and union labour on Melbourne’s Webb Docks. As wharfies clashed with police on the picket lines, his firm was battling the union in the courts in a stoush that went all the way to the High Court.

“All of a sudden the firm was just in a desperate, screaming hurry to build armies of junior lawyers to fight the waterfront dispute and someone literally came running into the room and said, ‘Does anyone in this room have a practising certificate?’,” he recalls.

“The next thing I know, I’m installed in an office as one of their minions and did six months working for the bad guys in the waterfront dispute, and that was where most of the gnarliest stuff went down.”

He describes the experience as “comfortably” the worst in his 17 years practising law, which also featured a six-year career as a barrister, which he loved, followed by a stint as a solicitor in Warrnambool after he relocated to Port Fairy with his wife and their four children. He says he baulked at the privileged world view and win-at-all-costs mentality of some of his colleagues of the era – “I remember a partner at a firm talking to me about Catholic Church victims and saying the job here is to just hammer them until they give up” – and realising that “this is not how I want to conduct myself”.

“There’s also a lot of encouragement to think of yourself as a winner and to believe that you are part of the elite,” he says. “It’s bullshit – but you’re encouraged to think that way.

“It should also be said that a lot of those people are brilliant. They’re very smart. They’re very determined. They work very hard. And so they have some justification for thinking of themselves as special. But you only have to step outside for a bit to realise that there’s lots of special people out there.”

Serong says he has no regrets about his legal career, and stresses that there are plenty of good people in big firms who do good things.

He says his own transition into full time writing was initially scary, but once it became clear where his passion now was, he knew he had to have a crack before it was too late. He had a contract for his first novel and was also writing for a surfing media when he made the leap about a decade ago and hasn’t looked back.

“Gradually over time a thing that happens to lawyers is that if you’re idealistic – when you’re young and cheap, it’s much easier to work in community settings and to do things that feel altruistic,” he says. “And as you become more senior commercially, you just become more expensive and you get pulled towards forms of practice that make money. It’s an ugly equation and people who can resist it are admirable.

“So over time, I was moving towards areas of practice that didn’t light me up so much. It wasn’t that I was unhappy, it was much more that I was exploring being a writer and I was loving it. I felt like the window to do that in my life was closing rapidly and that I had to jump at some point or I was going to miss out.”

BANDS, BREW AND BONDING: JOCK’S PUB LIFE

Serong poured some of his uglier professional experiences into the character of 26-year-old lawyer Martha in Cherrywood, noting that women had it even tougher back in 1993, when the story is set. Her frustrations at the long hours, stifling culture and a particularly awful lawyer’s retreat (taken almost word for word from one Serong endured) find an outlet when she stops at a strange Fitzroy pub one night and the mysterious moving building and its inhabitants change her life.

Martha’s odd encounter was inspired by an unsettling dream Serong had – as well as his love of Peter Carey’s Oscar and Lucinda – and he intercuts the fantastical elements of her story with the tale of Thomas Wrenfeather, a rich Scottish industrialist who moves to booming Melbourne in 1916 to build a paddle steamer made from Eastern European cherrywood. Like Carey’s Booker Prize winning classic, Cherrywood also flirts with magical realism, a term Serong is happy with, even if it’s not what he set out to do.

“I just took my leave of reality at some point and if that’s magical realism and then so be it,” he says with a laugh, “but that’s certainly wasn’t an overt aim.” Rather he just wanted to let his imagination run wild in a story that didn’t have to be as meticulously researched as his acclaimed Bass Strait trilogy of Preservation (2018), The Burning Island (2020) and The Settlement (2023). “I had just come out of writing the historical trilogy that was very, very heavily researched and because it involved Aboriginal people it needed to be rigorous,” he says. “I needed to consult and that was a particular way of writing fiction that was very, very demanding of the formal things and what I wanted to do was to go back to just making up a story and deliberately really not researching it.”

As fantastical as the story may be in Cherrywood, the strangely shifting pub is firmly based in reality. Serong worked at several Fitzroy pubs while at uni in the early ’90s, but it was the charmingly homely The Napier that left the deepest impression, and knowing its dimensions and corridors intimately allowed him to build the internal scenes from memory.

“I was on the cusp between having been a student and about to become a practising lawyer, and I wasn’t nearly as enthused about that career as I should have been,” he says.

“I think I was taking leave of one version of my life and about to usher in another one and I was having a great time. It’s interesting, because there is this common trope about first novels always being autobiographical and in a sense my first novel Quota was autobiographical because it was about a disillusioned lawyer leaving Melbourne and going down the coast, but it was autobiography on the surface. This is much more deep thinking stuff. It’s not really a map of my life at all, but it is things that I have thought and experienced.”

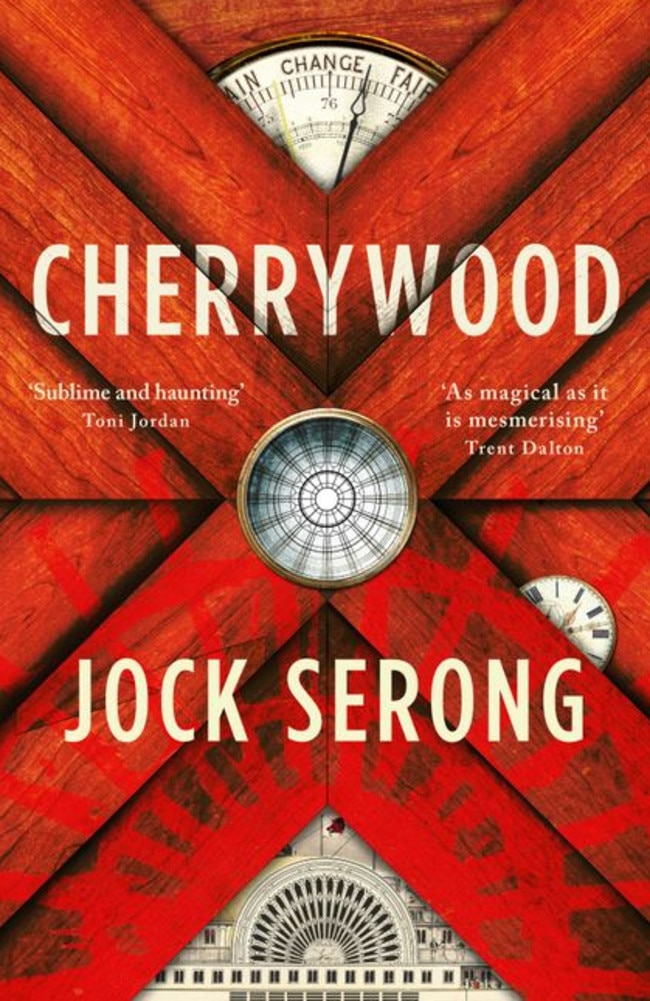

Cherrywood is out now through HarperCollins

Originally published as From ‘working for the bad guys’ to creating a magic pub: Jock Serong’s journey to Cherrywood