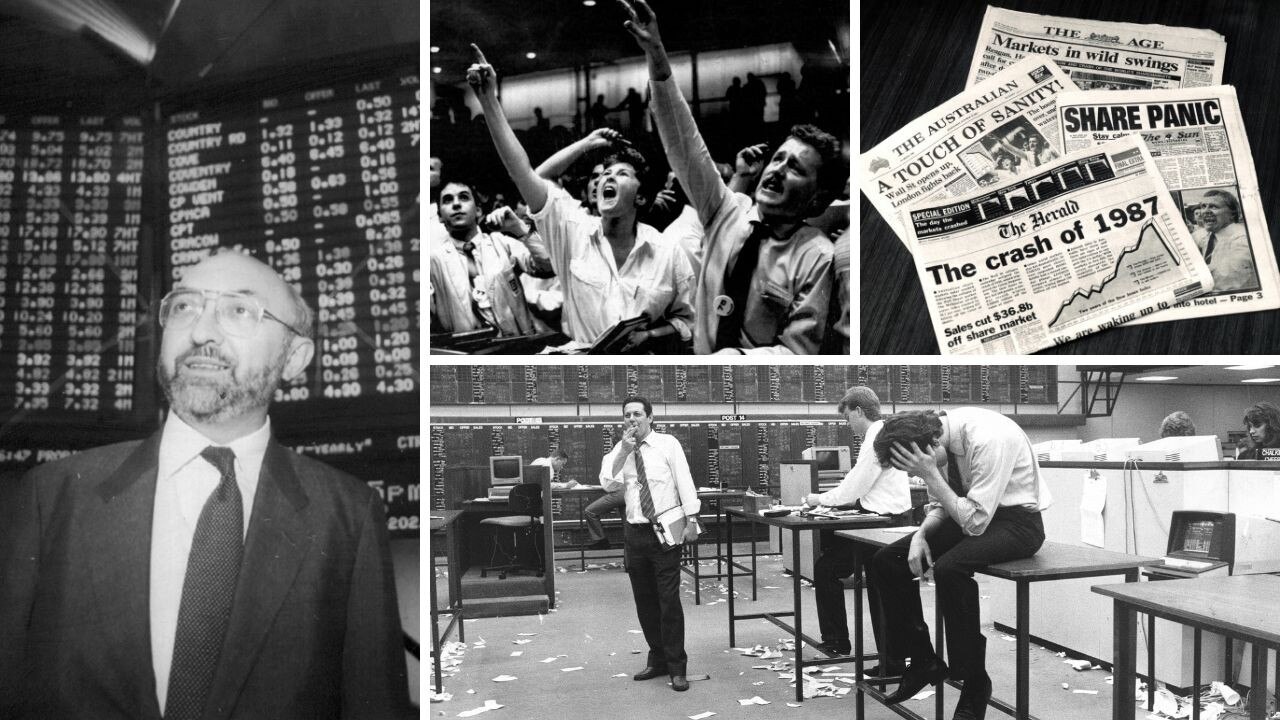

Wages now key to rates outlook

The big question facing Australia and the US is whether low inflation can come quickly and obviously enough before big wage hikes threaten to lock in a wages, prices and rates spiral.

Terry McCrann

Don't miss out on the headlines from Terry McCrann. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Two weeks ago the Fed did not deliver the interest rate ‘pivot’ investors around the world had expected – more accurately, had hoped for.

But late last week we just might have got a far more fundamental, far more powerful pivot that will play out, and far more long-lastingly, into that desired Fed pivot at its last meeting for the year just before Christmas.

These were the latest US inflation numbers. It is entirely possible, maybe even probable, that a serious and sustainable slowdown in US inflation has been ‘hiding in plain sight’.

Indeed, arguably, it’s been hiding in plain sight for a couple of months now – in a way, interestingly, which is the opposite of why the Reserve Bank didn’t see our inflation accelerating earlier this year.

Whatever, the ‘unexpectedly low inflation numbers’ for the month of October both validated the strong bounce-back on Wall St in October – in anticipation of that Fed pivot which did not arrive – and sparked a spectacular further surge.

All of which played into our market – first having dragged it up by 6 per cent through October, and then kicking it a thumping near-3 per cent higher on Friday alone.

Further, if indeed, US inflation is heading significantly and sustainably lower, this will have huge – and entirely positive – consequences for both economic policies and economic (and financial) conditions right around the world, including here in Australia.

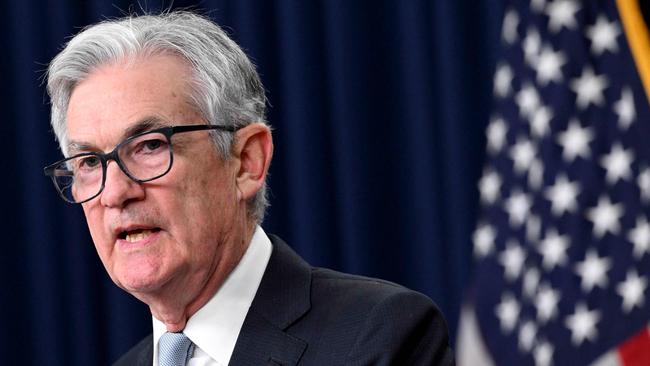

What’s been a puzzle and a remains a bit of a caution against declaring victory over (US) inflation prematurely, is that the Fed which is normally all-too eager to turn dovish on the slightest excuse, in fact, doubled down on talking tough.

Now maybe Fed head Jerome Powell was trying to psych Wall St: talk over-tough, to cement a low-inflation mindset, to more easily go really dovish in December.

We shall see. But to me the – and I stress the most recent - US inflation data was extremely, positive.

Over the four months to October headline US inflation added to just 0.9 per cent.

To stress, that’s not 0.9 per cent a month, but 0.9 per cent in total, over the four months. An annualised rate of just 3.6 per cent.

Further, critically, we also saw the same low recent inflation in the underlying, less volatile, measures that the Fed focuses on for its interest rate decision-making.

For comparison, our inflation in the three months to September was 1.8 per cent – double, in three months what the US recorded over four months.

This low number has been ‘hiding’, because all the focus has been on the ‘12 month to October’ inflation. It did come in a bit lower ‘than expected’, but it was still very high at 7.7 per cent.

The problem with this focus is it includes a ‘lot of history’ – the very high inflation in the US late last year and earlier this year after Russia attacked Ukraine.

The exact opposite happened in Australia, when the 12-month figures showed relatively subdued inflation through the December 2021 quarter - thanks to especially the (last) Victorian and NSW lockdowns.

It should have been clear that as the two biggest states came out of lockdown in that quarter, inflation really started to stir; but the RBA didn’t ‘see it’, as it was focused on the 12-month numbers and all that low-inflation 2021 lockdown history.

It became impossible ‘not to see it’ after the March quarter, and so we finally got that first rate hike in May.

The big, the humungous question – both in the US and here – is whether the low inflation can come quickly and obviously enough before we start to see inflation-chasing wage hikes.

It’s big wage hikes that would threaten to lock-in a wages-prices – and rates - spiral.

More Coverage

Originally published as Wages now key to rates outlook