How inflation could change Australia’s economic future

For many years we got to have our cake and eat it too but maybe we have entered a new reality with sustained 4-5 per cent inflation and an RBA cash rate around 4 per cent.

Terry McCrann

Don't miss out on the headlines from Terry McCrann. Followed categories will be added to My News.

We didn’t only get our first budget surplus in more than a dozen years in the financial year just ended – with treasurer Jim Chalmers beaming like a six-year old displaying his first post-tricycle bicycle, all shiny chrome, pink paint and trainer wheels.

We also saw investment returns rebound in 2022-23 – actually, seem to rebound – and which led AMP’s long-time chief economist Shane Oliver to pose the very good question: “but, is it sustainable?”.

His answer was ‘yes’, but at a lower level – with overall balanced growth super returns likely to be more like 6-7 per cent than 2022-23’s 9 per cent or so.

What struck me about 2022-23, and which is very, very relevant to both expectations and understanding of future investment returns is two things.

First, we had this year of good to very good nominal returns – depending on your perspective and your investment profile – despite interest rates rising dramatically and substantially everywhere.

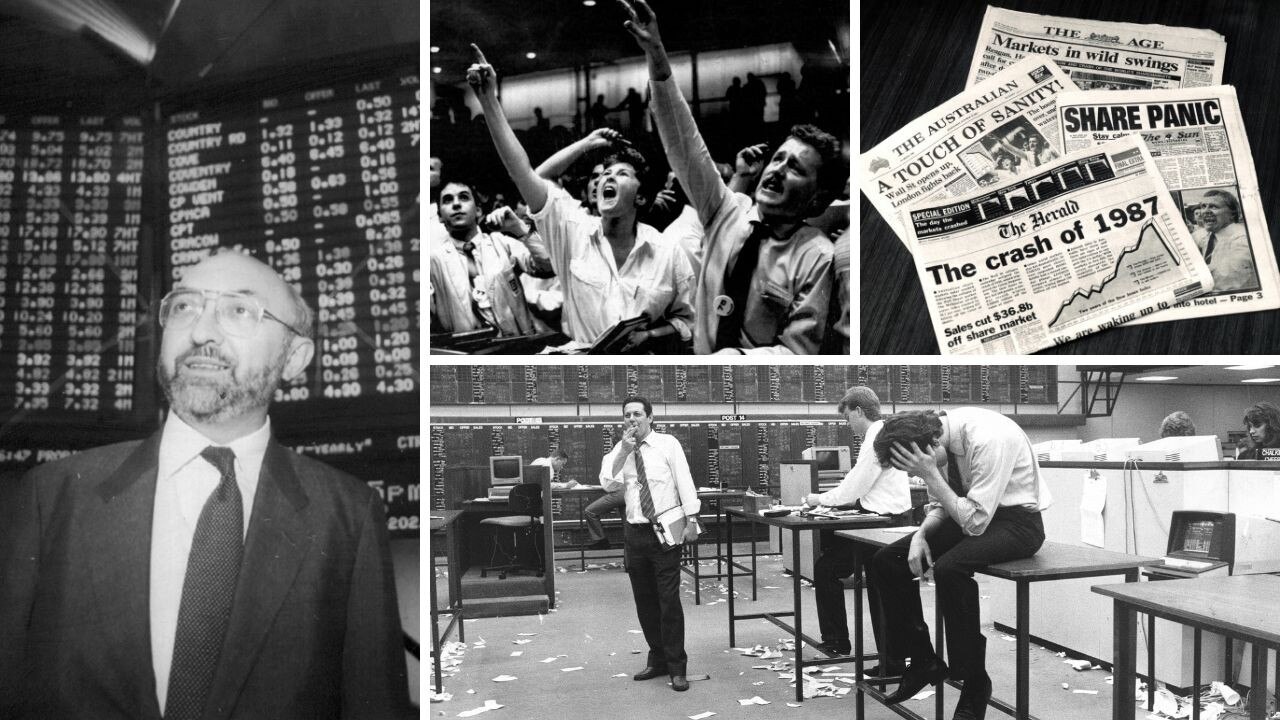

Indeed, they rose by the most and the quickest since the 1980s. In Australia’s case by a full 4 per cent.

Hang on. I was always taught that when interest rates went up, asset values – principally shares and property - went down.

Yet this did not happen; indeed the reverse happened. Food for thought?

I could spend a few columns suggesting why: the bounce-back from Covid, commodities, booming banks despite the rates, population (and super-generating employment) growth, and more.

But the more important second point, is the reason why rates went up so much and everywhere. Inflation.

For the first time, pretty much since the late-1980s, we – and by ‘we’ I mean the developed world – broke away from sustained 2-3 per cent inflation.

That does, that should, put those investment returns in a somewhat different, more sober, light.

Yes 9 per cent in nominal, cash terms. But with inflation running around 6 per cent, that makes a more subdued 3 per cent in real terms.

On one hand: that’s still pretty impressive given the rate surge.

On the other – it’s always handy to have two – hand (s), that isn’t so dramatically better than earlier, similarly inflation-adjusted, returns.

The important point is not so much the past as the future.

The analytical, and indeed coal-face investment, mindset is still locked in the world of 1993-2020.

A world of all-but never-changing 2-3 per cent inflation. A world where rates trended slowly lower. A world where property and share values rose faster than goods and services inflation.

Again, on the latter, for a complex of reasons: China, computerisation, globalisation, communication (the internet and the smart phone).

In sum we really did have our cake and get to eat it too – low inflation and ever-rising real asset values.

But maybe, just maybe, we’ve just been through the transition year to a whole new reality and a whole new investment paradigm.

There’s been – and I suggest there still is – a general assumption that after this current ‘unpleasantness’, rates and inflation will return to the levels of the 2010s.

But what if they don’t?

What if we now have sustained 4-5 per cent – or hopefully only slightly higher - inflation? And the RBA’s cash rate stays around 4 per cent?

Hmm.

Originally published as How inflation could change Australia’s economic future