Jim Chalmers channelled Peter Costello with RBA pick

Anthony Albanese and Treasurer Jim Chalmers had every right to choose the next RBA governor – but they also carry the can for that choice.

Terry McCrann

Don't miss out on the headlines from Terry McCrann. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It is important to make some basic but fundamental points before Philip Lowe formally leaves the building at the top of Martin Place in Sydney for the last time in mid-September and fades into history.

First, most critically: the government and the PM and treasurer in particular had every right and indeed both a political and policy responsibility to choose not to extend his term and to select his successor.

Yes, the governor – and board – of the RBA need to operate fully independently of the government and the treasurer in particular.

That’s, we discovered over indeed decades, and painfully, how we get the best monetary policy (interest rates) and the best outcomes for the people of Australia.

And indeed, more narrowly, the best outcomes actually politically for the incumbent government itself; although try telling that to the average, and often very ‘average’, politician.

That certainly does not guarantee we get the perfect outcome. But every example where we’ve seen a merging of the political and rate-setting, the results have been very damagingly and indeed disastrously worse.

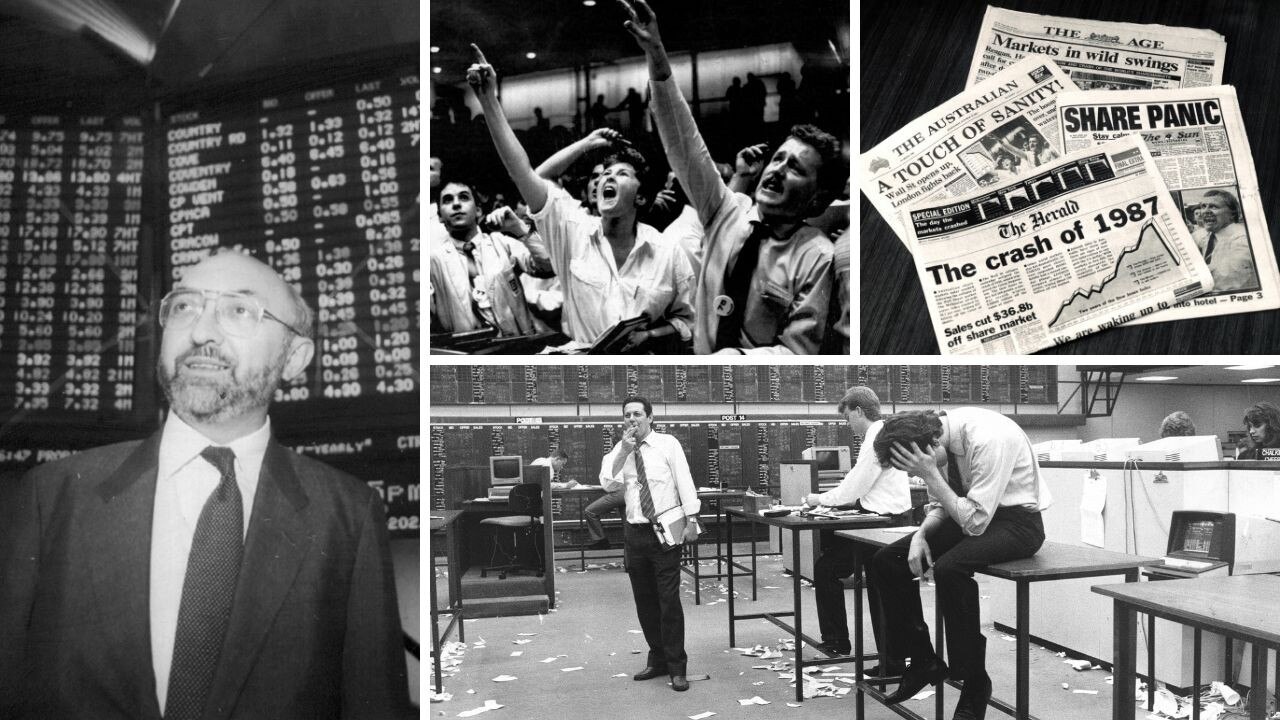

We saw this most painfully in the chaotic period at the end of the 1980s, when inflation was 7-9 per cent, and stayed there for years; home loan interest rates peaked at 18 per cent; and the jobless rate hit 11 per cent and stayed near there for years.

At the same time though, the government has the ultimate responsibility – both politically and in policy terms – for what the RBA and its governor do.

Indeed, that’s specifically written into the Reserve Bank Act. The treasurer can over-rule the board.

It’s never been done, because it’s always been considered both political and economic suicide – via the reaction in global financial markets – if it was done.

Although one young and politically ambitious treasurer came close, very close, to doing so.

More narrowly, as we can see all-too clearly right now, the government takes the rap – both the policy rap and the political rap – for what the RBA is perceived to have done or failed to.

In policy terms, what the RBA does with rates is part of the overall mix of government policy and its impact – good or bad – on the economy – and so the responsibility of government.

Politically, in 1993, the Keating government would have lost because of those high rates but for the ineptitude of then-opposition leader John Hewson.

Now, there would have been nothing wrong at all if PM and treasurer had chosen one of the top public servants, treasury head Steven Kennedy or finance head Jenny Wilkinson instead of Michele Bullock.

As indeed Paul Keating did in 1989 with his treasury head Bernie Fraser - who then proceeded to very, very effectively do his job, fully independently of his patron and his government.

When Fraser walked in the door, as governor, in 1989 inflation was 7.6 per cent. When he walked out, Lowe-like, seven years later it was 3.1 per cent.

Interestingly, Treasurer Chalmers has channelled Peter Costello and not his hero Paul Keating.

Just as Costello did in 1996, he ended up making the entirely conventional appointment of the deputy as successor, over speculation of a ‘new broom outsider

Originally published as Jim Chalmers channelled Peter Costello with RBA pick