Are we there yet? Howard Marks revisits his famous bubble.com memo

A quarter of a century after predicting the dot.com crash, influential US billionaire investor Howard Marks sees some worrying signs returning to shares.

Almost 25 years to the day, influential investor Howard Marks has revisited the memo that cemented his reputation when questioned with conviction whether the tech and internet frenzy of the time was unsustainable. Simply called bubble.com, that memo came out in January 2000.

“The memo had two things going for it: it was right, and it was right fast,” the Oaktree Capital founder recalls.

Just months after the memo was sent out to his investors, the dot.com crash hit hard.

The Wall Street collapse brought with it a dramatic end to another era of exuberance, and it crushed the valuations of tech stocks for more than a decade.

Today, Wall Street again trades at record highs after a stellar two years. With artificial intelligence driving tech names to unimaginable valuations, Marks revisits that memo.

He sees several similarities between today and 25 years ago – which should be enough to make investors sit up and take notice.

Importantly, unlike the dot.com era, Marks stops short of calling today’s market a bubble. This is consistent with his position last September during an interview with The Australian.

To spot a bubble, Marks says, you first need to know what one is. And here he is quick to emphasise a market bubble is more a state of mind over any quantitative measure. Here, the veteran investor reckons there are telltale signs when the bubble territory is reached.

Along with a rapid rise in stock prices, bubbles represent “temporary mania” fuelled by the same few ingredients. There’s “highly irrational” exuberance of markets. There’s outright adoration of companies or innovations in the belief they can’t miss – anyone remember Pets.com, eToys.com, or 360Networks?

Thirdly, there’s also the sense of FOMO for investors that they’ll get left behind. And finally, Marks says bubbles are driven by a firm belief “there’s no price too high” for certain stocks.

It’s the last point that stands out the most for Marks.

“Whenever I hear ‘there’s no price too high’ or one of its variants – a more disciplined investor might say ‘of course there’s a price that’s too high, but we’re not there yet’ – I consider it a sure sign that a bubble is brewing,” he says in his latest memo sent to Oaktree investors.

Chasing the new

Bubbles are invariably associated with new developments, whether that be technology (the internet) or innovations, such as the securitisation of mortgages leading up to the global financial crisis.

“If something’s new, meaning there is no history, then there’s nothing to temper enthusiasm. After all, it’s owned by the brightest people – and they’ve made a fortune. Who’s willing to throw a wet blanket over that party or sit out that dance?” says Marks, whose asset management firm oversees more than $US200bn ($321bn) of funds.

Marks got his formative markets experience in the late 1960s working in the equity research department at a bank which was a forerunner to today’s Citi. At the time, much of the investment was flowing into the Nifty 50 – the fastest-growing companies in the US.

“These companies were considered to be so good that nothing bad could ever happen, and there was no price too high for their stocks,” Marks says.

Of course, in the early 1970s it fell apart and as much as 90 per cent of their value was lost. Shares which had previously been trading on price-to-earnings multiples of between 60 and 90 times were suddenly valued at six to nine times.

This prompted Marks to formulate some guiding investing principles that have seen him through five decades.

It’s not what you buy, it’s what you pay for it that counts, he says. Secondly, good investing doesn’t come from buying good things but rather from buying things well.

And finally, there’s no asset so good that it can’t become overpriced and thus dangerous. The reverse is also true; there are few assets so bad that they can’t get cheap enough to be a bargain.

Then there’s the indisputable force of gravity: when stocks rise too fast – out of proportion to the growth in the underlying companies’ earnings – they’re unlikely to keep on appreciating.

Are we headed for bubble trouble into 2025?

Defying gravity

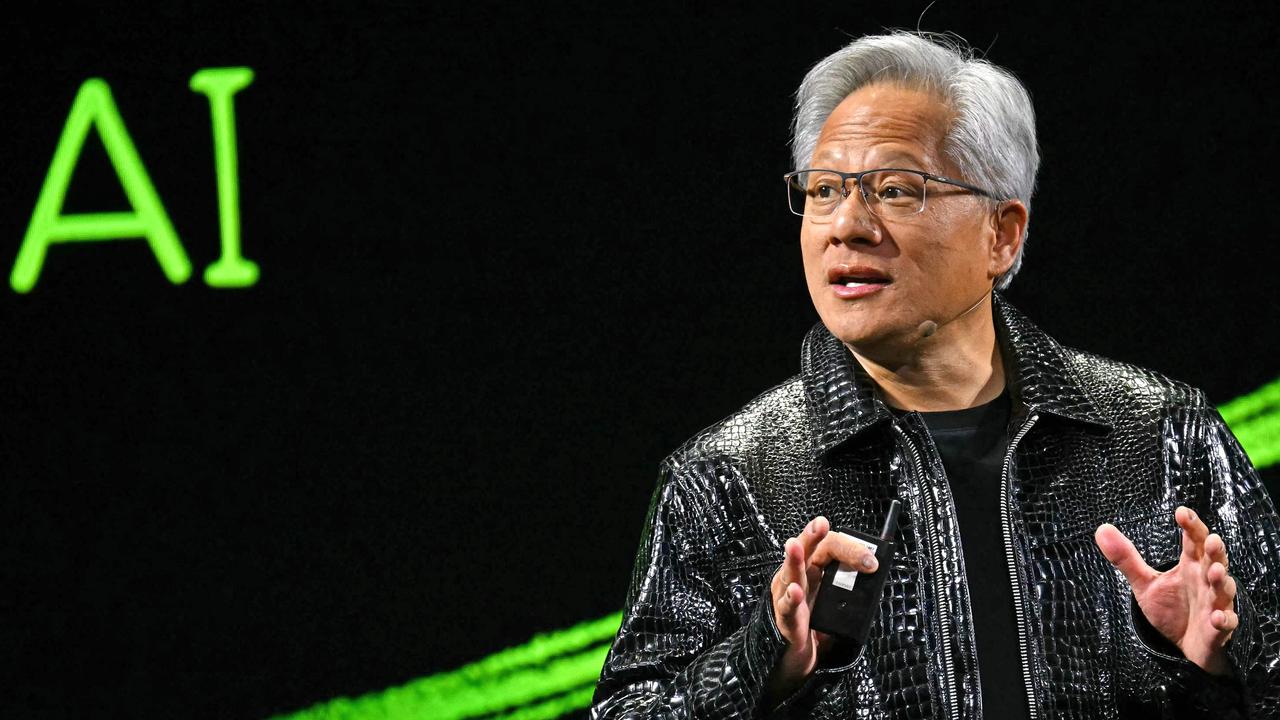

There’s been plenty of focus on the so-called Magnificent Seven stocks (Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Nvidia, Meta and Tesla) in powering most of the gains of the broad Wall Street benchmark the S&P 500.

The S&P 500 index is up more than 50 per cent over two years.

Last year, chipmaker Nvidia added more than 170 per cent alone to now be one of the world’s most valuable companies. Facebook’s Meta and Tesla each put on more than 60 per cent. Each of them are trading on average price-to-earnings ratios of more than 30 times.

Today, the Magnificent Seven collectively accounts for about 33 per cent of the total market capitalisation of the S&P 500.

One of the most worrying figures from JP Morgan Asset Management chief strategist Michael Cembalest is the last highest capitalisation share of top seven stocks of the past few decades was 22 per cent. And that was in 2000 at the peak of the dot.com bubble.

On Cembalest’s numbers, before two years ago there were only four times in the history of the S&P 500 when the index returned 20 per cent or more for two years in a row. In an ominous warning, in three of those four instances the index declined in the subsequent two-year period. The exception was 1995-98; the tech bubble delayed the inevitable until 2000 but then the index lost almost 40 per cent in three years.

On Wall Street over the past two years it’s happened for the fifth time. The S&P 500 was up 26 per cent and 25 per cent in each of the past two years. This leads to the five warning signs that Marks now sees ahead for 2025.

First: Market optimism has clearly prevailed for at least two years.

Second: The above-average valuation on the S&P 500 is currently closer to 27-times earnings than its long-term average of 16 times, and the fact that Wall Street stocks in most industrial groups sell at higher price-to-earnings multiples than stocks in the same industries in the rest of the world.

Third: Nothing but enthusiasm is being applied to the “new thing” of artificial intelligence.

Fourth: There’s the implicit presumption that the top seven companies, from Apple to Nvidia, will continue to be successful.

Fifth: The possibility that index investors have simply being momentum buying of some stocks without regard for their intrinsic value.

While not directly related to shares, bitcoin can’t be dismissed as a warning sign, Marks adds.

Gains of more than 460 per cent in two years in the asset class “doesn’t suggest an overabundance of caution”.

High price?

Several investment banks have recently come out with projected 10-year returns for the S&P 500 in the low to mid-single digits. While investors could live with those sorts of returns, Marks says, that would only be the case if stocks were to sit still for the next 10 years as the companies’ earnings rose, bringing the multiples back to earth.

But the Oaktree boss cautions that there is a worrying possibility that price-to-earnings correction is compressed into a year or two, implying a big decline in stock prices along the lines of what was seen in 2000.

“The result in that case wouldn’t be benign,” Marks says.

As mentioned from the outset, there are warning signs but Marks wouldn’t go so far as to declare today’s market a bubble.

He still sees some compelling counter arguments putting a cushion under any price revision.

These include that while the price-to-earnings ratio on the S&P 500 is high (currently around 27 times) these levels are “frothy” but “not insane”.

Importantly, he says the Magnificent Seven companies are better companies than those of the past.

They are backed by real businesses and innovation, giving some justification to their price-to-earnings ratios. They enjoy massive technological advantages. They have vast scale, dominant market shares and above-average profit margins, he says.

And they are mostly based on ideas more than metal, so the marginal cost of producing an additional unit is low, meaning their marginal profitability is unusually high.

Finally, Marks says there’s a simple measure.

No one – yet – is saying there’s “no price too high”.

When they do, that’s the surest sign the market is on borrowed time.

eric.johnston@news.com.au

Originally published as Are we there yet? Howard Marks revisits his famous bubble.com memo