Bush Summit: How Tasmania’s West Coast transformed from remote mining outpost to arts, tourism hub

In terms of population, it’s a mouse – but economically, Tasmania’s remote West Coast is a roaring lion. It’s a region poised for success and bedevilled by unique problems. We take an in-depth look at the road ahead.

Tasmania’s West Coast may be a mouse in terms of population, with an estimated 4358 residents in the area bounded by Pieman River in north, Vale River in the northeast, Cradle Mountain–Lake St Clair in the east and Macquarie Heads in the south.

However, economically, it roars like a lion, with the presence of bounteous mining riches and breathtaking national parks driving an outsized contribution to the state’s economic health and wealth.

As part of the Mercury’s Bush Summit series, we examine the opportunities available for the region to grasp, and explore the barriers in its way. We meet the people who call the place home, and the businesses that provide employment for them.

THE PEOPLE

The lion’s share of locals live in five towns: Queenstown, Zeehan, Rosebery, Strahan and Tullah. There are more males (2302) than females (2071), the median age of 45.6 years’ old is three-and-a-half years’ older than that of Australia as a whole.

Its estimated population has grown by just 140 people since 2017, but shrunk precipitously since the glory days of the early 20th-century.

The region has a higher proportion of Indigenous people (8.1 per cent) than Tasmania as a whole (5.4 per cent), and its people are less likely to have been born overseas than the rest of Tasmania.

Unemployment is higher than in the rest of Tasmania, the median wage is lower, and residents far less likely to have gone to university or completed Year 12.

They are slightly more likely to have a disability and far more likely to have a long-term health condition.

But the raw figures tell only part of the story, according to the region’s proud mayor, Shane Pitt, a lifelong resident of the West Coast.

“It’s a resilient sort of community that seems to work through the hard times. We’ve always got our heads up,” he said.

THE INDUSTRIES

Mining and tourism are the ‘big two’ industries that generate the lion’s share of the wealth and jobs for the region.

Significant mines in the region include Henty Gold Mine, north of Queenstown; Avebury Nickel Mine at Zeehan; Rosebery Mine, which yields copper, gold, lead, zinc and silver; Savage River Mine (southwest of Waratah, not technically a part of the West Coast).

The Department of State Growth calls the West Coast “one of the most mineralised places on the planet”.

According to figures compiled by council, minerals produced by the region’s mines generated $716.9m worth of sales in FY20–21. Census data indicates that the industry is the biggest employer, with 457 workers employed in the year to June 30, 2020.

Tourism, however, continues to nip at mining’s heels for the crown of the region’s most significant wealth generator and employer.

Mr Pitt said that “adventure tourism” has exploded across the region in the last few years, headlined by new mountain bike trails at Mt Owen and Silver City at Zeehan; King River’s burgeoning whitewater rafting reputation; and increasing bouldering and abseiling activity.

New investment in the sector continues, with a significant new multi-day trail planned for The Tyndalls, in conjunction with the Parks and Wildlife Service.

Mr Pitt also nominated Macquarie Harbour aquaculture and electricity generation as significant industries. According to figures collected by council, West Coast agriculture generated $41.9m in sale in FY20–21, while Granville Harbour Wind Farm produced 20 per cent of the state’s wind generation.

The Pieman River/King-Yolande hydro scheme, meanwhile, produced 25 per cent of the state’s hydropower generation.

The proposed 1500MW Whaleback Ridge Wind Farm, still in its “infancy stage,” would be another big generator of jobs and wealth, Mr Pitt said.

The arts are also becoming increasingly important to the West Coast, headlined by the continued success of biennial The Unconformity festival, founded in 2016 and hosting its next edition in October.

THE PROBLEMS

Research by the University of Tasmania, commissioned by West Coast Council, indicated that up to 31 per cent of employees in the LGA do not live locally, the highest in the state. Of that 31 per cent, 68 per cent were employed in the mining sector.

The research concluded that up to $71m worth of wealth was taken out of the region annually due to the high instance of fly-in-fly-out/drive-in-drive-out employees.

Another double-edge to the mining sword is its boom–bust nature.

After reopening in November, 13 years after it was placed into care and maintenance, the Avebury Nickel Mine at Zeehan, which employs at least 177 people, is already encountering financial difficulty.

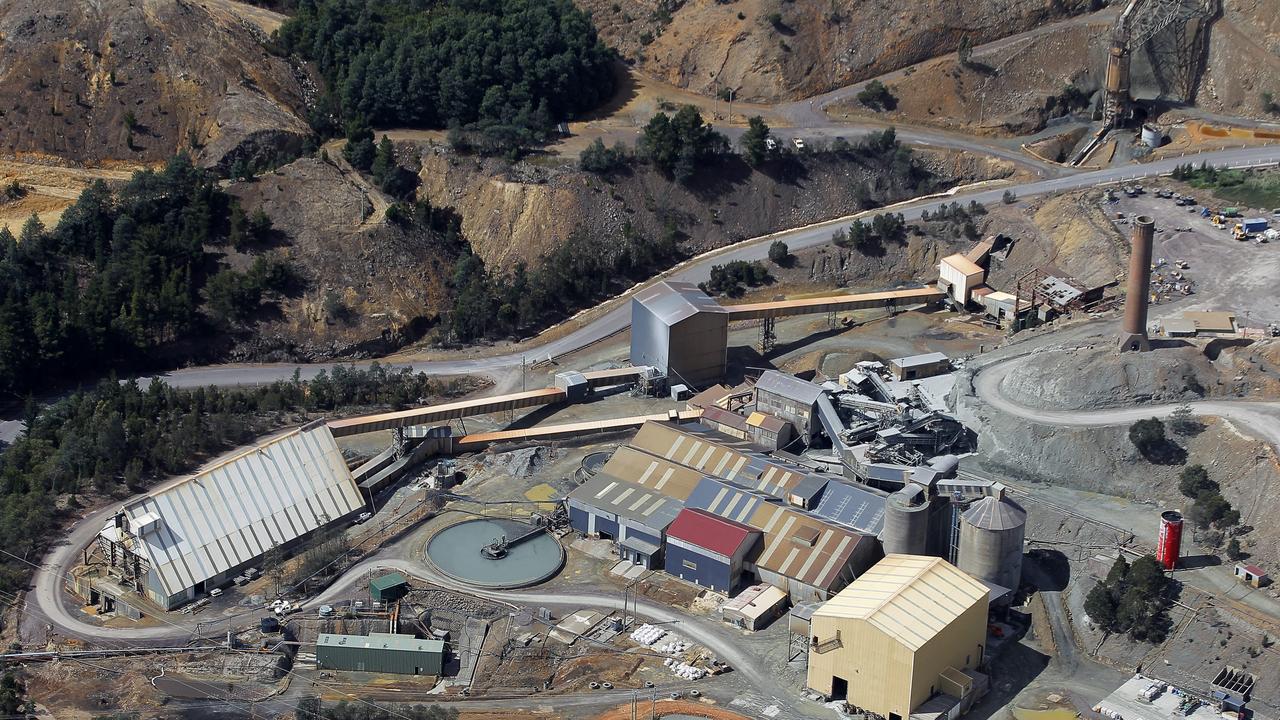

In Queenstown, the Mt Lyell copper mine closed in 2014 in the wake of worker deaths, with the result that about 200 employees were made redundant. There are moves afoot, however, to reopen the mine.

The “main issue,” however, is housing, Mayor Pitt said, a key cause of the DIDO/FIFO epidemic and an inhibitor of the population growth needed to replenish the region’s desiccated towns.

The council is investigating whether it may be able to release some of its land for development, while it also has its eyes on Crown land owned by the state government.

Other persistent issues nominated by Mayor Pitt included limited transport options – there is a daily bus to Burnie and that’s about it – and poor health outcomes driven in part by the unavailability of local allied health services.

It can be a lonely place, too, for newcomers, especially white-collar professionals with little connection to the region.

Primary schoolteacher Monica Cini taught at St Joseph’s Catholic School Queenstown between 2019–22.

She found a “limited variety of social environments, especially for those who have few connections,” and also struggled with the “limited fresh produce at shops, especially by the end of the week, and at an expensive price margin”.

Ms Cini also found it “isolating” being so far from allied health services such as dentists, therapists and masseuses.

She did, however, look upon with wonder the “almost unmatched” environment, which she called “quiet, refreshing, [and] surrounded by greenery and wildlife”.

Ms Cini also looked favourably upon the “developing art scene”.

THE OPPORTUNITIES

Mayor Pitt said that a good place to start would be securing for the region a greater share of the wealth created by its mineral and renewable energy assets.

He said the council only received about $2m per annum from mining royals, as balanced against tens of millions collected by the state government.

“The state receives millions in dividends from renewable energy and fees from aquaculture, while the council and local community receive little,” he said.

Making more land available for residential development, whether it be Crown or council-owned, is another key action.

The UTAS paper into the effect of DIDO/FIFO workers also made a host of recommendations to draw more employees into permanent residency.

It advocated for incentives such as housing packages and tax benefits to be offered to locally based employees; improving the capacity of local businesses to service the resources sector; and further advancing the region’s local services, infrastructure and liveability.

But the West Coast can’t implement the UTAS recommendations alone: in FY21–22, council’s budget was just $11,654,859. It caters for an area that is only about 800 sqkm smaller than the county of Lebanon.

The changing face of the West Coast

In many ways, Queenstown couple Anthony Coulson and Joy Chappell, owners of the town’s Paragon Theatre, embody the changing face of the former mining outpost’s transformation into an arts and tourism hub par excellence.

Mr Coulson, Queenstown born-and-bred, was your “typical mining town person,” leaving school to take up an apprenticeship at Mt Lyell copper mine, “which everyone did at the time”.

Ms Chappell, meanwhile, was a newer arrival, relocating to Queenstown from her native Ulladulla, on the NSW South Coast, in about 2000, chasing adventure.

She took on Mt Lyell Anchorage and developed it into one of the town’s top boutique accommodation, which is how she came across Mr Coulson who, in 2010, had left the mining industry to capitalise on the region’s increasing tourism bona fides, founding an underground mine, wilderness and relics tour business.

Seven years’ later, the pair entered business together, purchasing Queenstown’s iconic theatre, built in 1933 during the town’s mining heyday, from Dr Alex Stevenson, who had begun the process of lovingly restoring the grand old dame in 2003.

Mr Coulson said that Queenstown’s transformation could be traced back to the Franklin River Blockade in the early 1980s.

“That changed everything really – environment and conservation, wilderness became the big ticket. A lot of my generation embraced that,” he said.

“I love the new Queenstown where the focus is really on being on the frontier of the edge of the world, where you can see the wilderness.

“I do also deeply engage with the historical and cultural aspects, the hard, gritty mining pioneer stage of the place, the massive wealth that was generated here.”

The return of wealth would be handy. Like the rest of the region, what’s desperately needed at the Paragon is a fresh injection of capital – while the inside of the theatre has been returned to its glory days, money has run out to restore the exterior, especially the art deco facade.

One thing Queenstown and the rest of the West Coast has in abundance, however, is time.

“We are the current custodians, but its real ownership is Queenstown. The theatre is part of the heritage of the whole place,” Mr Coulson said.