Narcos on the front line: Cartel jungle labs for cocaine and meth exposed

Bang, bang, bang. A heavy weapon fires four warning shots before rapid machine gun fire. This is what’s inside Mexican cartel drug labs. Watch episode 3 of our Narcos on the front line series now.

Narcos on the Front Line

Don't miss out on the headlines from Narcos on the Front Line. Followed categories will be added to My News.

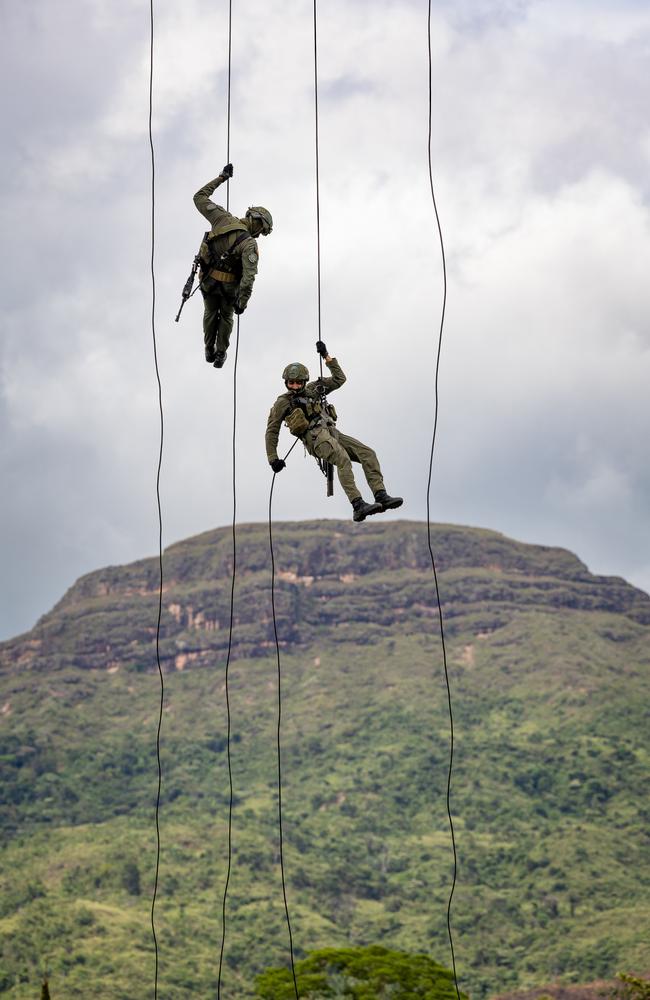

Exclusive: Hidden in the jungle, Colombian commandos wait.

Wearing camouflage gear, body armour, and carrying extra magazines of ammunition on their chests for their M16 machine guns, they surround a cocaine lab.

The planning takes months; the labs can take days to reach on foot.

The Commandos train for years for this moment knowing they are up against heavily armed cartel members who view a slain police officer as a trophy.

They take no chances.

Boom! An explosion signals the start of the raid.

Bang, bang, bang, bang. A heavy weapon fires four warning shots. Then follows rapid machine gun fire.

Watch episode 3 of our Narcos on the front line docuseries above.

The cocaine criminals have no idea from which direction the shooting is coming; they still cannot see the camouflaged commandos.

The commandos materialise at what feels like the same speed as their machine gun fire.

In 13 seconds, the raid is over.

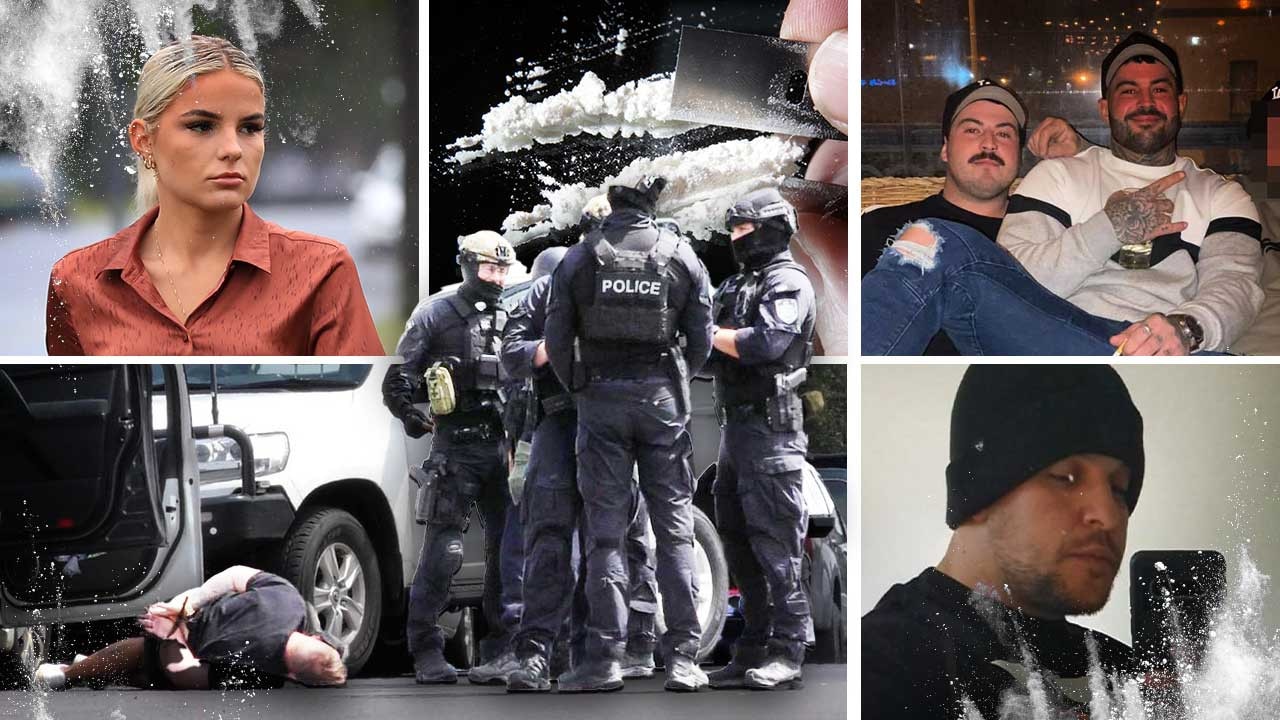

The cartel members are lying on the ground, hands behind heads, fixed in the sights of the M16s pointed directly at them. Drug cooks are arrested; cocaine is seized.

“Fire in the hole”, the commandos shout in Spanish, as they blow apart the jungle lab that can produce hundreds of millions of dollars worth of cocaine.

Black Hawk helicopters are on standby to fly out the commandos and their prisoners.

The helicopters cannot be used at the start of the raid because the sound of their blades would have given away the element of surprise.

These labs are lucrative, and heavily guarded.

The whole operation takes less than 30 minutes. The cartels have not time to regroup and call in reinforcements.

That’s how an exercise at Colombia’s world-class training centre in the Colombian jungle played out when we visited.

The 171ha facility is called Cenop, which translates into English as the International Police School for Peace.

Raids like the one we witnessed happen every day in Colombia’s Andes mountains, the only place in the world where coca plants – which provide the base ingredient for cocaine – grow.

More than 70 per cent of the world’s cocaine comes from Colombia; the rest is grown along the same mountain range in neighbouring Peru and Ecuador.

“The production of cocaine is dirty, disgusting. There’s no way around that,” an Australian Federal Police officer based in Latin America said.

“And you can put it in a nice light, but you are still using petrol, cement and sulfuric acid to produce the cocaine,” he told the Narcos on the front line special investigation.

AFP Assistant Commissioner Kirsty Schofield was shown the work done at Cenop by her Colombian National Police counterpart Eddy Duran.

Cenop also has a sniper firing range and an explosive testing ground.

Different types of coca plants are also grown here and used to help Colombian police identify the plants when they are oneradication missions in the jungle.

All coca plants need to be pulled out from the root by hand, mainly by police but sometimes with help from contracted civilian labour.

Those workers need to be flown in from other areas; the locals are too scared because they fear the cartels will kill them when the police leave.

Aerial spraying, which used a foam that had the same chemical ingredient as weed killer Roundup, was banned in Colombia in 2015.

Agent Luis Alberto Cepeda Arias – a respected chemist in the Colombian National Police – detailed the process of how cocaine was made and the cocktail of deadly chemicals used by the cartels.

As many as 500kg of coca leaves are needed to produce 1kg of cocaine, with workers paid just $A22 for 125kg of leaves, whichare ripped off the trees by hand.

That’s more than they could earn cultivating other crops, however, the cartels force many of them to plant coca.

Those leaves are cut into fine clippings with a whipper snipper before cement is added.

That mixture is added to a 44-gallon drum of petrol, which also can contain sulfuric acid, ether and ammonia.

A chemical reaction in the drum separates the leaves and cocaine hydrochloride – the active ingredient in cocaine.

“There is no way I’m putting any of that in my body” Assistant Commissioner Schofield said after viewing the process.

“And I would recommend no one ever puts anything like this into their body,” she said.

“You can smell the gasoline on it, you can smell it throughout all of the different stages. The gasoline smell is extremely strong.”

Farmers then take a brown sludge from the petrol mixture known as cocaine paste and dissolve it in hydrochloric acid before adding ammonia.

That’s then sold to drug cartels for as little as $1500 a kilogram.

The cartels dry the paste, turning it into powdered cocaine, which is shipped to countries such as Australia, where it sells for $300,000 a kilogram.

The cocaine trade also comes at an environmental cost for Colombia’s 50 million people.

“All the chemicals end up in their waterways,” Assistant Commissioner Schofield said.

“So it’s a huge environmental hazard for this country.”

We also visited Mexico where the Secretaria De Marina – the nation’s navy – showed how it tackled the deadly ice labs.

The navy has a unique role in Mexico compared with Australia’s equivalent force.

The highly respected naval officers patrol the seas but also take the fight to the cartels in the jungle.

The navy is seen as a specialist force, living an almost monastic life of 16-hour days on base.

The Marines are the front line against the war on drugs in Mexico, which is a global shipping point for cocaine and a major producer of ice.

Just one makeshift meth lab can produce seven tonnes of ice, almost equivalent to the amount used in Australia each year.

“Normally these clandestine labs are located in a jungle or near to a small town,” a Marine, who spoke on condition of anonymity,said.

Mexican drug cartels import chemical precursors from China to produce ice, with the final product costing about $400 a kilogram.

That same ice can sell in Australia for up to $250,000 a kilogram.

“They do basically everything in the clandestine lab,” the Marine said.

“They prepare the drugs, they cook all the drugs there until the final product is ready.”

Originally published as Narcos on the front line: Cartel jungle labs for cocaine and meth exposed