Critical evidence lost: Police errors in Rachelle Childs’ murder case

Multiple failures occurred when Rachelle Childs’ burning body was found. See the damning list and listen to the latest episode of the podcast now.

Dear Rachelle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Dear Rachelle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Exclusive: One of Australia’s most enduring murder mysteries was so poorly investigated that critical evidence was irretrievably lost, it can be revealed.

Police tasked with finding Rachelle Childs’ killer did not “have an idea in the first 48 hours”, and stubbornly refused to hand over the case to a unit with more expertise.

The fundamental policing errors, which have haunted the high-profile police search to identify Rachelle’s killer, are exposed in the third episode of the Dear Rachelle cold case podcast, launched on Thursday.

WATCH THE VIDEO ABOVE: WHY THE KILLER CHANGED THEIR PLAN

Twenty-four years after her burning body was found far from home in Gerroa, south of Sydney, the True Crime Australia investigation has unearthed a stunning succession of missteps and a failure to follow “basic 101 investigation methodology”, including:

- CCTV footage from service stations which might have showed Rachelle and her killer travelling in her car was seized by police – and lost.

- Some phone records for Rachelle and the persons of interest in her killing were sought only after they were no longer available.

- Attempts to verify or disprove alibi statements of persons of interest remained incomplete many months after Rachelle’s death.

- DNA lifted from a bedsheet from Rachelle’s car was eventually found to be from a police officer charged with preserving the evidence.

- High level plans to hand over the complex investigation to the NSW homicide squad after 48 hours were kiboshed by a local senior constable, in a decision said to have cost evidence which was not and never can be recovered.

LISTEN TO EPISODES 1-15 OF THE PODCAST BELOW:

Then Detective Sergeant Mick Ashwood supervised a homicide squad review of the initial investigation.

He said NSW police failed Rachelle and her family.

“When you don’t have an idea in the first 48 hours, it makes it harder to solve,” Mr Ashwood said.

Veteran Victorian homicide detective Charlie Bezzina said there was always a methodology to follow – “run every rabbit down its burrow and never leave any stone unturned”.

He said that this thoroughness was not applied in the initial investigation into Rachelle’s death.

“Once crucial evidence is discarded or lost you can never go back,” Mr Bezzina said.

“Basic 101 investigation methodology in this case has either been ignored or not followed up.

“Families place their trust in investigators who in this case have significantly let them down.”

According to then Detective Leading Senior Constable John Bryant, in a statement written four years after Rachelle’s death, the investigation review revealed that “approximately 90 tasks in the Bargo and surrounding Southern Highlands area” were “largely incomplete or yet to be undertaken”.

“These tasks spanned across each major line of the investigation, from Victimology, Persons of Interest, Canvassing, the investigation of public information, and the investigation/elimination of persons who were closely associated with Rachelle Childs,” he said.

Coroner Jane Culver also found floors, recommending in 2008 that a NSW police homicide squad detective should be the leading investigator in any suspicious death in the first 48 hours. After 48 hours, according to the recommendations, the homicide squad should consult with local police command to determine which unit of the police force should continue the investigation.

Murder investigations are inevitably fogged in stress, pressure and emotion. Mistakes can and do happen.

Rachelle’s case was muddled by the distance between her last known whereabouts and the site of her remains, as well as four or more secondary crime scenes.

Two main roads link Bargo, to the south-west of Sydney, and Gerroa, 110km away.

It’s thought probable that the killer and Rachelle made this trip in her 1978 Holden Commodore.

If so, they almost certainly would have stopped for petrol, given Rachelle, 23 and always in debt, never had much fuel in the tank.

Unclear CCTV footage was obtained from two petrol stations near Nowra, NSW (which was never shown to the family in the hope that they could identify Rachelle).

Footage from other service stations was also obtained, but then misplaced by police some time before 2003.

A year after Rachelle’s death, five or six men were listed as persons of interest, in a grouping which would grow to nine men.

Mr Ashwood said the initial investigation had not “completed the lines of inquiry”.

“Your goal when you have a person of interest is to eliminate them from the investigation,” he said. “If you don’t eliminate them, then you’re left with a suspect.”

Only a sample of Rachelle’s phone records for the six months before she was killed – and those records of a key person of interest – were collected.

“Unfortunately, police can no longer obtain Vodafone records for either Rachelle’s or (person of interest’s) mobile phones,” Mr Bryant wrote.

Mr Ashwood found there had been “very little” victimology – insights into a victim’s habits, fears, perspectives and so on – completed after Rachelle’s death.

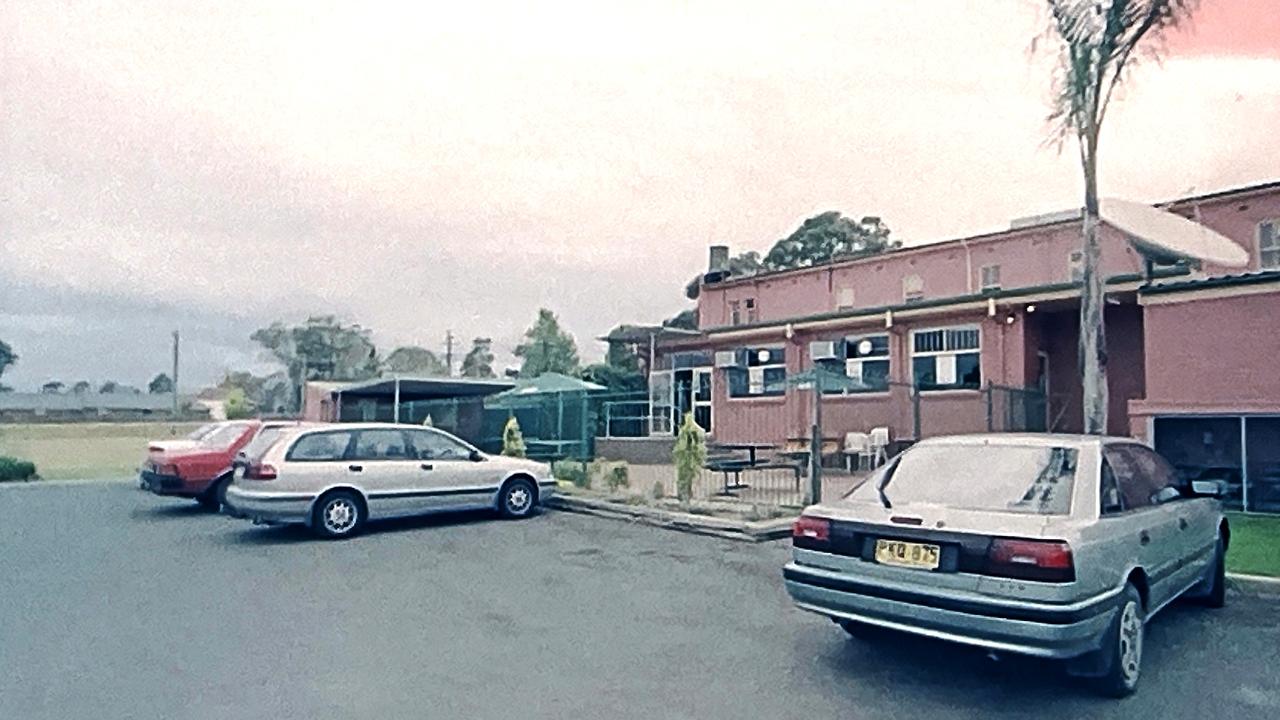

Rachelle may have gone into the Bargo Hotel, which had no surveillance cameras, on the night of her death.

Yet Mr Ashwood found that only a third to a half of patrons at the Bargo Hotel there at the time had been spoken to by police.

Unfounded rumours took hold and distracted investigators.

For example, it was suggested that Rachelle had planned to go to a party of the local chapter of a motorcycle gang – there was no party that night.

It was claimed that she was killed over drugs, but that too seems highly unlikely in the absence of any evidence.

After a year, investigators had confirmed no facts about the dramatic events between the last known sighting of Rachelle and the discovery of her body nine hours later.

After such time, Mr Ashwood said, the information gaps created a high risk that the case would remain “unsolved”.

For more information about our investigation, visit dearachelle.com.au

If you have any tips or confidential information, please contact investigative journalist Ashlea Hansen at dearrachelle@news.com.au.

You can also join our Dear Rachelle podcast Facebook group.

More Coverage

Originally published as Critical evidence lost: Police errors in Rachelle Childs’ murder case