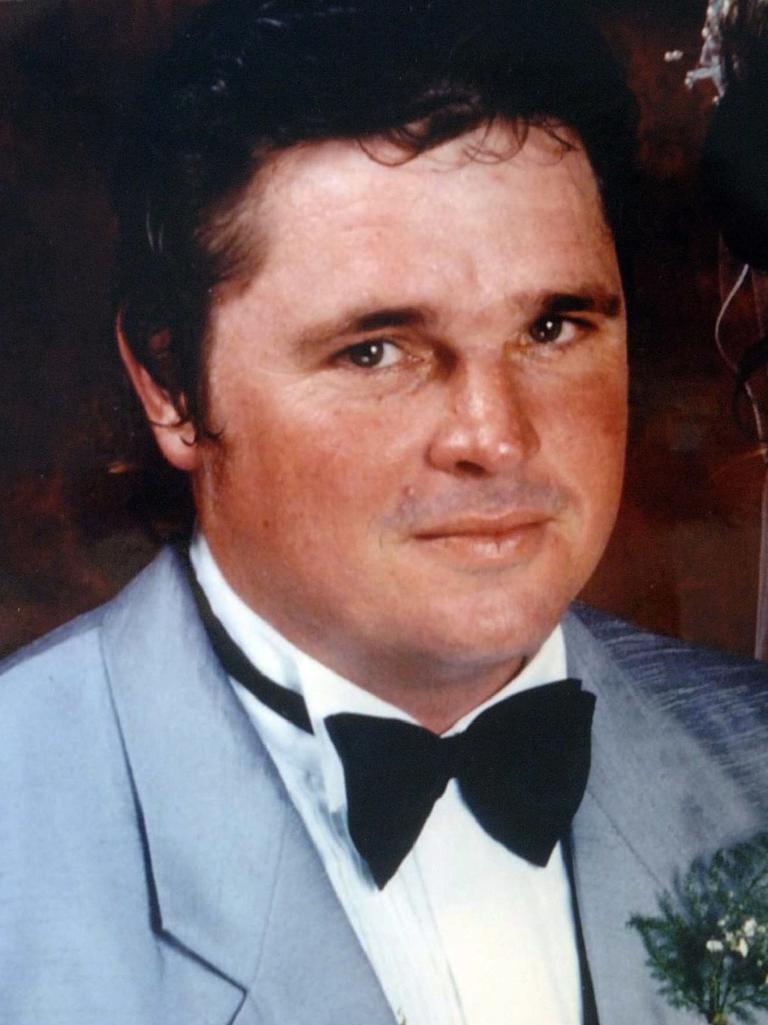

Bevin and Brad Simmonds cold case still haunting 20 years on

It is one of the most intriguing ‘missing persons’ cases in Queensland’s history and 20 years since a Cape York father and son disappeared, questions remain about their fate.

Cold Cases

Don't miss out on the headlines from Cold Cases. Followed categories will be added to My News.

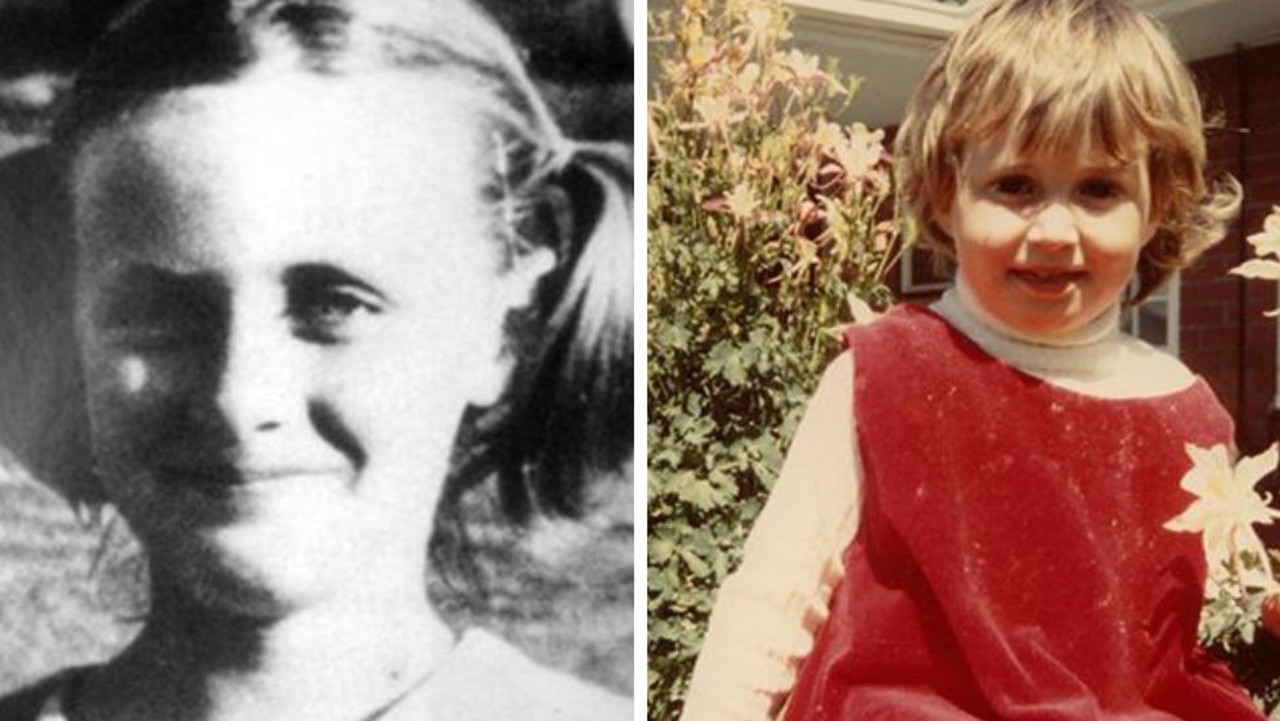

It has to be one of the most intriguing “missing persons” cases in Queensland’s history and, 20 years since Bevin Simmonds and his 10-year-old son Brad vanished from the face of the Earth, there are still police and amateur sleuths pondering their fate.

It was 20 years ago last Monday that the pair left their boat The Eldorado in a 5m-long dinghy to check shark nets near the mouth of the Coleman River in one of those shallow, chocolate-coloured inlets that dot the Gulf of Carpentaria.

They were never seen again.

Their disappearance is marked by a humble brass plaque on a waist-high Besser-block memorial in the small fishing town of Karumba, commemorating scores of people who have lost their lives at sea around Cape York.

Yet the fact that a 36-year-old father and his son vanished under clear skies and on calm seas while performing a routine task they had completed countless times before has never been treated as a maritime tragedy by a small northern-based community, which for generations has pursued an off-the-grid existence, way below the radar of mainstream Queensland life.

Fishing families dot the isolated waters of the Gulf of Carpentaria and have created their own subculture, which might be best described as “aquatic hillbilly” were it not for their wealth.

A few are multimillionaires, drawing massive incomes out of the sea and accumulating the sort of capital that allows for luxury 20m trawlers and expensive four-wheel-drives.

They live on trawlers and peg out campsites on the mangrove-shrouded shorelines, often clashing over fishing grounds.

Thin wires have been known to be stretched across small estuaries to knock some unknowing amateur angler out of their boat if they happen to wander haplessly into hostile territory.

Bevin was not known to be violent, but he was enmeshed in that life.

So was his son Brad who, despite a few minor medical problems, was a keen apprentice in the maritime world, seemingly determined to follow his father to sea where he would hunt the barramundi, salmon and shark that thrive in the nutrient rich waters of the north.

The cause of their disappearance and likely death remains a mystery.

One murder theory has been rejected by a court.

Two years after the disappearance of Bevin and Brad, Cairns Supreme Court heard a graphic and often disturbing tale of what police alleged actually occurred that June morning: cold-blooded murder.

There was no weapon, no body, not even a boat.

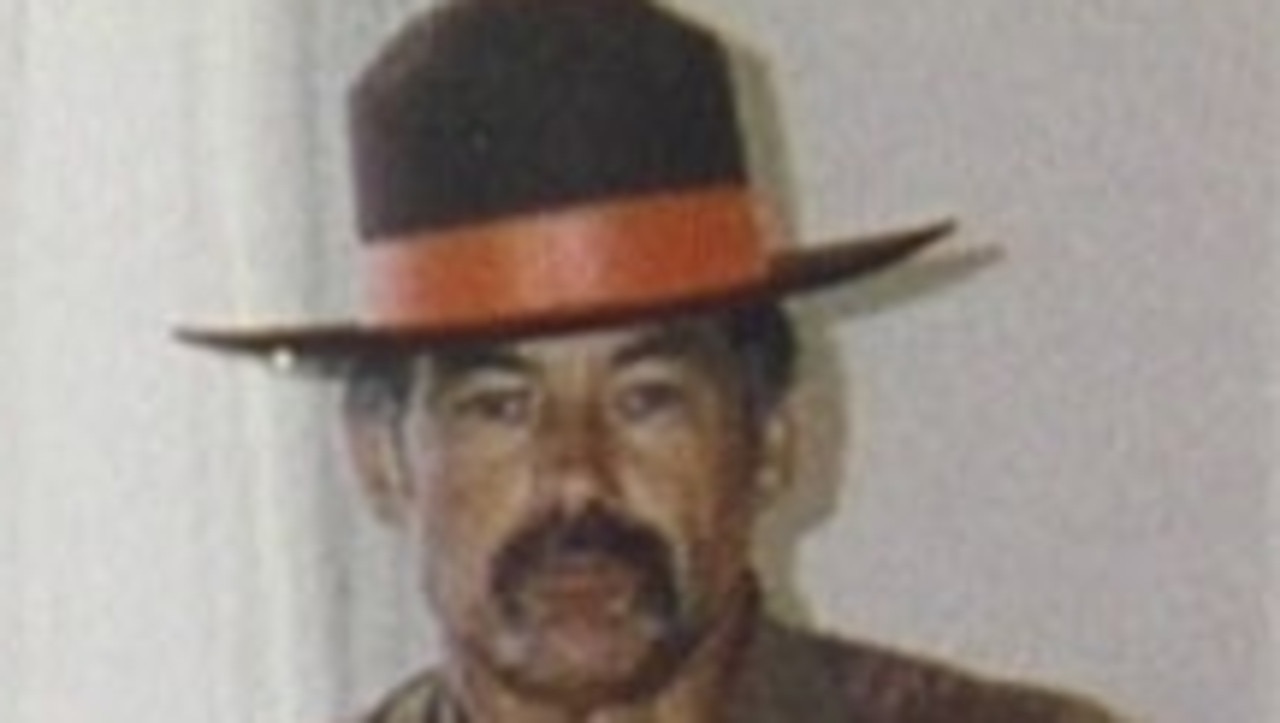

The court heard that Bevin had an enemy; Gulf fisherman Michael Gater was alleged to have been having an affair with Bevin’s wife Catherine, and who was known to refer to Bevin as “the little fat bastard”.

It was also claimed in court that Simmonds and Catherine, who lived together on The Eldorado, were in a constant state of warfare, screaming at each other in violent confrontations then retreating to their respective ends of the vessel while an uneasy truce prevailed.

Police, led by the dogged Ed Kinbacher, who has been involved in investigating almost every serious crime in the far north since becoming boss of the Cairns criminal investigation branch in 2005, believed they had enough evidence to file a murder charge against Michael Gater and his mother Joan.

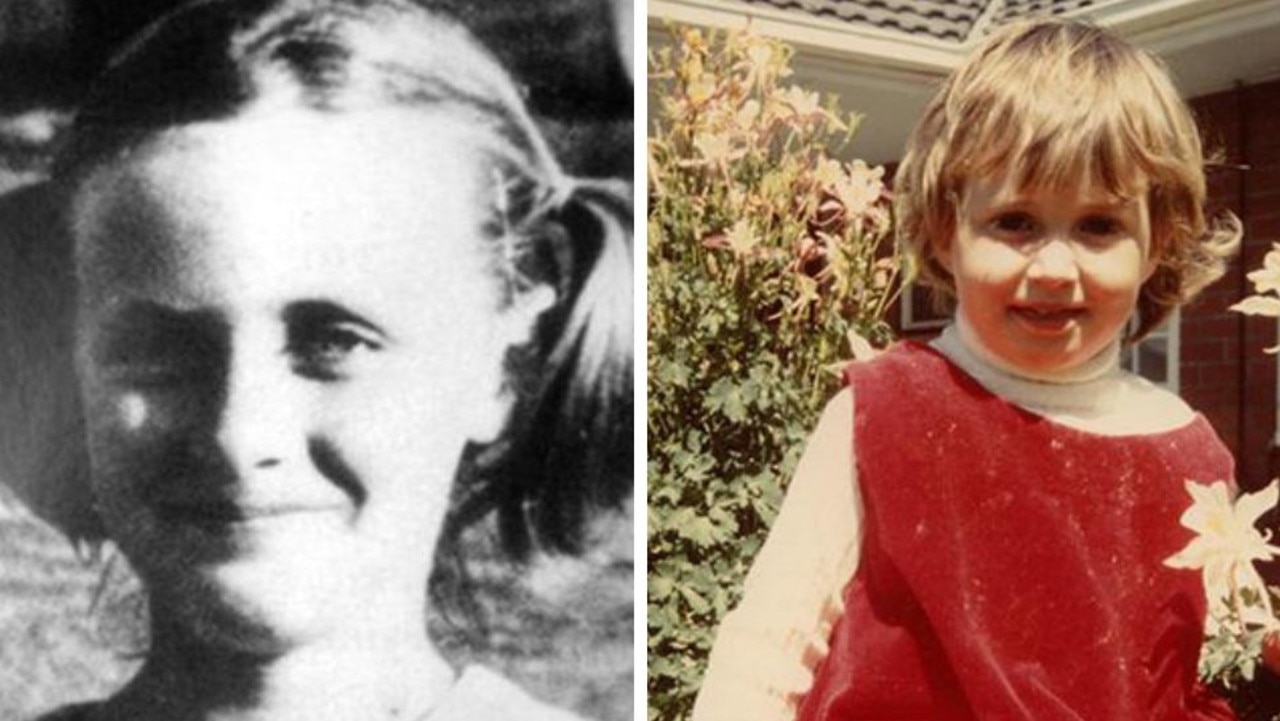

Joan, now well into her 70s, has long been recognised as the matriarch of the Gater clan and a key factor in building the Gater family’s wealth.

The court heard that Joan liked Catherine.

She liked the way Catherine both earned and held on to money and even offered her a $130,000 fishing licence, while her son Michael had once given Catherine a $3000 watch as a gift to win her hand in marriage.

Police alleged in court that on the morning of June 5, 2003, Joan and Michael hopped into their dinghy and ambushed Simmonds at the shark nets.

The Crown alleged Michael Gater shot Simmonds in the head.

The boy, it was alleged, also had to be killed because he was a witness.

The jury ultimately rejected both theories.

On October 10, 2005, the mother and son stood in the Cairns Supreme Court charged with murdering a father and son – the first time that has happened in Australian legal history.

With more than 40 hours of police surveillance tape and nearly 60 often highly colourful witnesses, the murder trial captured national attention.

Defence lawyer Greg McGuire, appearing for Joan Gater, described the allegations as both illogical and “laughable”, were they not so serious.

John Korn, for Michael Gater, described the case as absurd and raised the question why a man would kill the boy of a woman he loved, and whom the defendant knew personally and had even bought presents for.

The jury agreed with the defence and came back with a not-guilty verdict after nearly one month of hearing evidence.

Joan, speaking outside the court, declared that justice had been done.

Three years after the verdict, one of Bevin’s closest friends, Karumba fisherman Brian “Brains” Dunnett – who had threatened Michael Gater over what he believed was the murder of his friend – was found dead from a gunshot in a Weipa public toilet block.

Police determined it to be suicide.

The bad blood caused by the disappearance has continued running for much of the past two decades in the Gulf, and police say the case is still very much open and would eagerly accept any information from the public.

In Kinbacher’s view, the case was not simply a maritime tragedy but an incident that required the presence of a third party.

Now retired, he remembers how hard police worked collecting evidence all those years ago, and how gratified he was that there were some members of the community who were eager to assist police in determining what really happened to the father and son.

Part of the reason for the co-operation was that a child’s life had been lost.

“I suppose, when a child is involved, you find people who might normally put 100 per cent into a murder investigation are finding themselves putting in 120 per cent,” he says.

“There is something obnoxious about the loss of a child’s life, and it motivates everyone to find out what happened.”

THE FAMILIES LIVING OFF THE GRID

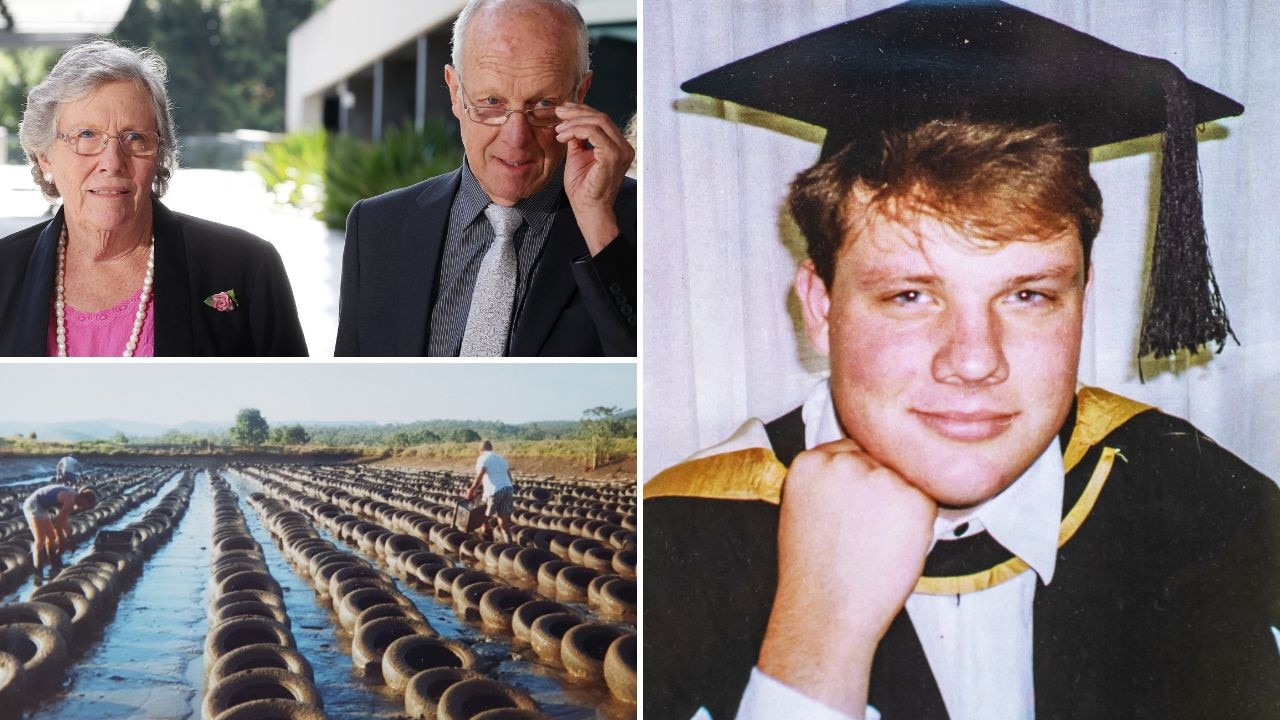

Those Queenslanders who increasingly seek an off-the-grid lifestyle probably have no notion of a largely forgotten tribe who live so far beneath the radar, most of us don’t know they exist.

Fishing families still dot the Gulf of Carpentaria, living in camps across the region but particularly on the wild western coast of the cape.

The lifestyle thrived through the 20th century and has tapered off in recent decades. But the presence remains.

Home is often a collection of ramshackle huts and demountable sheds, with trawlers joining abandoned catamarans and even an occasional decommissioned naval vessel dotting the muddy shore lines.

Fishing for barramundi is the main game and can bring massive financial rewards. But a credible source deeply familiar with the region says, when the shark fishing is good, it is possible to earn as much as $180,000 in as little as four weeks as manufacturers eagerly buy up a resource that can find its way into all sorts of fish-based products.

It was always, and still is, a rough and ready existence with territorial conflicts breaking out between rival fishing clans and the occasional bar room brawl.

There have also been a few recorded cases of people who are prepared to break the law.

“Finning’’ sharks and leaving the body to rot while selling the fin to Asian buyers, who still place a high value on shark fin soup, can reap a fortune.

Yet the future of the camp lifestyle is uncertain.

Tightening restrictions on the Australian Fishery, under legislation going back to the Fisheries Management Act 1991, continues to manage the fishery with an eye to more sustainable catch limits, limiting potential profits.

More Coverage

Originally published as Bevin and Brad Simmonds cold case still haunting 20 years on