Man falsely accused of cold case murder after father shares DNA sample

An innocent man’s life was ruined after his father donated his DNA to his local Mormon Church. Here’s why his story should make you rethink taking an ancestry test.

Science

Don't miss out on the headlines from Science. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Have you considered doing one of those DNA testing kits? Perhaps it was a Christmas gift from a relative or you were lured by the advertisements to find out whether you have Viking or royalty in your bloodline.

If so, you’re not alone. Thirty million people around the world have done one of these tests.

After a three-year investigation, for my new podcast, Secrets We Keep: Should I Spit, I discovered there are some serious questions which need to be considered before you spit into a tube and send it off.

Where was all this information going? Who owns it? What could be used for? And what are the privacy implications, not only for me but my relatives, past, present and future?

I discovered this data – this unique code which makes us who we are – is incredibly valuable to insurers, tech companies, pharmaceutical companies and the police.

This story took me to the heart of the Mormon Church in Utah, to the Australian Federal Police’s forensics lab in Canberra who are also vying for this data – your personal data.

What many people wouldn’t realise is that even if you decide not to do a DNA test yourself, chances are you are still are identifiable thanks to a distant relative who wasn’t so conscious of privacy.

The research that started this quest was done by former Columbia University professor, Yaniv Elrich who appears in the podcast.

“Since we’re all connected through deep genealogical ties, its enough to have a small database of one to two per cent of the population to identify everyone.”

DNA is unlike any other form of identification. Firstly, it is immutable, you are born with it, and you can’t change it. Secondly, unlike other biometric information like fingerprints, DNA is shared.

“I don’t need you in my database to identify you … DNA can never be anonymous,” Yaniv said.

What Yaniv had discovered was that when someone does a DNA test to find out their family history, it can reveal 300 people who haven’t done a test.

“You have this beacon that illuminates hundreds of people around him or her, and then you keep collecting these random beacons in the population, and suddenly you just have enough light that there are no more shadows. Everyone is being illuminated,” he said.

So how does it all work? The short answer is databases.

Combine DNA profiles in a database with the billions of records amassed by the global genealogy industry and you have a tool for identification which the world has never seen before.

The police call this powerful technique Advanced Familial Searching or FIGG (Forensic Investigative Genetic Genealogy). It originated in the US, hitting the headlines in 2018 when it was used to catch the infamous Golden State Killer via a third cousin.

But this wasn’t the first time police had taken DNA from a crime scene and tried to partially match it to DNA in a commercial database.

And when they do, it can go horribly wrong for innocent people like Michael Usry.

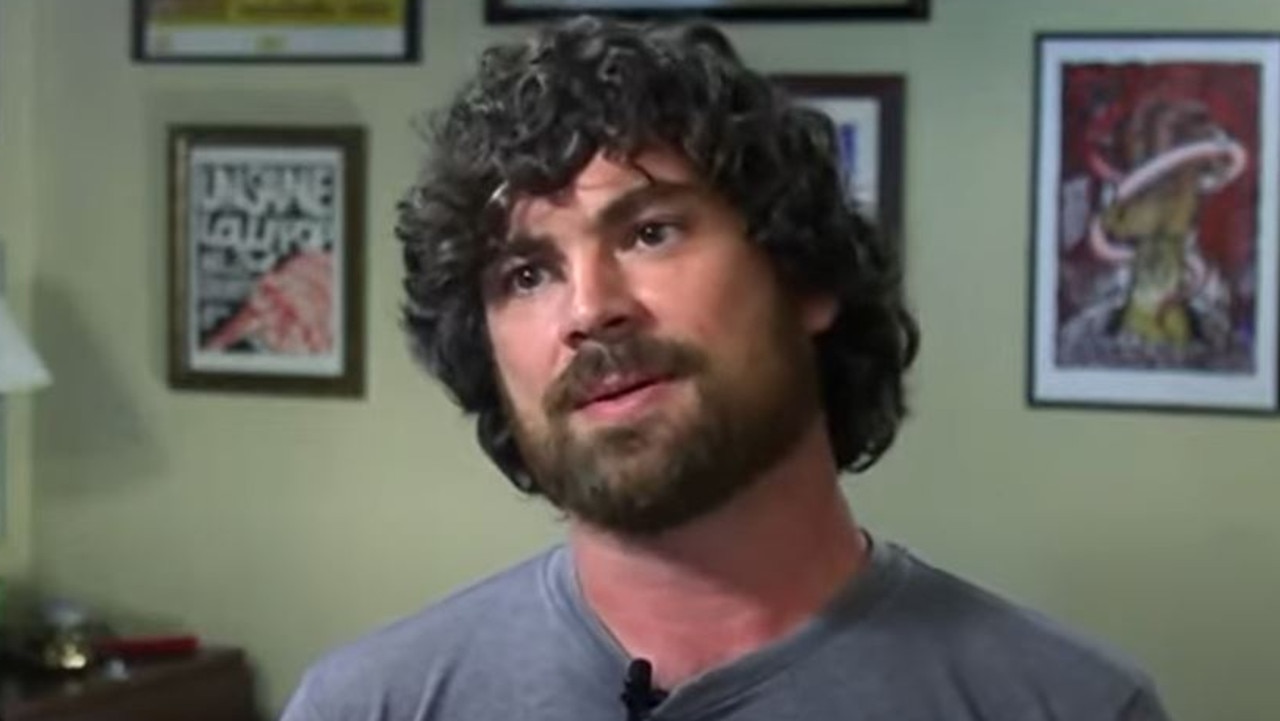

Michael is a filmmaker from New Orleans and was implicated in a cold case murder 3000 km away in Idaho solely through his DNA.

Michael had never done a DNA test, but Police found a partial match in a database owned by Ancestry.com which linked him to the crime scene. His father had donated his DNA years before to his local Mormon Church.

With police in Australia being trained by the FBI and starting to use FIGG, I needed to know more about Michael’s experience.

When we met in a hotel in Salt Lake City, Michael told me how police had built a circumstantial case against him based on a DNA lead which forced him to hand over his DNA sample.

“If they can start bringing people in just because they suspect that one person in the family might have committed a crime, then they (police) are going to greatly increase their criminal databases that they can search and bring in innocent people.”

Michael was eventually cleared, but for five years, the males in his family were under genetic surveillance and living under a cloud of suspicion.

“This is a major expansion of police authority that we have not seen before,” Michael said.

Unlike traditional DNA matching, where DNA from a crime scene is matched to DNA already in a police database, FIGG uses commercial databases to identify people who are not in the database.

Also, FIGG uses advanced DNA analysis techniques which look at the coding sections of our genome, the parts that hold information about our health, traits, biogeographic ancestry (ethnicity) and relatedness.

Authorities have developed internal guidelines around these new techniques however no new legislation has been introduced in Australia to govern its use, despite legal and privacy experts and even the Australian Law Reform Commission calling for more regulation for two decades.

Secrets We Keep: Should I Spit? is the story of how the consumer DNA industry has changed policing and is challenging our privacy.

All nine episodes are available now on the LiSTNR app.

Originally published as Man falsely accused of cold case murder after father shares DNA sample