Researchers warn Apple and Google users to ‘draw the line’ at sharing health data

DO you know what your Apple Watch shares about you? Researchers warn users to be wary, as private health data could be sold to the highest bidders.

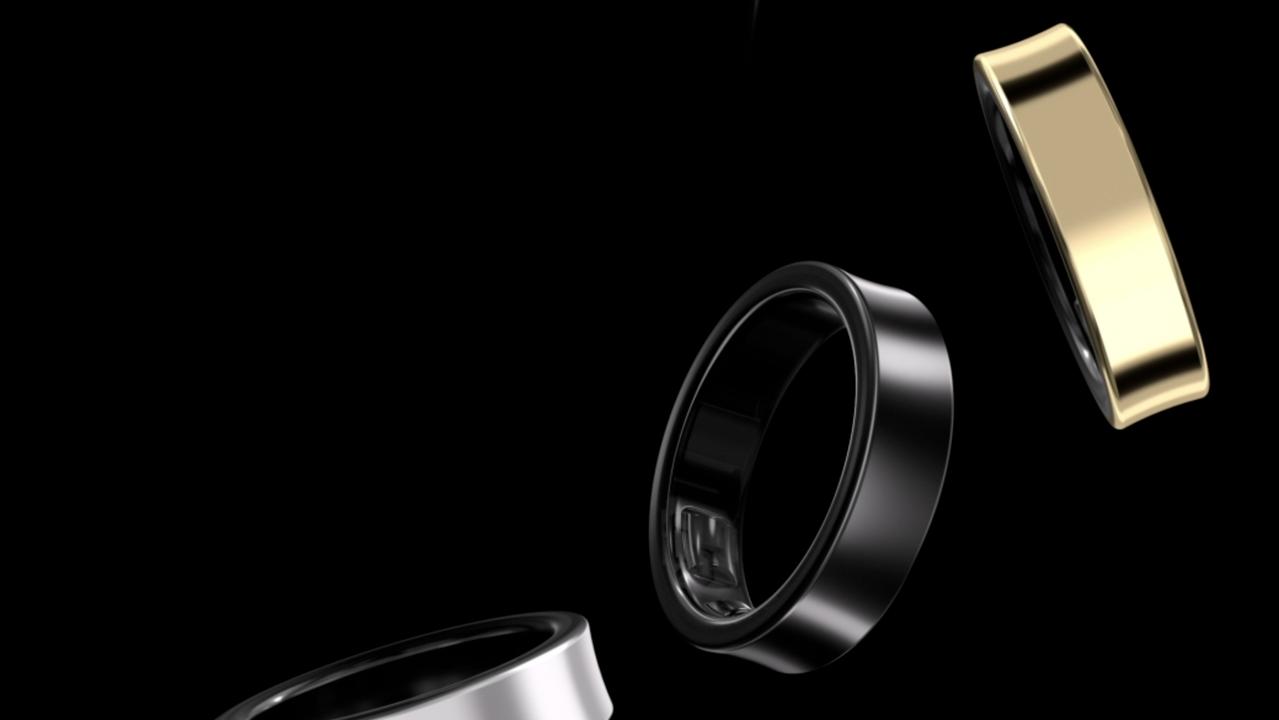

Wearables

Don't miss out on the headlines from Wearables. Followed categories will be added to My News.

AUSTRALIAN smartphone users are being warned to “draw the line” at sharing health information with technology giants Apple, Google and Microsoft to prevent the companies from secretly trading their “disease profiles” and “aggressively” marketing unnecessary services based on their step counts and heart rates.

Highly personal health information is currently collected by devices including the Apple iPhone and Watch, Google’s Android smartwatches, and Microsoft’s Band 2, and US researchers today warned their “closed-loop” systems could use and share the information in ways to “increase rather than reduce inequalities and injustices” in medical research.

The scathing assessment of Silicon Valley firms, published in the scientific journal Nature, called for tech companies to produce more open systems in which consumers could access all of their health records, and decide how information was shared.

Authors Eric Topol, from Scripps Research Institute, and John Wilbanks, from Sage Bionetworks, said health data platforms like Apple’s ResearchKit, and wearable technology was responsible for “tens of thousands of real-time observations collected from tens of thousands of people every day, even every minute”.

But the information was being held in “closed-loop systems” by private companies, according to the authors, rather than sharing elements with qualified medical research groups.

In some cases, like the diabetic wearable technology Enlite, even patients using the devices were not given full access to the medical information collected from them.

“We believe that closed-data and closed-algorithm business models in health — at scale — will hamper scientific progress by blocking the discovery of diverse ways to examine and interpret health data,” the report read.

“It is not hard to picture a future in which companies are able to trade people’s disease profiles, unbeknown to their patients.

“Or one in which health decisions are abstruse and difficult to challenge, and advances in understanding are used to aggressively market health-related services to people regardless of whether those services actually benefit their health.”

Mr Wilbanks and Mr Topol said the huge value of internet-connected health devices, estimated to reach $217 billion by 2020 according to eMarketer, did “not lend itself to ethically minded decision-making” from profitmaking tech firms.

Brisbane childcare centre manager Lyndel Alexander, who wears a TomTom fitness-tracking smartwatch, said she relied on the device to track her steps every day, and to provide important heart-rate and running pace information during exercise sessions.

But Ms Alexander said she “hadn’t really thought about” where the information was being shared and “I’m sure I’m not the only one who doesn’t read the terms and conditions”.

Neto Brasileiro, from Jetts Brisbane, also used wearable technology — an Apple Watch — to track exertion during his personal training sessions.

The report’s authors said the industry would benefit from “open projects” in which users could choose to share their information anonymously, but warned users to be wary of where their health information was currently being used.

“When it comes to control over our own data, health data must be where we draw the line,” they wrote.

Originally published as Researchers warn Apple and Google users to ‘draw the line’ at sharing health data