Melbourne Storm coach Craig Bellamy reveals the advice that steered him away from retirement

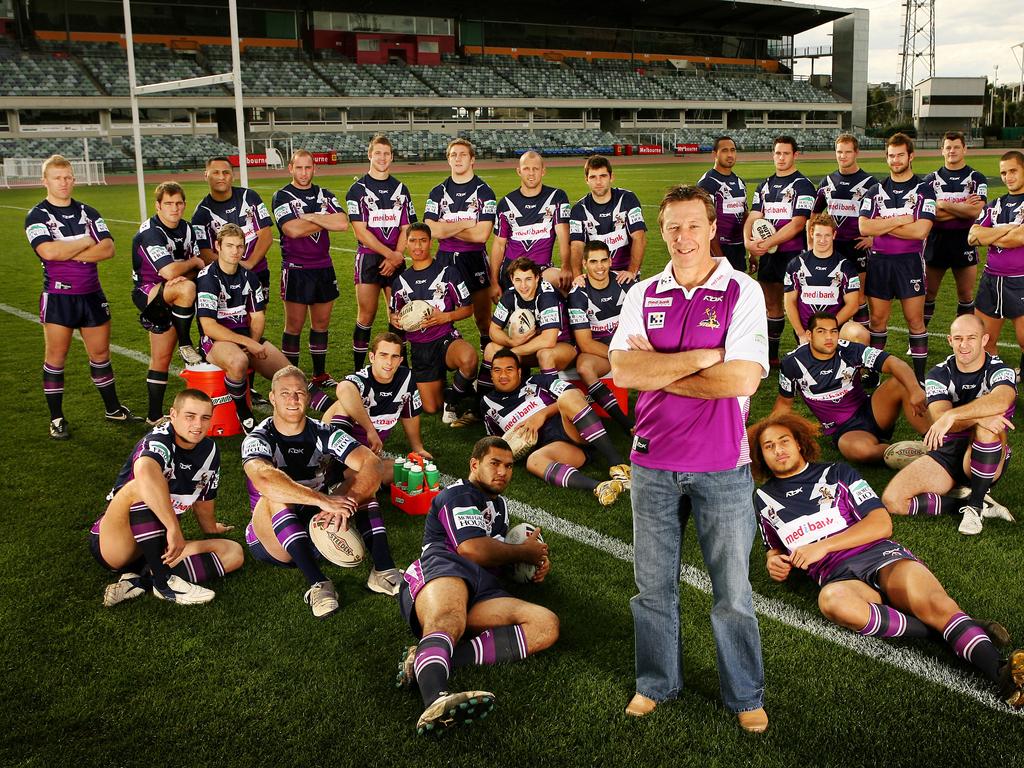

Craig Bellamy has cemented his status as one of Australia’s best ever coaches by becoming the second man to coach 400 NRL wins. So how does he do it? See the video.

Storm

Don't miss out on the headlines from Storm. Followed categories will be added to My News.

There is no formula.

That’s the first point about Craig Bellamy, the rugby league coach who long ago established his place as one of the best in the game.

There isn’t even a secret to his success. Those who seek magical insights into sporting excellence won’t find it by speaking to the Melbourne Storm coach.

He is a product of a faded era, of black-and-white TVs and little Australian towns that outsiders find little reason to visit.

Old school truisms, the kind of hand-drawn signs stuck to the walls of sporting change rooms, dot his thinking.

He’s about hard work, and honesty and humility, the kind of easy labels we all may aspire to. They’re hardly catchy, in a realm flooded with buzzwords. But he lives by them, far more naturally than he describes them. He abides by them.

Bellamy is an unlikely superstar, a bush kid who never shed the language of home. He’s averse to grandiosity. Don’t throw superlatives his way; he will shrink from them in his knockabout way.

“I don’t think I’m that good or better than anybody else,” he says. “But the one thing I am prepared to do is put the time and effort in. I was always brought up by my parents that if you want something badly enough, you will have to put in the time and effort.”

At 64, Bellamy is in a pretty good place.

Any thoughts of retirement are parked until the end of next year, in part because he still doesn’t know how he would fill his days if he did stand down.

More immediate concerns beckon.

After 22 seasons in charge at Storm, the longest consecutive stint of any NRL coach in history, his team has once again finished the season on top of the table.

He is resting players before the finals. He “isn’t trying to piss people off”, he argues, in response to commentators who have blasted the approach.

Bellamy is doing it his way. He always has.

This is the second point of his approach to leadership. There is no right or wrong way, according to Bellamy. There is only your way, fed by your values and beliefs.

Bellamy’s way includes sprays from the coach’s box, all spittle and emotion, in a throwback to the era in which he played and first coached.

During the latter moments of the 2020 grand final, he attacked an unsuspecting chair and later felt like a “bit of a dickhead”.

These outbursts loosely fit into his “honesty” and “care” ethos.

But Bellamy’s way also entails those off-camera moments, when he chats with players about the off-field, non-Storm elements of their lives. Or when he fawns over his grandchildren, whom he credits for extending his coaching career.

Since 2003, the Storm has played well enough to compete in every NRL finals series. Three flags could have been five for the record books, if not for salary cap breaches in the 2000s. The team won enough games to make the finals in 2010, when in punishment it played for no points, an effort of itself said to be a measure of Bellamy’s ethos.

Such consistency of excellence stands unparalleled in Australian sport.

As NRL giant Phil Gould once said: “Melbourne Storm is everything you want your club to be. They take kids, develop and nurture them, and turn them into champions. Every supporter would love to have a team like Melbourne Storm.”

Bellamy is the emblem and driver of this successful culture. He’s an older bloke who hasn’t changed a bit. Yet he is also someone who thrives as an observer of societal and generational trends.

He hates how young people seem stuck to their phones. He thinks some of them are more entitled of nature than they once were. He doesn’t understand social media and doesn’t want to. But he understands these young men so well that he brings out the best that they have.

Storm football manager Frank Ponissi says: “Even though the age difference between him and the players continues to increase, it hasn’t changed his relationship with them.”

Bellamy is a here-and-now kind of operator. He’s better with the disappointments these days, and he’s always figured that you can worry about tomorrow.

As Ponissi says: “One of his great strengths is his simplicity. Everyone thinks Craig is this mad professor who has this abundance of rugby league knowledge. Of course he’s got a terrific knowledge of rugby league, but his ability to turn the complex into the simple is pretty impressive. He just makes things so much clearer for the players that they know exactly what’s expected of them.”

Bellamy learned under two other great NRL coaches, Tim Sheens and Wayne Bennett, who is still coaching at 74. Those years were instructive, largely because the winning approaches of Sheens and Bennett had so little in common.

Bellamy bows to the AFL’s Alastair Clarkson (old school) and Craig McRae (new school). He admires Manchester United’s Alex Ferguson, known for “hair dryer treatment” verbal sprays, which ruffled the hair of his players. “There’s no use beating around the bush,” Bellamy says. “You’ve got to say what you’re thinking and go from there because if you’re not being honest it’s not going to improve, it’s not going to get better, it’s not going to help the team.”

Ponissi cites Bellamy’s famed ability to develop players who had struggled elsewhere. Bellamy himself speaks of Brett White, a player who couldn’t get a senior game at St George Illawarra, then starred in more than 127 games at Storm.

“There’s an identity that teams have,” Bellamy says. “Certain players will thrive in that identity and other guys won’t.”

At Storm, that winning DNA is wrapped up in hard work. “I think in my 22 years here, the one thing I haven’t lost is my work ethic,” he says. “If I expect everyone to put in that time and effort, then I’ve got to do that as well.”

Bellamy’s parents are gone now.

At 20, he lost his dad in a quarry accident. Mum, a very visible presence in NRL circles, died a couple of years ago.

Their influence remains immeasurable. Norm Bellamy preferred fishing and hunting to sport. “He was always really supportive,” Bellamy says. “He didn’t know much about footy and never tried to tell me what to do on the footy field. But Mum did.”

Norm used to say that you should treat people how you want to be treated yourself. Mum Betty was more fiery. She would say that you should treat people how they treat you.

Lessons in common courtesy resonated in a young Bellamy.

“We all get different values from our mums and dads and our school teachers and junior coaches and teammates and our school mates,” he says. “That’s probably the one that just stuck with me.”

He is still numbed by the loss of his mum. She backed him through every club change, as both a player and coach. There was a mother/son bond which he never tried to mask.

He hasn’t been back home to Portland, a couple of hours northwest of Sydney, since her passing. It feels too painful to visit.

“I miss her a fair bit, “ he says, with his customary understatement.

Other familial influences have been less expected. When granddaughter Billie arrived, colleagues and players noticed an instant change.

Billie the baby was quickly nicknamed “the Pacifier”. “I’ve seen him after games where we haven’t played well and lost and he’d be really fired up,” Ponissi says. “And suddenly the grandkids walk into the dressing room and it’s like we’ve just won the grand final.”

Bellamy hadn’t much considered the power of grandchildren before his own started appearing. He felt calmer, as others pointed out. He mellowed in his approach. Losses were not as enduring in the aftermath. He had regular visits to look forward to.

“I don’t know if that’s what happens to most people but I think it happened to me,” he says.

Team captain Harry Grant puts Bellamy alongside his mother and father as a life influence. He says that what the audience sees – Bellamy’s tendency for game time histrionics – can be slightly misleading.

“It’s a week-to-week understanding of how he gets the best out of you,” he says.

“A lot of people see the 80 minutes of Craig being very animated and very worked up in the box, but that’s far from his actual self. He puts so much time and effort into preparing the 17, 18, 19 players who are going out to play to the best of their ability.”

What sets him apart? Is it his care or his effort or the example he sets?

“I think all of the above,” Grant says.

“I think the effort comes because he cares so much not only about results in that week but more so he wants the individual player to get the best out of themselves and be the best player that they could possibly be. He wants the best for the team. He wants sustained success. I think there’s a responsibility with Melbourne Storm being such a good side for so many years that we continue that.”

The lighter Bellamy likes to sing Aussie hits from the likes of The Angels and Cold Chisel. He will often be sprung, at the front of the team bus, wearing headphones and singing along more loudly than he realises.

“No, he can’t sing, but he thinks he can,” seems to be the universal response to these shows of happiness.

Some of Grant’s favourite off-field moments come when he sits next to Bellamy on a plane or bus. “He’ll tell you some stories about his family or people he has caught up with recently,” Grant says. “He can get very personal with that sort of thing.”

Bellamy has thought about retirement before, notably in 2021 in the post-Covid pall, when he felt a fresh coach would be helpful to the Storm.

But he has since been steered by an old friend, who had retired and discovered that one of the challenges of retirement involves the need to get out of bed each day.

The mate said: “You’ve been working for so long for so many hours a week and all of a sudden you are doing nothing. I don’t think it’s going to be good for you.”

The quiet word had the desired effect.

“I think I would probably be retired by now if I hadn’t got that advice,” Bellamy says.

He can’t see himself coaching at 70. One more year, or 10, probably won’t redefine his longer record too much.

“If you do look into it deeply I think Craig Bellamy will go down as one of the best if not the best to ever coach in the NRL,” Grant says.

“You definitely don’t take that lightly.”

More Coverage

Originally published as Melbourne Storm coach Craig Bellamy reveals the advice that steered him away from retirement