Paul Green’s brain disease: family reveals cruel CTE diagnosis for former NRL star, coach

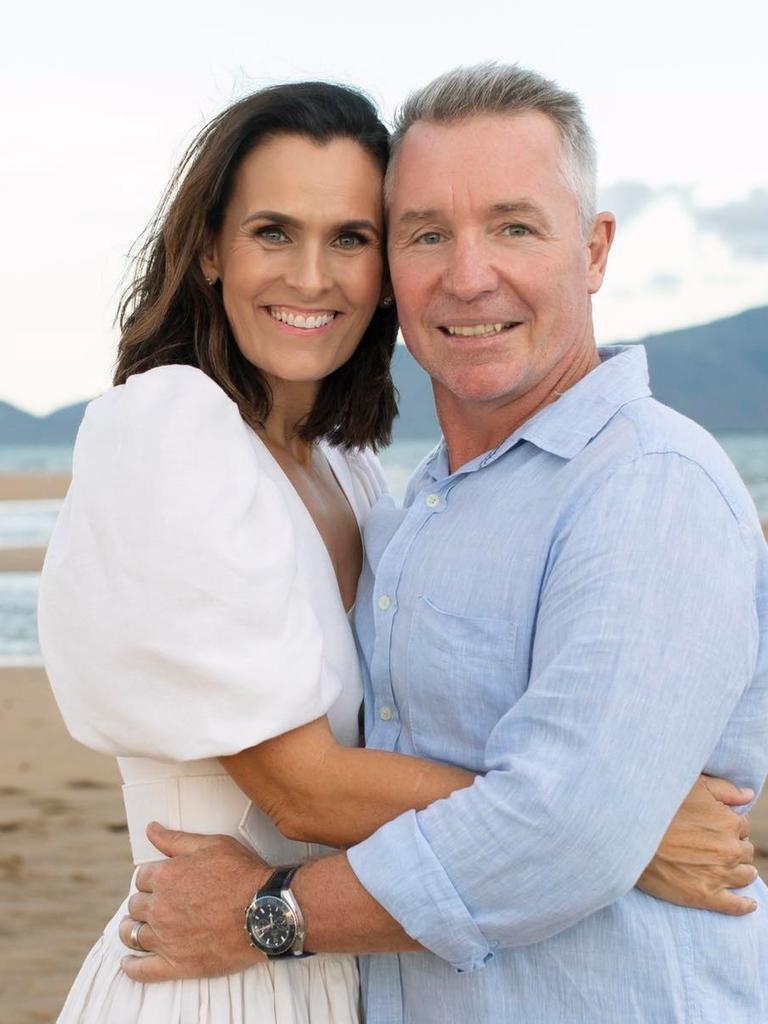

There were no signs. The rugby league great’s life was full. But in her first interview since her husband Paul took his life at the age of just 49, Amanda Green finally has some answers | WATCH

NRL

Don't miss out on the headlines from NRL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

There were no signs. Rugby league great Paul Green’s life was full; he had a loving family, a brilliant mind and driving ambition to coach in the NRL again. As his wife Amanda Green explains, their life together was packed with “big plans”.

“Paul wasn’t depressed, showed no signs of mental health issues, his family was everything to him,” Ms Green tells The Weekend Australian in her first interview since her husband took his life at their Brisbane home on August 11 at the age of 49.

Green’s death rocked rugby league. A giant of the game, he had left an indelible mark. First as a gutsy halfback notching up 162 games in a career spanning the Cronulla Sharks, North Queensland Cowboys, Sydney Roosters, Parramatta Eels and Brisbane Broncos that culminated in winning the Rothmans Medal.

But it was as the coach of the Cowboys that Green entered the history books, taking the team to their first grand final win, in 2015, in one of the great victories of the modern era.

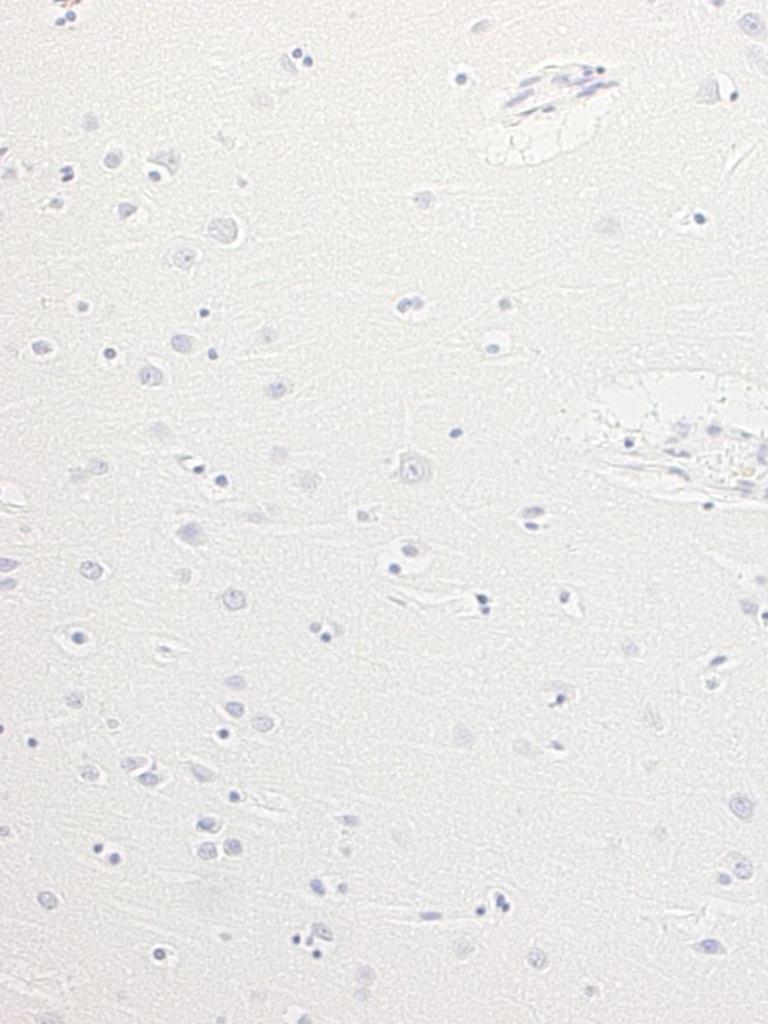

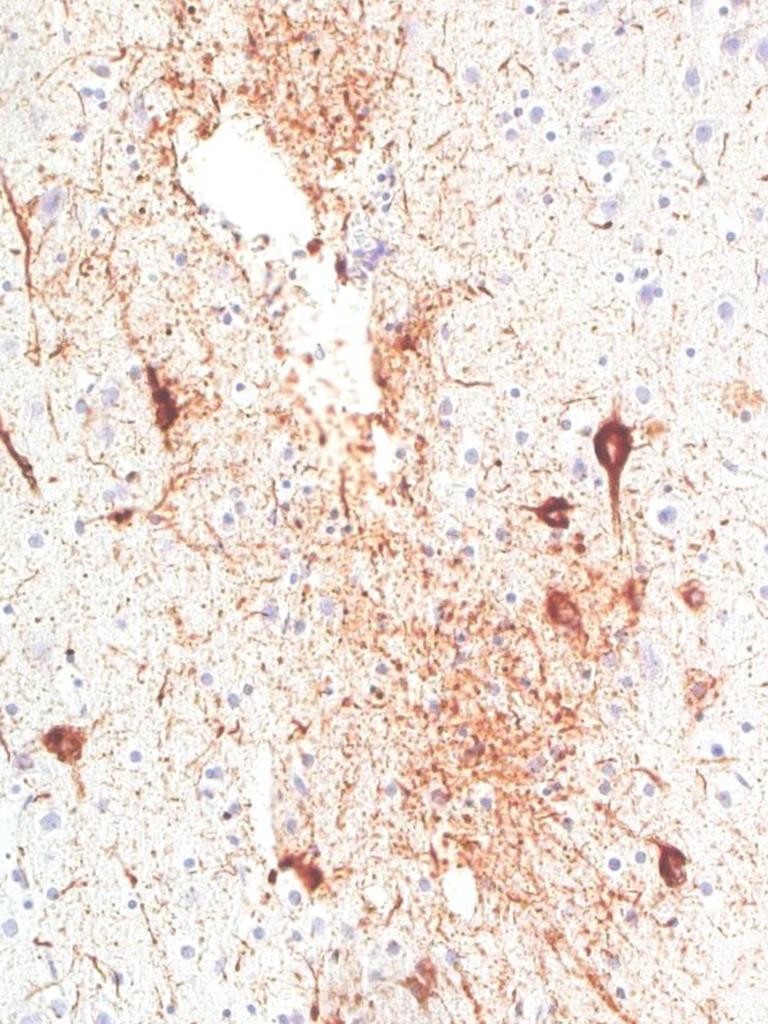

Now two months after his death, it can be revealed he had advanced CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy), a crippling brain disease linked to repeated head knocks – and it was one of the worst cases doctors had ever seen. Medical experts believe CTE can spark impulsive behaviour and may be a reason for his death.

The diagnosis has brought Green’s family some peace – at last they understand what he was going through.

Known as a deep thinker, he was a voracious reader who played the piano, a guy who could not only fly helicopters but who also triumphed in the rugby league world. On his final day on earth he celebrated their son Jed’s 10th birthday, laughing as he raced around a Gold Coast go-kart track with his kids and their friends.

That evening over birthday cake, pizza and a couple of glasses of red, the subject of an extended family decision was whether Green should go full-time into the “corporate” world or take an assistant coaching role at the Dolphins, alongside the masterful Wayne Bennett.

“What do you think about this opportunity?” Green, who loved to get people’s opinions, asked his brother-in-law, Jeff, as they sat at the dinner table of the family’s home in Wynnum, Brisbane. “Do you think I should take it?”

The following morning, Mrs Green was off to pilates. Before she left the house she went to the bedroom to see a still sleepy husband in bed. “I’m going to do a quick class, I’ll see you when I get home, get yourself going,” she said to him. When she returned, Green had passed away.

The devoted dad, loving husband, best mate to many, the “larrikin” with an “amazing mind” who was a Harvard Business School graduate, an NRL premiership coach who played the violin, was suddenly gone.

“I came home and found him … that was it,” Mrs Green says. “There were no signs. “We often talked about our future and what that looked like. I never once doubted that we would spend the rest of our lives together.”

Green’s death made no sense to those who loved him. There was no explanation for what had happened. In the midst of grief Mrs Green took a phone call from Michael Buckland, from the Australian Sports Brain Bank. He reached out and sensitively asked if the family would donate her husband’s brain for research. She said yes.

Last week Professor Buckland called her with the results. The neuropathologist had examined the former footballer’s brain and told her he had discovered one of the more “severe forms of pure CTE” he had seen.

Green, who played for five league clubs and made seven Origin appearances, played during a brutal era. No one can say exactly how may head knocks he suffered. He played in an era where playing on after a knock was a badge of honour. Green’s brain had been heavily impacted by CTE, a progressive brain condition associated with repeated blows to the head that can be confirmed only by a post-mortem.

Sense of peace

For Mrs Green and her children, Emerson, 13, and Jed, 10, the diagnosis has given them some “peace” and “relief”.

“I was able to sit Jed down and explain: ‘Daddy’s brain was sick, that’s why he did what he did’. The diagnosis has helped them understand what happened,” she says. “For my daughter Emerson it has also given her a sense of relief because of what’s being said out there [that Green had depression]. She now understands that he wasn’t in that space and there’s nothing we could have done, because he was sick. We just didn’t know it.

“This diagnosis has helped us understand and rationalise what has happened. It has given myself, the kids, some peace.”

The Greens are a “rugby league family”, who are grateful for everything the game has given them, but they hope Paul’s diagnosis will create a wider conversation and encourage more education about CTE.

“The incredible work of the Australian Sports Brain Bank and what professor Michael Buckland does is incredible, ground-breaking work, and without them we would have not had this information help us and the wider community get closure of Paul’s sudden passing,” Mrs Green says.

“My goal is to shine a light on Paul’s diagnosis, so we can advance our approach to detection, education, treatment and support for people suffering from CTE.

“I applaud the NRL for the improvements they are making to the game in regards to concussion and protecting players from grassroots to the professional level.”

Professor Buckland says “impulsivity” is one of its main symptoms of “stage three” CTE, which Green was suffering. “It was not him, it was the brain disease, he had an organic brain disease which robbed him of his decision-making and impulse control,” Professor Buckland says of Green’s sudden passing.

“The only known cause for the organic brain disease is exposure to repetitive head impacts.

“My feeling is he would have been symptomatic for some time and he was a smart guy, a remarkable man, with a lot of diverse interests, I suspect he would have been coping with stuff he didn’t understand for quite a while. He didn’t have mental health problems; he just couldn’t control stuff that was going on in his head.”

It’s only, looking back, that Mrs Green now can see some telltale signs of CTE and pinpointed the year of 2018, when Paul was still coaching the North Queensland Cowboys, as the turning point.

That year, with pressure ramping up on Green’s coaching, she saw unusual behaviour trends emerging in her once calm, focused and steady husband.

“I look back and I see he was doing these things that weren’t Paul,” she says. “By then he had at times difficulty controlling his emotions, impaired judgment, lowered tolerance, and displayed impulsive behaviour.”

Emotional struggles

At the same time as Green was unknowingly living with a degenerative brain disease he was immersed in a “brutal” NRL coaching environment.

CTE aside, it’s an environment his wife believes the NRL must improve in order to better care for the coaches and also their families.

“With or without CTE, coaches work in a very high-pressure environment that affects not only them but their families as well,” she says. “I would love to see more support for coaches and their families, as a legacy for Paul, who really cared for the wellbeing of those coaches in the game.”

And at work, the man who calmly, steadily, methodically, “excitedly” took the Cowboys to the grand final in 2015 – which they won – had started to change.

“Early on, he just took all the pressure in his stride, he remained focused. When he had a goal in mind he was determinedly on that path to achieve that goal,” Mrs Green says. “But then he started to change.”

After making the grand final in 2017, without superstars Johnathan Thurston and Matt Scott, and losing to the Storm, Green had high expectations for 2018. He told his wife he thought they could win that season. The Cowboys didn’t make the finals.

Again, Mrs Green was for the first time starting to see her husband wrestle with the weight of it all. “He wasn’t handling the pressure as well as he had in the past, but by now I think the CTE was starting to take hold,” she says. “Where in the past he handled the intensity of coaching with a certain calmness … I could see he was slowly starting to emotionally deteriorate.”

So many layers

Off the field, Green’s light started to dim a little.

The man that was always the life of the party, ensuring everyone was having a good time, singing, dancing (“he’d bring everyone along for the ride”), started to step back a little.

“As this took hold, it didn’t go all together, but he definitely wasn’t the fun, happy-go-lucky Paul we knew, and like I said, I put that down to the environment he was working in,” Mrs Green says.

At home the kids and Mrs Green were starting to, at times, “tiptoe” around him. The usually calm, adventurous, light-hearted dad was starting to have “surprising” verbal outbursts about innocuous things such as not sitting down for dinner together or not listening to him with intent.

“At home at times he was highly strung, we had to tiptoe around him, there was a lot of ‘Daddy’s working in a really highly stressful environment at the moment’,” she says. “It was just hard.”

The 2019 season came and the Cowboys didn’t make the finals again. Then Green was crushed when in February 2020 Maher lost his battle with MND. By the winter of 2020, life at the Cowboys for Green was going badly.

Green – who had been the architect of amazing success at the club, who took it to two grand finals and oversaw the 2015 victory in which Thurston clinched their first premiership with a field goal in golden point – was starting to lose favour.

Mrs Green remembers driving the kids to school and hearing on a local radio station “call in and tell us if you think Paul Green should be sacked”.

Still, the Greens had hope, he was an optimistic guy, the club would back him in. Green had worked hard on and off the field, establishing a strong playing roster, supporting the bid for a new stadium, he cared for the community. But as can be the nature of the game, it wasn’t enough.

On July 20, 2020, 10 games into the season, Green was called off the training paddock, into the Cowboys front office, and told he was no longer needed. His seven-season tenure, where he claimed two nines trophies, two grand final appearances, a premiership, a World Club Challenge, and coached three Dally M winners, was over.

The life they built in Townsville was over, they moved down to Brisbane and he worked hard to help Mrs Green at home.

He loved helping out, doing the school drop-offs. He was always a hands-on dad, and now he had the time.

Then Green was given another opportunity to coach for Queensland in 2021. And he didn’t just coach Queensland. Ever the innovator, a thinker, he called up contacts in the Queensland government to bring State Of Origin to Townsville. It was a masterstroke for which he was later lauded.

But a bad series loss saw his contract not renewed. “Everything that could go wrong in that series did go wrong,” Mrs Green says.

Green was disappointed after losing that Origin job but opportunities were coming his way. He found a purpose working with the leaders of the construction group BMD and was in the middle of developing a wellbeing app for the company.

“There’s so many layers to Paul, and whatever he put his mind to, he had so much belief,” Mrs Green says. “That’s one thing I loved about him. In his mind there was nothing that couldn’t be achieved. He believed if you put your mind to it and worked hard, you could achieve whatever you wanted in life.”

Sadness and loss

Work aside, he also had a “beautiful” and vast network of friends from all walks of life that would cushion him through the highs and lows of life.

He was constantly on the phone having a yarn to them. Every year he was off on a fishing trip or punters club trip. In a few months he was off to Italy to see his Harvard Business School mates.

Green’s phone, which still sits in the Green family kitchen, still pings constantly with WhatsApp group notifications from his Harvard Business School, fishing, punters club mates as they make plans.

But 2022 wasn’t without sadness and the loss of his dear friend, fellow fisherman and Australian cricketer Andrew “Roy” Symonds devastated him. Symonds passed away in a car accident. Green fell apart with grief at Symonds funeral. Amanda emotionally carried him through the streams of tears and sadness. Symonds had two kids, who are great friends with the Green family. Green was bereft that the Symonds kids had lost their dad so suddenly.

“I would never want you and the kids to go through this,” Green said to his wife.

Again, another moment in the caring dad’s life, which showed that he never wanted such harm or hurt to happen to his family.

At the dining room table, Mrs Green lists what they had in place, one that specifically included 10-year-old Jed and a boat. Green had decided to upgrade from a tinnie to a legitimate boat, a 50ft one, that was due to be delivered this week, so the pair could fish off the Brisbane coast.

This week he and Amanda were off to Orpheus Island to celebrate their respective 50ths with a group of friends.

There’s been an enormous outpouring of love for Green since his passing. There have been letters from old teachers and friends talking about how amazing he was. “Beautiful letters just letting me know how Paul impacted their lives and what an incredible person he was,” Mrs Green says.

Story to tell

People keep dropping by with food, and friends keep calling Amanda, just wanting to talk about Green.

“If there’s a chance that Paul’s story could help the next family spot the warning signs, and maybe be better prepared, then it’s a story that needs to be

Originally published as Paul Green’s brain disease: family reveals cruel CTE diagnosis for former NRL star, coach