1989 Canberra v Balmain NRL grand final: how a penalty changed the game

PART THREE: How a halftime speech and a Bill Harrigan penalty changed rugby league’s greatest ever grand final.

NRL

Don't miss out on the headlines from NRL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

SITTING on the Canberra bench wearing number 20 on his back was a Queenslander named Steve Jackson.

Truth be told, the 23-year-old was just grateful to be there. The week before he’d played in the Raiders’ losing reserve grade team and was convinced his season was over. He career was also at the crossroads. Signed up for $500 in 1986 from Mackay he was now off contract and in limbo. Injuries and inconsistent form meant he’d only started one first grade game in four years.

Adding to his woes Tim Sheens hadn’t used him as a replacement throughout the final series. So this time last week he didn’t have a club or a career. But then, after the first grade team had beaten Souths to qualify for the grand final, Sheens pulled him aside in the dressing room to offer him an opportunity.

PART 1: MENINGA AND PEARCE FACE OFF

PART 2: THE HITS THAT ROCKED AN NRL GRAND FINAL

“Jacko, bring your gear next week,” Sheens had said. “I want you as my last reserve. Being grand final day we can have as many players as we want on the bench so you’re on board.”

The offer had lifted Jackson’s spirits but, deep down, he knew there was little chance he’d take part in any on-field action.

“Even though (on grand final day) you’ve got all these fresh reserves, only a maximum of four can get a run so I didn’t think I’d be getting a start,” Jackson says. “But I didn’t care. I knew I’d be watching on the bench from the best seat in the house.

“And I remember when I was sitting there I kept looking at my arm badge with the Winfield Cup logo on it. Not only that, I had a brand new number 20 grand final jersey. I just said to myself ‘f*** it, I don’t care (if I don’t get on the field), this is unreal’.”

That week Jackson had got used to being left behind. On the Friday morning at the official grand final breakfast there weren’t enough chairs for him at the function so he had to stay back at the Camperdown Travel Lodge with the strappers.

Back on the field Canberra had finally troubled the scorers. A penalty goal put them two points closer to the Tigers and, with less than three minutes to go, it looked like the teams would return to the dressing rooms with the scores locked at 6-2.

As the clock ticked closer to halftime two exhausted sets of forwards packed into a scrum just five metres out from the Balmain line. The Tigers won possession and burrowed forward, seemingly content to play down the clock.

With each tackle Benny Elias got into dummy half or hovered round the ruck, every so often glancing up at the opposition defence. First tackle. Second tackle. Third tackle. Fourth tackle. Then it was the fifth and last tackle with just 90 seconds to go.

Once again Elias jumped into dummy half but this time he looked downfield and then to Canberra’s short side on his right. He’d noticed two things _ the fullback and the winger had dropped back expecting a kick. There was space.

“People talk about the danger time of a game being the 10 minutes before halftime,” Elias says. “We’ll it’s not, it’s the minute and the seconds before halftime.”

As the ball was played back to him Elias scooped it up and darted sideways. He quickly flicked it to Steve Roach who drew Dean Lance creating a hole for Andy Currier to run into. Suddenly the long-striding Englishman was in the clear and racing down the grandstand touchline.

With the cover defence coming across Currier kicked the ball downfield where Gary Belcher decided to gamble on the bounce of a football. He lost. The ball hopped away from him into the arms of Balmain winger James Grant who picked up Currier in support.

Belcher admits he got caught by surprise.

“It was the fifth tackle,” he says. “I was expecting a kick. But when that didn’t happen we scrambled to defend what was coming at us.

“All I remember is seeing Currier coming at me and I’m thinking ‘am I going to tackle him? Is he going to get through?’. But next thing he kicks it and I didn’t get it on the full. Balmain got a great bounce.”

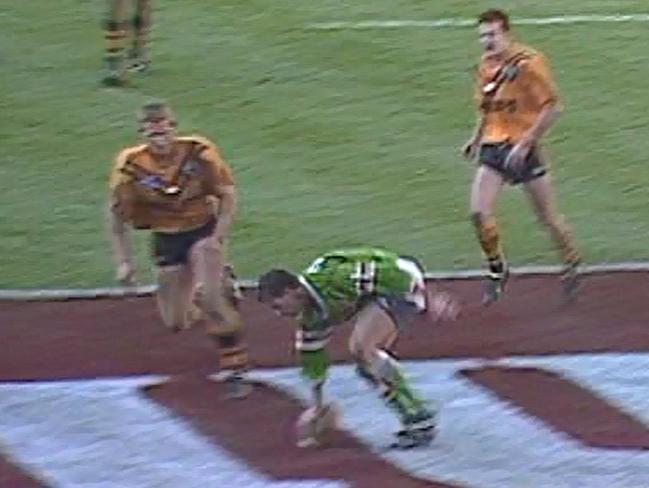

As Currier drifted left away from Belcher the giant figure of Paul Sironen loomed up beside him and he offloaded the ball to the 115 kilogram second-rower on the fly. For 16 thundering strides Sironen galloped towards the goalposts. Chasing him in desperation was Bradley Clyde, flinging his arms out to try and stop the man mountain. Commentator Graeme Hughes screamed into the microphone: “This will be incredible! Sironen! Charging! Chargingggggg! THEY WON’T STOP HIM! What a try! What a rugby league try in a grand final!”.

The length-of-the-field effort was Sironen’s sixth try of the season and one he’ll never forget.

“It seemed to happen in slow motion,” he recalls. “I was never big on support play but I just started jogging and running. I could see something happening. It was one of those things where you get a gut feeling for something. It just started unfolding in front of me. I thought ‘there’s something happening here ... hang on ... hang on’.

“Jimmy Grant got to the ball, he passed it to Currier and it all opened up for me. I hit the hole. In saying that, I wasn’t sure for a second because Brad Clyde was after me but then I knew I wasn’t going to get stopped. I was thinking ‘I’m going to score this bastard!’.

“That was me at full pace. I just had to pin the ears back. Scoring that try was one of the absolute highlights of my career.”

Hughes’ delirious description was possibly an understatement. With the Andy Currier conversion Balmain were suddenly ahead 12-2. For 40 minutes they had scrambled in defence to stay in the game, yet now they were well out in front. On the flipside, Canberra had looked certain to score on numerous occasions but were now10 points behind.

Behind the try line Meninga chipped Belcher for not getting to Currier’s kick in time. “F*** Badge, get the f***ing ball on the full!” But he then reassured his clan that things were under control.

“We were playing good footy,” Meninga recalls. “We were doing everything right. The bounce of the ball wasn’t favouring us. But we had great self-belief.

“I said to the boys that it was just a freakish bounce of the ball that had worked Balmain’s way. There was nothing we could do about it now so accept it and move on. We had to keep doing what we were doing. It was only two tries. For us that was no big deal.”

But, as the two teams trotted off, what Meninga didn’t know was that in 1989 Balmain had never given up a 10-point lead at halftime. And, in the history of NSWRL grand finals, no team had ever come back to win after being 10 points behind at the break.

The scene on the third floor of the Sydney Football Stadium Members Stand was like a modern day spaghetti western.

To get to the dressing rooms at halftime the Balmain and Canberra coaches had to take the elevator down to ground level

But as they stepped into the lift Tim Sheens and his assistant coach Phil Foster discovered they were in the same confined space as Warren Ryan and his coaching coordinator Brian Satterley.

Foster looked at Sheens, Sheens looked at Foster. Ryan looked at Satterley, Satterley looked at Ryan. Sheens looked at Ryan, Ryan looked at Sheens. There were plenty of eyeballs moving but no one spoke.

Then, just as the elevator arrived at their destination, Foster broke the silence. “We should be in front,” he said to Sheens. “We’ll get these blokes.”

And that started the eyeballs again. Left, right, straight, across, down, up. But soon the doors slid open and the men went their separate ways.

As the Canberra pair fell in with each other, Sheens asked Foster: “What the hell did you say that for?

Foster replied: “Well, it gives them something to think about, doesn’t it?”

Sheens shook his head and laughed and they headed off to see the players.

As Ryan walked into the Balmain rooms the place was buzzing. Everyone knew the team had been off their game yet they were leading by 10 points. Surely it could only get better.

“We’d struggled through the first half and you walk into the sheds thinking ‘s***, how the hell are we ahead by 10 points?’,” Paul Sironen recalls. “I remember shaking my head thinking ‘bloody hell’.

“We felt good. We’d had no field position, precious little ball in good attacking areas yet we were up by 10. So we’re thinking if the game swings our way and we get some ball in their area then we’re on track (to win a grand final).

“Blokes were talking, people were bubbling away. But as soon as Warren wanted everyone’s focus he got it.”

And Ryan wanted that focus to be on their second half strategy.

In the book Masters of the Game _ Coaches who shaped Rugby League by Tony Adams, Ryan says: “I remember saying to the players at the break ‘you’ve got a big enough lead to win two grand finals. But you’re lucky to be this far in front. You’re going to have to play a lot better’.”

Pearce recalls his coach’s half-time warning in his autobiography, Local Hero.

“Warren introduced exactly the right note at half time, emphasizing how quickly the situation could change,” he wrote. “That it could only take a couple of minutes for Canberra to score two tries. ‘Don’t relax, you mustn’t relax’, he said. He also warned us about Canberra’s outside backs, about their lethal weapons Meninga, Ferguson, Daley and Belcher. Warren knew we were in no way ‘safe’, and that was the point he pushed.”

Elias also recalls Ryan talking about the precious points they had on the board.

“He wanted us to protect that lead,” the hooker says. “He said ‘this is a good lead in a grand final, you don’t get them much better than this’.”

Across the corridor Sheens let the players relax, grab a drink and have some time to themselves. Meninga took this chance to speak with his coach.

“Sheensy, it’s okay,” the skipper said. “Everything’s good. We’re alright, we’re playing well, we’ll get there.”

Sheens nodded in agreement and then called the team together. He knew they had self-belief, but with a 10-point deficit hanging over them, he figured the troops needed a bit of reassurance.

“OK, Balmain have scored twice but both tries were totally against the run of play _ an intercept and a lucky bounce,” Sheens said. “Do you agree with me?”

The players said yes and nodded.

“And I definitely feel we’ve been the better side out there. Do you agree?”

Once again the coach got a positive response.

“OK, well keep believing in yourselves. Stick to the game plan and we’ll get there. Look around the room at how many quality players are sitting beside you. We have the ability to win this game. It may take 10 minutes, it may take 20 minutes. It may take until the last five minutes but we’ll get there.

“Forget about the score line. Go out there as if it’s nil-all and win this football match.”

Laurie Daley clearly remembers how positive his coach was at the halftime break.

“Tim said it might take until the 60th minute, or the 70th minute or even the last few minutes but we’ll get there,” Daley recalls. “We just had to believe in the game plan _ to use our backs and to keep kicking deep and turning Balmain around.”

After Sheens had finished speaking Meninga stepped up. The captain didn’t usually address his team-mates at halftime but he had something to share with his men. The message was positive, but it was also personal.

“Guys, we’ve got one half of footy to go,” he said. “Don’t leave anything in the tank. Don’t come back in here saying we should have done this or should have done that. This is our opportunity. Right here and now. We can do this.”

Watching on was replacement forward Steve Jackson. As he looked at the intensity in Meninga’s eyes and heard the power in his voice, the rookie Queenslander felt a shiver run over his skin. Earlier he had been happy to sit on the bench in his brand new jumper. But after listening to Meninga he just wanted to get out on the field and do anything he could to help his captain.

“I wish I had a tape recording of Mal’s halftime speech because I’d make a million dollars,” Jackson recalls 25 years later. “I don’t remember exactly what he said but I remember the feeling in the room. There was something he said that just left us all beaming. And it just oozed out of him and into us. Mal carries so much respect from his peers, he has real presence. Everyone was just silent. You could hear a pin drop. It was just special. It was a really special time.”

And so at 4:09pm the second half got under way. This time Canberra were running left-to-right with Balmain defending the southern, or Sydney Cricket Ground, end. Once again, there were no passengers out on the paddock as the game continued at a pulsating pace.

Then, at the 14th minute, Canberra were gifted their sixth penalty of the match. Bill Harrigan, refereeing his first premiership decider, made one of the most controversial calls in grand final history.

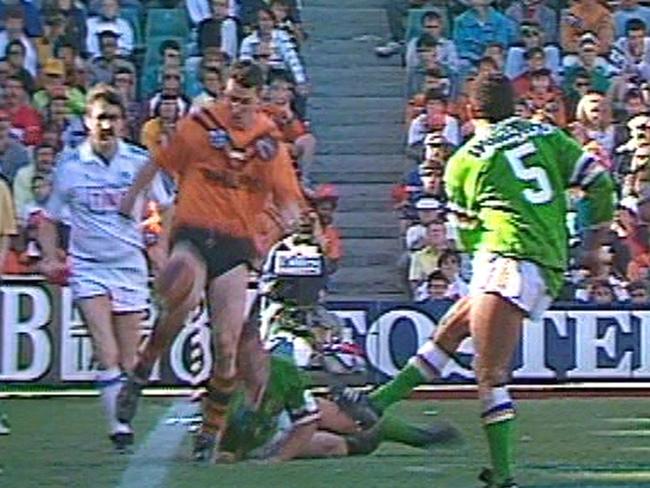

Balmain’s workaholic second-rower Bruce McGuire had made another charge forward near his own quarter line. As he got up to play the ball, there was no one in front of him. Instead of playing it backwards he tapped it forward, a decision that was within the rules. But as he started running, Canberra hooker Steve Walters came from behind McGuire _ from an offside position _ and appeared to obstruct him. McGuire then grabbed hold of Walters, using him as a barrier, which stopped Brent Todd and Bradley Clyde from tackling him.

Harrigan blew his whistle. He had two choices. He could either penalize Walters for being an obstruction when he’d come from an offside position. Or he would adjudicate against McGuire for using Walters as a shepherd so the two Canberra players _ Todd and Clyde _ couldn’t tackle him.

He flung his right arm Canberra’s way and ruled against McGuire.

The Balmain players screamed in anger at the whistleblower. Roach, Elias, McGuire and Pearce all remonstrated with Harrigan about his decision.

“I couldn’t believe it,” Pearce says 25 years on from a decision that still burns. “He obviously put his hand up the wrong way.

“I said ‘what’s that for?’, and he said ‘not in the spirit of the game’ and I said ‘what!?’. “He obviously meant to give us the penalty but he’s put his hand up the wrong way. Instead of swinging around with his hand in the air _ because he’s inexperienced and in his first grand final _ he’s actually kept his hand up in the direction of Canberra.

“Then he was mumbling, he stumbled around and paused for a second when I queried what it was, then I’m pretty sure he said that it wasn’t in the spirit of the game.”

When asked about the incident after the game Harrigan was adamant he’d made the right call.

“If Walters had touched him with the intention of interfering, McGuire would have got a penalty,” he said. “McGuire chose to stay behind Walters and use him as a decoy. Then as other Canberra players approached, he went to the other side, so they couldn’t get to him. Walters never intended to make the tackle, but McGuire went to his side and used him as an obstruction.”

Over the years it’s the question Harrigan gets asked about the most and he admits it might be time to look at the video again.

“On the field I was just reacting to what I saw,” he says 25 years later. “When I did it I thought it was all McGuire at fault using Walters (as a shepherd).

“(The continual speculation) makes me want to go back and have a look myself now.”

Watching the game up in the stands, Ryan was fuming. He vented his fury after the match, saying: “I will debate to the day I die that the penalty against McGuire was wrong. It should have been against Canberra.”

McGuire also had his say when grilled by journalists in the dressing room.

“Mate, he (Walters) wasn’t onside,” he said. “That changed the game. In past games I’ve run behind footballers who were running back while offside. I’ve never heard of it being an offence until now.”

The penalty proved prophetic. Just as Sheens and Meninga had predicted in the dressing room the ball _ at some stage _ would bounce their way. From the following set of six Gary Belcher finished off another backline raid to race over for Canberra’s first try. Finally the Tigers’ defence just couldn’t cope. When Meninga kicked the conversion the score was 12-8 with 23 minutes to go.

The next six minutes of the match will never be written in rugby league annuals. You won’t find them engraved on a trophy or printed on a pennant or written on a medal hanging from a string. But they’re the six minutes of athleticism and attitude that encapsulate why this grand final was so close to perfection.

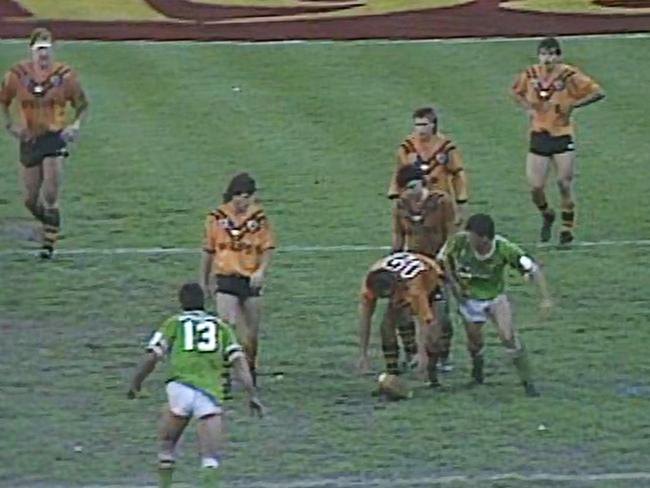

Balmain kicked off and for six sets of six tackles the ball never went out of play. Both sides believed in themselves and refused to lie down. Canberra halfback Ricky Stuart unleashed his lethal backline, firing 20-metre passes to the left and right of the field with Daley and Ferguson running wild. Then Balmain got the ball and returned fire, sending wave after wave of forward charges at the Canberra fortress. First McGuire, then Sironen, then Roach. On the next set of six, towering young prop Steve Edmed started the raids. A quick play-the-ball and Roach flung himself at the Canberra defence before Sironen unleashed his 115kg frame at full speed. Not to be outdone, the Raiders granite-like prop Glenn Lazarus started thundering into the Balmain defence like a bowling ball. After skittling two or three tacklers he’d jump up to play the ball with quick-fire speed giving Canberra another roll on.

The non-stop action went from one end of the field to the other and the pace of the game had 26 footballers panting as they tried everything in their power to either make a break or stop their opponents from breaking through.

“It was, without a doubt, the fastest game I’d played in up to that point,” admits Pearce.

Meninga agrees, saying: “It was the quickest club game I ever played in. It wasn’t much slower than it is today. It was up and down the field. The whole game was riddled with extraordinary efforts by both sides. It’s not often you see every player who took the field being prepared to have a go.”

As he sat up on the second floor of the Members Stand watching the action below, a name kept tapping away in the back of Tim Sheens’ mind. Finally he got on the walkie-talkie to his assistant coach, Phil Foster, who had stayed near the sideline with the bench players for the second half.

“Hey mate, I’m thinking about Steve Jackson,” Sheens said over the two-way. “What do you reckon?”

“Yep. Jacko’s your man, you gotta get Jacko out there,” Foster replied. “He’s down here pulling his hair out, he wants to rip in.”

At that moment Steve Jackson, who was sitting a couple of rows in front of Foster, thought he heard his name crackle over the walkie-talkie. Suddenly he could feel his heart pounding.

Sheens had an array of footballers sitting on his bench to choose from. Most of them were regular first grade players he had relied on many times before. In contrast, Jackson had started just one top level game in four years and only lasted 20 minutes in that match after injuring his knee. But Sheens believed the burly Queenslander could be his “super sub”.

“I had covered the bench with different scenarios,” Sheens recalls. “From guys who could do this and guys who could that depending on where we were in the game.

“At that moment my idea was to play attacking footy to win and that’s why Jackson got the nod. He had good leg speed, good size and the ability to break a tackle.

“I also wanted to maintain the speed around the ruck and I thought Jacko offered a bit more there.

“(At that stage) the game had slowed to the point where whoever you threw out there you didn’t need a worker you need someone with a bit of impact as well to make a difference.”

After a quick chat to Foster, Sheens told him to get Jackson ready.

“Jacko,” Foster yelled out. “Warm up.”

Jackson flew out of his seat so quickly he almost tore his hamstrings. But he was also wary.

“Back in those days you could go to the side of the field and the bloke you were supposed to be replacing would come good so you’d end up back on the bench,” Jackson remembers. “So I stood in the tunnel just doing a couple of pretend calf stretches.

“Then, a couple of minutes later, Phil looked over the edge of the tunnel and said ‘Jacko, you’re on for Todd’. When he said that my heart almost jumped out of my mouth.”

He sprinted out to the middle of the action. There was 17 minutes to go and Canberra were on the back foot. A scrum was being put down just 10 meters out from the Raiders line near the north-west corner. Jackson locked himself into the prop forward position and set himself to play the game of his life.

TOMORROW PART FOUR

An ankle tap, a field goal sensation and the winning play that wasn’t supposed to happen.

Originally published as 1989 Canberra v Balmain NRL grand final: how a penalty changed the game