Zach Tuohy reveals strained relationship with Brendon Bolton in his time at Carlton

The 2016 season had barely begun when Zach Tuohy knew things weren’t going to work out with his new coach. “I’ve never, ever dreaded going to work as much as I did when Brendon Bolton was in charge”. Tuohy opens up on his tumultuous final season at Carlton in his new book.

AFL

Don't miss out on the headlines from AFL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The Clarko disciples were hot on the market, and Carlton decided they needed one to turn it all around. On 24 August 2015, Brendon Bolton, who was an assistant to Clarko at Hawthorn, was announced as our new senior coach.

In the beginning, I was desperate to make it work. When you’re working on a relationship, of any kind, and I’ve never had to work so hard on a relationship as I did with Bolts, they say communicating is crucial. But communicating is difficult when your ‘partner’ doesn’t want to talk or isn’t very skilled at it.

I found Bolts very intense. It was difficult, in fact almost impossible, to have a casual chat with him about anything unrelated to football. On Monday morning, there was no weekend small talk.

‘Hey, Bolts, how’s things?’ you might say as you walked in the door.

He couldn’t respond with non-footy chat. It would immediately turn to the match we just played or the plan for the week ahead. And I would think, Jesus, mate, just say ‘hi’ back and leave it at that. Or make a gag and move on. I didn’t ask for a fucking deep and meaningful about where the club is at. He just couldn’t turn off for a second. I started trying to avoid him.

Now, if that’s what the attempted small talk was like, can you even imagine how meetings were? Let me help you.

The first match we played under Bolts was against his former team, Hawthorn, in the Community Series, as the pre-season competition was called back then. The match was in Launceston, and Bolts was keen to make an impression and set the tone for how match week and travel would work during his tenure. Little did we know it, but a minor decision on the plane would set the tone for the whole weekend – and perhaps the season.

When we took off from Melbourne, the flight attendants made their way down the aisle with the refreshments trolley, offering tea or coffee, and a biscuit. I had a coffee, skipped the biscuit and settled in. From memory, the biscuits were those little shortbread tasty morsels. Why do you need to know this? I can explain.

When we arrived at the hotel, we were called into the team room for a meeting. The gathering looked different to when Ratts or Mick was in charge. All the assistant coaches were in their team gear, even though we weren’t planning to leave the building. Bolts had directed them to wear full kit, as he wanted everything to feel formal. He wanted them and us to know that, even though it was a pre-season game, it was a serious work trip – we weren’t there to have fun. It became abundantly clear that there was no fun to be had as soon as we sat down.

‘I’d like any player who ate one of the biscuits offered to them on the plane to stand up.’

Now, at this point I’m thinking, Is this a joke? Surely, it’s a joke. But his tone was serious. Players started to stand up. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. Mostly I couldn’t believe I wasn’t one of the ones forced to stand up. It wasn’t like me to miss the opportunity of a biscuit. Maybe I hadn’t been feeling well.

I was still thinking that this must be some sort of ice-breaker, or a prank.

‘Do you think it’s professional to do that? Is that going to make you a better player?’ Bolts demanded.

F.ck me, it’s a biscuit, I thought. A lot of players were standing up.

I couldn’t believe what I was seeing and hearing. I got that the guy wanted to set the tone and the standard, but this shit was crazy. It was officially ‘Biscuit-gate’.

We lost by 21 points. But all I remember is the shortbread. That incident stayed with me throughout my career. I can’t get on a plane, even for a holiday, without thinking about it when I see the trolley.

When we got into the regular season, the level of intensity at meetings made Biscuit-gate look light-hearted.

Round 2 should have been memorable because, when we took on the Sydney Swans at Etihad Stadium, I was playing my 100th game, and my parents had travelled over to watch. But we had lost to Richmond by 9 points in Round 1, and in my milestone match the Swans thumped us by 60.

Back-to-back losses doesn’t make for a very celebratory occasion. Which is a shame. When I first joined the club, Setanta Ó hAilpin talked to me about what an honour it would be, as an Irish player, to make it to 100 games. Here I was, with a hundred matches under my belt, but no one was in the mood to talk about it, including me.

At Carlton, it seemed things could always get worse, and they did.

We lost to the Gold Coast Suns by 54 points at Metricon Stadium in Round 3. When we assembled for the match review, the atmosphere was tense. On the occasion of a particularly rough review, assistant coach John Barker would say to us on the way into the meeting room, ‘Put your seatbelts on.’ This was his way of lightening the mood, while warning us that we needed to be ready for some direct feedback.

Despite the loss, Sam Docherty had shot the lights out. As we all knew, he was such an elite player, and he had played an unbelievable game, even by his lofty standards. Sam isn’t just one of the best footballers I’ve played with, he’s also one of the best people. Inspired by his epic performance, Bolts decided that the mantra for the meeting would be: ‘What would Doch do?’

In theory, this sounds good, right?

A superstar of the club getting the acknowledgement he deserved for a good performance in a loss. I mean, it’s easy to play well when you’re thrashing a team, but to keep your standards high in a loss is impressive.

Bolts ran through every aspect of our game, and after each one, he would more or less ask, ‘Why can’t you all play like Sam?’

The meeting consisted of a series of highlights of Sam’s (there were plenty to choose from), followed by a lowlight from one of his teammates.

At one point in the meeting, Bolts drew our attention to a video that highlighted what he perceived to be a lowlight. It involved not only me, but Sam too. Perfect for this meeting, very on-brand, I thought.

I was in a stoppage, and the ball was bouncing around but I managed to gain possession. Doch had run around on the outside, and I went to give it to him, but a Gold Coast player – Aaron Hall, I think – dove to intercept, so I quickly changed course and kicked it forward. A different Gold Coast player intercepted – I had caused a turnover. I thought nothing of it during the match, because I thought I had taken the only safe option, even though it didn’t work out. It turned out Bolts had not dismissed it so easily.

‘Why didn’t you pass the ball to Doch?’ he asked.

I just wanted this part of the meeting to be over, so I responded quickly, and in a way I thought he’d be pleased with, and therefore move on from. ‘Actually, looking at it now, I should have tried to squeeze it through to him, as he’s made such a good run,’ I said. ‘I wanted to give it to him, but I thought the Gold Coast player had read it and would intercept if I tried to squeeze it through, so I just reacted to that and tried to kick it forward.’

I thought this response was satisfactory, but Bolts wasn’t having any of it. He continued to pursue it. Johnny Barker was trying to interrupt to defend me, but Bolts wouldn’t let him speak.

He was fuming. It wasn’t enough that he was talking me down. He decided to open it up to the group. He started asking my teammates what they thought, including a player who was a hero of mine back then (and I still think the world of him).

‘What do you reckon?’ he said to Kade Simpson.

‘It’s tough, but yes, he should just give it next time,’ Simmo responded.

Simmo really should have told him that, no, he was wrong. But he probably wanted this ordeal to be over just as much as I did. I don’t blame him. No one was going to stick up for me. As we watched my alleged misdemeanour in super-slow motion and I pointed out that I only had a millisecond to make the decision, it all fell on deaf ears.

I’m not opposed to this sort of post-mortem after a loss. This is the stuff that good teams talk about all the time. But there’s a constructive way to do it. For example, a coach could instruct you that, next time, you should give that handball, even if there’s an element of risk. The coach could explain that if they end up turning it over and they score a goal, we’ll cop it, because we know that for every goal they kick, we’ll kick five because we’re giving those handballs.

If he’d said something like that, I would have been like, ‘Okay, that’s what we’re doing from now on.’ And I’d have followed that instruction to the letter.

But there was nothing constructive about that meeting. A Doch highlight, then a lowlight. Then the pivotal question.

‘Doch wouldn’t do this, so why did you?’ Over and over.

Sam was sitting near me. He was mortified by the whole process. He’d had no idea this was going to happen before the meeting started. He looked like he needed a seatbelt for different reasons, as he was squirming in his seat so much it could have caused an injury.

If Doch wasn’t so loved by his teammates, this could have been a really good way to divide the team. If he wasn’t everyone’s favourite teammate, he might have been completely isolated from the group. But his character, and popularity, meant this meeting didn’t result in that worst-case scenario.

I was furious. I’ve never been so angry after a meeting. It was Round 3, and I officially knew: Bolts wasn’t into me.

I’ve copped sprays from coaches over the journey – senior coaches, assistant coaches, VFL coaches – they’ve all had a go and it’s never felt personal. This was the only time in my fifteen-year career that I’ve sat in a meeting and thought, ‘This bloke just has it in for me’.

My approach from that day onwards was to just try to get through the year. I couldn’t help but think about the irony of our pre-season chat when I mentioned him asking what the club needed to do to be better, and I suggested that we start with not being so f..king miserable?

I can confirm that I’ve never, ever dreaded going to work as much as I did when Brendon Bolton was in charge of the club.

The only thing worse than a group meeting with Bolts was a one-on-one meeting. And Bolts loved to line up meetings.

On one occasion, he set up a get-together which involved a senior player and one of the younger players going into his office to look through video clips of games. I was paired up with Jacob Weitering for one of these meetings. We looked at some of his plays, and they were largely positive, with Bolts offering a few coaching notes.

Bolts was actually a great coach, but his communication style was lacking. At the end of the meeting, he turned away from Jacob and looked at me.

‘Do you have any feedback for me as a coach?’ Bolts enquired. That was when I made a fatal mistake. You see, I assumed that when he asked me for feedback, he wanted … well, feed- back. In reality, what he wanted was to be told how fantastic he was. Unfortunately, I had misinterpreted the question and instead I responded with real feedback.

‘Things are going great, but I do get the impression that some of the younger players are intimidated by you. I don’t feel like they’re comfortable speaking to you,’ I offered politely.

Silence. And then some more of it. Silence is awkward.

I spoke up. I needed it to end.

‘As I said, things are really great, I just don’t think many of the younger blokes would be willing to knock on your door for a chat if it wasn’t an organised thing … like this.’

He. Was. Fuming.

I knew it when I left the office, but confirmation quickly followed.

An hour later, John Barker approached me. ‘What did you say to Bolts? Because he is filthy with you. He’s in his office, chewing his lips off.’

Oh no, I really had interpreted his question wrongly. Things weren’t good between us, obviously, and my feedback wasn’t going to help.

A week later, Bolts was clearly still overthinking our interaction, so he brought it up in a team meeting in what he thought was a positive way. To me it felt so staged. I still don’t know if he was trying to make me feel better or make himself look good.

‘So, I asked Zach for feedback in a meeting, and he gave me feedback that I wasn’t ready for at the time. I didn’t want to hear it, but now I’ve processed it, and it was good feedback to hear.’

At the time, I was thinking, I can’t read the guy at all. Is it all for show or does he mean this?

While he seemed to be trying to make the point that he was over it, it didn’t feel that way. He was frosty with me, at best, but sometimes under pressure things would really blow up.

One of those times was during a half-time meeting at Etihad Stadium, when we were losing. We lost a lot that year so it’s difficult to remember which particular beating this was, but I was sitting in my usual spot when he yelled at me. I had entered the room to find my seat in the back corner, furthest away from the door. That’s where I always sit in meetings and continued to do so until the end of my career. I was sitting next to one of our assistants, who was talking second-half tactics. But Bolts had started his half-time speech and I hadn’t realised, because I was bending down to tie my laces

‘Zach, look at me when I’m talking to you,’ he bellowed.

That was the teacher in him.

Alright, Dad, calm down, I thought. I’m not five years old.

I did not say the above. Luckily. He was red with anger; things had the potential to escalate further if I responded at all.

I knew my place. As a running half-back I was third fiddle behind Doch and Kade Simpson. He adored Doch, who was captain, and Simmo was a club legend, and then there was me, who he didn’t even like. The problem was I was increasingly getting the feeling that Bolts didn’t even consider me worthy of playing third fiddle.

Things were bleak, which was ironic, as the phrase Bolts loved to use to summarise our approach to the season was ‘blue skies’.

All AFL clubs decide on a mantra at the start of the year. They have a meeting and talk about their objectives and goals for the season and come up with a phrase that best represents that. One of our 2016 catch-cries was ‘blue skies’. Which I think was meant to signify clarity of mind and good decision-making etc. Bolts, being the intense bloke he is, really took this seriously. He had a meeting with the whole club to decide it. Everyone from the team doctor to the head of membership was there. I’m not sure if the team doctor at the time, whose only focus was keeping us healthy, was sure why he had been included. But ‘blue skies’ is what emerged, and it was used repetitively at all club meetings.

The famous catchphrase even started to creep into Bolts’s media interviews. I cringed every time I saw it in print. After I left, the phrase was ‘green shoots’, and you might recall how,

when Bolts went down the slide at ‘The Big Freeze’, he brought a watering can and said, ‘I’ve just got to keep watering those green shoots at the Blues.’ He was obsessive like that. Another example of how he couldn’t switch off.

At the end of the season, which wasn’t a good one – we finished fourteenth on the ladder with a 7–15 win–loss ratio – I knew things between me and Bolts had gone absolutely tits-up. I was out of contract when I went to a meeting with him and Neil Craig. Neil was the director of coaching, development and performance at the time, and I was a big fan of his. They wanted to know why I hadn’t signed my contract extension. I assured them I didn’t want to leave; I just wasn’t happy with the particulars of my contract.

During the course of this meeting, Neil complimented me. ‘I notice you’ve got better at receiving feedback, which is great.’

‘Oh, really?’ I responded.

I always thought I was quite good at that but obviously Bolts did not see it as one of my strong points.

‘For example, remember that meeting during the year when you kept biting back at Bolts?’

Oh. My. God, I thought. He’s bringing up the Doch meeting again. Were they trying to rile me up? Were they testing me again? And then there was the irony of Bolts overthinking my feedback that he didn’t like, for a whole week, so much so that he made the next team meeting about it.

I didn’t want to leave the Blues; I had been happy there until this year. But how could Bolts and I move forward if this was how it was going to be?

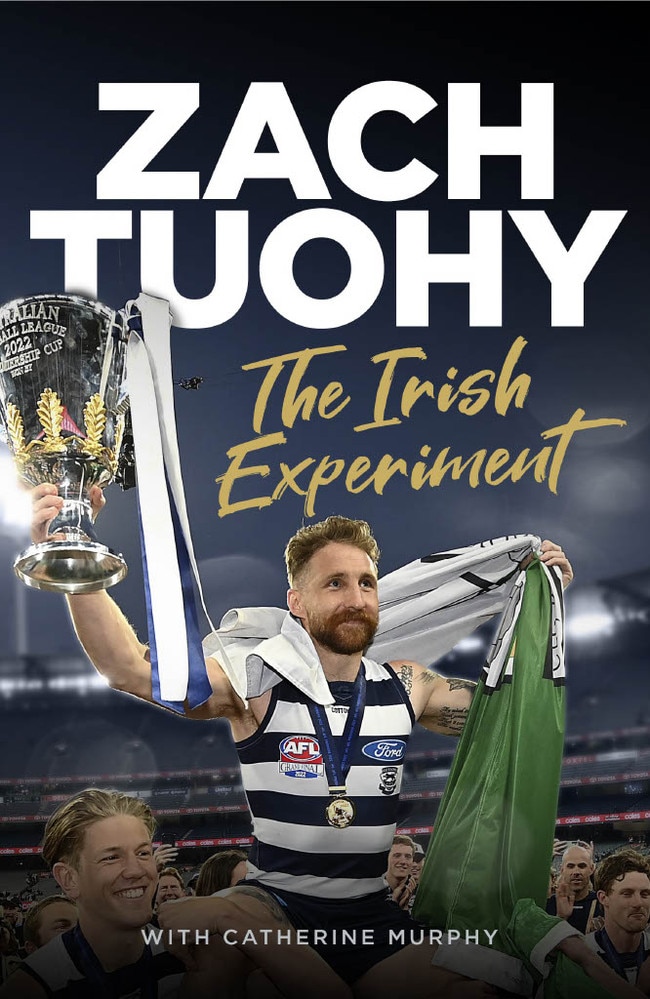

Zach Tuohy, The Irish Experiment is published by Affirm Press and is on sale from Friday

Originally published as Zach Tuohy reveals strained relationship with Brendon Bolton in his time at Carlton